The Monday Extract: Dutch émigré artist Theo Schoon was an anti-Semite and a shithead in so many ways, but he was also a brilliant artist who recognised the beauty and power of Māori art at a time when few Pākehā gave it a second thought. His biographer Damian Skinner reckons with a ghastly genius.

In the summer of 1966, Janet Frame and psychologist John Money caught a bus to the Grey Lynn home of Dutch artist Theo Schoon. Money had long financially supported the artist by buying artworks whenever he could afford it, just as he did with Rita Angus, another artist he believed to be a genius; and just as he had supported Janet Frame. But Schoon hadn’t replied to any of his recent letters, and he wasn’t answering the phone, so Money and Frame had decided to investigate. They found the house at 12 Home Street abandoned, no sign of Schoon. They concluded that he must have moved out.

Schoon had been living at the small weatherboard cottage, set slightly below street level, ever since another old friend had bought it for him to live in for as long as he wanted. Schoon quickly put down roots there – seeking out and then planting seeds for the gourds that had become so important to him. He lived surrounded by an extraordinary creative mess, and entertained a steady stream of guests, typically those who could put up with his idiosyncratic housekeeping. Always concerned with the conditions in which his precious gourd plants grew, Schoon would encourage visitors to use a bucket in the bathroom so their waste could be added to the soil, rather than flushed down the toilet and wasted.

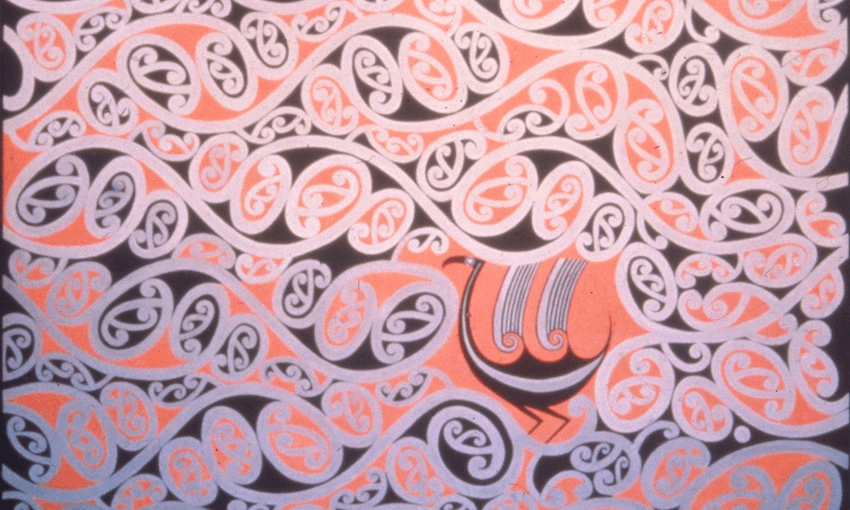

Home Street filled up with artworks. Painted panels with designs based on kōwhaiwhai (rafter patterns) and tā moko (tattoo) were stacked against the walls. Drying gourds in various states, from newly harvested to fully carved, sat in rows on the floor. Tea chests were filled with photographic negatives featuring a dizzying variety of subjects: Māori rock drawings from the South Island, close-ups of Rotorua mud pools, Māori art from museums and marae, and his own artistic experiments.

The house also filled up with other treasures, such as manuscripts for talks and articles – about Māori art mostly – and drafts of letters for the endless stream of correspondence that flowed out of Home Street to New Zealand and the world. There were clippings of newspaper and magazine articles, many written by Schoon in his role as cultural advocate for the overlooked and underappreciated, and some written about him.

The texts, images, artworks and conversations that filled this messy and modest home related to many of the most important developments in New Zealand culture and art, matters that continue to reverberate today.

Schoon was never very settled, and while Home Street was his base for a decade, he actively entertained the idea of leaving – not just Auckland, but New Zealand. By the time of Money and Frame’s visit, he had in fact decided he couldn’t wait any longer. The most likely catalyst was his Auckland exhibition at the New Vision Gallery in April 1965. The show was a big deal, a large financial and emotional investment in artworks that he imagined would showcase the contribution he had made to modern art in New Zealand, and cement his place as a visionary and pioneer. It was by no means a failure. It received positive coverage in the Auckland press, and the newspaper art critics were warmly receptive.

But the work didn’t sell, and it didn’t have an immediate impact on New Zealand art. Schoon’s magnificent visual demonstration of what might result from the encounter of Māori and Pākehā art remained interesting to those who already knew about it, and no more important than the many other ways to be a modern artist in New Zealand for those who felt otherwise. Fed up, Schoon left Auckland and moved to Rotorua, in what was to be a brief stopover among the geothermal wonders he loved before his long-intended departure for North America.

When they arrived at Home Street, Money and Frame found the veranda totally overgrown with gourd vines. Inside, the house was filled with years of accumulated rubbish, bags of clay and drawing materials. Under the house Money spotted some of Schoon’s notebooks, photographs and albums, and art books. With the artist apparently gone, Money worried about what would happen to these abandoned treasures. There were also some plaster casts of the feet and hands of antique statues, the kind that art schools used to teach life drawing. Frame was quite keen to take them home, but had no bags to carry them in. Gathering together what they could easily transport on the bus, Money and Frame left the property. John Money was not to see Schoon again, but he held on to the items he had rescued, carefully storing them in his house in Baltimore.

In the chaos of Schoon’s decision to abandon his house and leave Auckland, much more had been lost from Home Street than Money could have known. A few months before Money and Frame stopped by, the house’s owner, Martin Pharazyn, had received a letter from Schoon declaring his deep unhappiness and his intention to leave Auckland. Concerned about his friend, Pharazyn travelled to Auckland in his Kombi van and helped Schoon pack up 12 cases of personal possessions, which were to be stored at the North Shore home of Schoon’s old friends Bob and Ellen Boot. When Pharazyn returned to the house a week later, he found the cases gone. Assuming that Schoon had finished moving and taken everything valuable from the house, he contracted some men to clear out and burn the rubbish left behind. He also rang John Parry, head of the art department at the city’s Seddon Memorial Technical College, and asked him if he would like to take the clay and unused drawing materials for his students.

When Parry arrived at Home Street, he found three men burning Schoon’s paintings, prints and drawings on a large bonfire in the back yard. It turned out that Schoon and another friend had packed up the rest of his artworks and stored them under the house, ready to be shipped to Rotorua; these, the men had decided, should be the first things to be burned in the clean-up. Parry rushed outside, explained who he was, and asked if he could have the artworks to show his students. The men agreed, and the artworks were taken to the school art department. But they didn’t escape the fire for long. Shortly afterwards, the prefab building in which they were stored burned down, and they were all lost.

Fernyhough collection.)

Theodorus Johannes Schoon (1915–85) was a pioneering artistic polymath, a painter, printmaker, photographer, gourd and jade carver, and ceramicist. He was a Dutchman, born and raised in Indonesia, who became a Pākehā in cultural outlook, and also despised the ignorance of New Zealanders and the provincial version of British society he ended up in for most of his life. He was a migrant who lived in Indonesia, Europe, New Zealand and Australia, and who used his sense of difference and being out-of-place to see in new ways, especially when it came to Māori art. He was a bohemian who refused to live a conventional life in mid-twentieth century New Zealand, flaunting his exoticness through his clothes, his living environments, and his elegant gestures and movements. He was a gay man who didn’t like women, and who had intense and difficult relationships with gay and straight men, and few romantic or sexual partners. He was a charismatic teacher and mentor, and entirely convinced of his artistic superiority, demanding that other artists take on the student role, even if they were older and more experienced than he was. His artistic and cultural interests have infiltrated our cultural and visual consciousness, shaping the look of contemporary New Zealand.

Later in life, when Schoon would summarise his personal history for new acquaintances, his early years in Java were always foremost in his mind. He might say, for example, that he was born of Dutch parents in Indonesia, and trained as an artist in Europe before returning to Java where he worked as a portrait painter, especially of court dancers and the concubines of the local Rajahs. He would emphasise his abilities as a Javanese dancer — skills he learned alongside the princes who were his schoolmates. He might talk about visiting Bali, where he also painted portraits of dancers, and met some of the celebrities who were visiting the island in the 1930s.

But then Schoon’s narrative would turn dark, become a tragedy. The Second World War broke out, and he found himself marooned in New Zealand – not just for the duration but, as it turned out, for decades, since the Dutch East Indies achieved independence and became Indonesia, and his white skin and Dutch name made him a target for any Indonesians who resented colonialism and wanted to express it. He was not able to return to the place he loved best.

Years after he came to New Zealand in 1939, Schoon continued to describe his residence in this country as a kind of exile. It was made bearable only by his chance encounter with Māori art, which grew into an obsession and prevented him from leaving. In Māori art and culture Schoon found objects and ideas and social patterns that evoked what he had left behind in Indonesia. And it was his childhood and early twenties in Java and Bali that explained his ability to see things that other Pākehā could not, and to be open to cultural difference in a way that was unusual in Pākehā society in the 1940s.

Schoon claimed to feel out of step with European culture. “I have nothing in common with the white New Zealand culture, which is Victorian and dead,” he told one correspondent. “But the Maori culture, decadent as it may be, still has colour, flavour, and that irrationality which never fails to baffle, astonish, and fascinate me.” Prepared by a childhood in Indonesia, and the voracious appetite that art students in Europe had for what, in the 1930s, was called “primitive art”, Schoon was ready for the encounter when it came.

Schoon’s life intersects with an impressive number of important people, periods and places. He knew many of the people who shaped New Zealand culture in the twentieth century. After he arrived in Christchurch, the Bloomsbury of the south, in 1939, he met and socialised with painters Rita Angus and Leo Bensemann, Betty Curnow and her husband, the poet Allen Curnow. In 1942 he moved to Wellington and became part of the flourishing creative scene that grew up around European émigrés who had fled the menace of Nazi Germany. He became friends with artists Gordon Walters and Dennis Turner and, during a later stint in the city, the poets James K Baxter and Louis Johnson. His three years documenting the Māori rock drawings in South Canterbury from 1946 brought him into contact with anthropologist Roger Duff and poet ARD Fairburn, while Gordon Walters and John Money both stayed with him in this limestone landscape.

collection)

Schoon was in Auckland in the 1950s and 1960s when the centre of the New Zealand art world moved north from Christchurch. He befriended potters Len Castle and Barry Brickell, and spent time with the painter Colin McCahon. His fascination with Māori art, and gourd growing and carving, led him to Māori carver Pine Taiapa, and then into the orbit of Māori artists like Paratene Matchitt, while connecting him to the Pākehā curators and academics, including Margaret Orbell, who were researching and writing about Māori art during this period. Later, his work as a jade carver took him to the West Coast, where he had contact with the carver Peter Hughson and others.

His artistic interests were extraordinary and extraordinarily varied, roaming across fine art and craft; Māori, Pākehā and Indonesian art and culture; into the landscapes of South Canterbury for the Māori rock drawings and the geothermal region of the central North Island for mud pools; and even into the confines of the Avondale Mental Hospital, where he encountered an artistic patient called Rolfe Hattaway. Many of these obsessions were decisive for other artists as well. And his example as an academically trained artist with a good knowledge of modern European art, and the commitment to do whatever it took to pursue his artistic projects, was both an inspiring and cautionary tale to those around him.

Schoon’s life was also an ongoing struggle. It’s a story of devil-may-care courage in the face of conservative and provincial values, of bad luck and carelessness, poverty, a willingness to live in miserable conditions in order to pursue his artistic interests, and of extraordinary charm and generosity mixed with intolerance and sometimes cruelty towards those who disappointed him, or who didn’t share his beliefs about the best antidote for the ignorance and conservatism of New Zealand culture. He died in Australia, having turned his back twice on the country he grew to despise.

An edited extract from Theo Schoon: A Biography by Damian Skinner (Massey University Press, $60), available from Unity Books.