The only published and available best-selling indie book chart in New Zealand is the top 10 sales list recorded every week at Unity Books’ stores in High St, Auckland, and Willis St, Wellington.

First, a quick PSA: Unity Books has a flash new website that lets you search and purchase from both Unity Books Auckland and Wellington – and the search function is impeccable!

AUCKLAND

1 Lioness by Emily Perkins (Bloomsbury Circus, $25)

Roaring back into number one for the second week in a row is the story of Therese and her midlife reckoning.

2 Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck (Granta, $28)

The international Booker Prize winner 2024.

3 Long Island by Colm Tóibín (Picador, $38)

The sequel to Brooklyn from an author who once said he’d never write a sequel. We’re delighted that he has.

4 Prophet Song by Paul Lynch (One World Publications, $25)

The Booker Prize winner 2024.

5 Before the Coffee Gets Cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi (Picador, $25)

Time travel with a tick tocking mug of coffee.

6 Blue Sisters by Coco Mellors (Fourth Estate, $38)

From one five-star review on GoodReads: “This was such an incredible book wowowowoww. Can not stop crying. The author is so good at taking you into the characters’ world and showing their feelings and thoughts and story like WOWWWW. I seriously feel connected to all of these characters in some way, little aspects about them were huge aspects about me. The writing is also brilliant and the prose is so perfect to me. I’ll be thinking about this book for a long time.”

7 All Fours by Miranda July (Canongate, $37)

From a New Yorker profile on Miranda July: “’If a book is really working, you’re in a narrow channel, and the water is going really fast,’ the writer George Saunders, a friend of July’s, told me. That is what reading “All Fours” is like: being swept, paddleless, down a coursing river, submitting to the thrill of the rapids. July’s narrator is ecstatically trapped by a plot that she has no choice but to set in motion, even as it upends her life. July knows how this feels. When a character serves as an alter ego for her author, it is natural to wonder if the things that befall her are taken from reality. But what of the reverse? When you mold an avatar in your own image, then send her on bold and outrageous adventures, you may find that you have opened a portal from the invented world into the real one — that what you have dared to imagine on the page may enlarge your imagination for what can happen beyond it.”

8 James by Percival Everett (Mantle, $38)

From the Guardian: “Percival Everett’s new novel lures the reader in with the brilliant simplicity of its central conceit. James is the retelling of Mark Twain’s 1884 classic, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, from the point of view of Jim, the runaway slave who joins Huck on his journey down the Mississippi river.

While it would be possible to enjoy James without knowing the original, its power derives from its engagement with Twain’s book. For British readers, it also helps to know something about the centrality of Huckleberry Finn in American literature – and African American discomfort with that centrality.”

9 Table for Two by Amor Towles (Random House, $38)

“Towles sometimes lays on the philosophical wisdom and historical knowledge a bit, but the novella and all the stories are treated to his understated (and occasionally mischievous) irony. A sneakily entertaining assortment of tales.” Read more at Kirkus Reviews.

10 Question 7 by Richard Flanagan (Knopf $40)

One of Australia’s most acclaimed writers might well have written his best book yet. Here’s the publisher’s blurb:

“Beginning at a love hotel by Japan’s Inland Sea and ending by a river in Tasmania, Question 7 is about the choices we make about love and the chain reaction that follows.

By way of H. G. Wells and Rebecca West’s affair through 1930s nuclear physics to Flanagan’s father working as a slave labourer near Hiroshima when the atom bomb is dropped, this genre-defying daisy chain of events reaches fission when Flanagan as a young man finds himself trapped in a rapid on a wild river not knowing if he is to live or to die.

At once a love song to his island home and to his parents, this hypnotic melding of dream, history, literature, place and memory is about how reality is never made by realists and how our lives so often arise out of the stories of others and the stories we invent about ourselves.”

WELLINGTON

1 Blue Sisters by Coco Mellors (Fourth Estate, $38)

2 Lioness by Emily Perkins (Bloomsbury, $25)

3 Long Island by Colm Tóibín (Picador, $38)

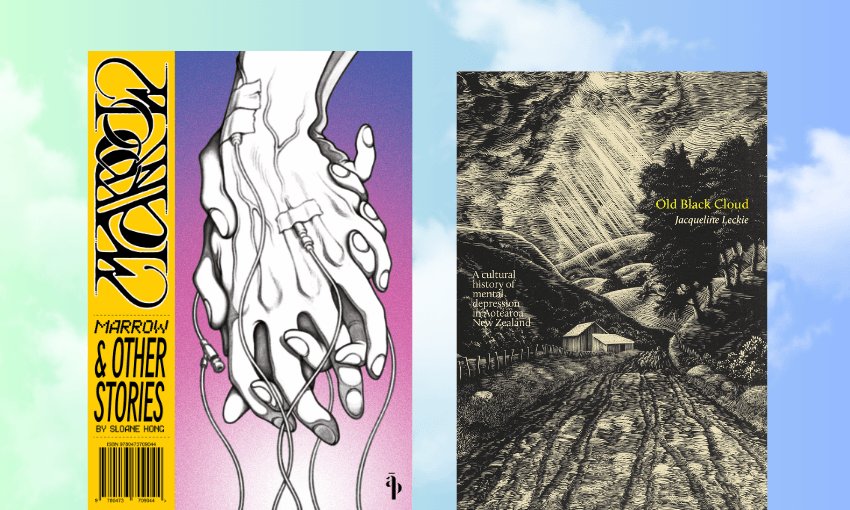

4 Marrow & Other Stories by Sloane Hong (Aporo Press, $35)

A beautifully produced collection of comics by Korean tauiwi artist Sloane Hong, and published by indie publisher of Spoiled Fruit, Āporo Press. Here’s the blurb: “Although varied in content, each story explores how we relate to each other and the world around us—through grief, love and our innate curiosity of the unknown. Plagued with intrigue and often unsettling, these gloriously stylish panels peel back layers of the human psyche, exposing them, throbbing and pulsating, for all to see.”

5 Old Black Cloud: A Cultural History of Mental Depression in Aotearoa NZ by Jacqueline Leckie (Massey University Press, $50)

The first cultural history of mental depression in Aotearoa is a well-researched, beautifully written exploration of depression across different cultures, at different times. Here’s the publisher’s blurb: “Mental depression is a serious issue in contemporary New Zealand, and it has an increasingly high profile. But during our history, depression has often been hidden under a long black cloud of denial that we have not always lived up to the Kiwi ideal of being pragmatic and have not always coped.

Using historic patient records as a starting place, and informed by her own experience of depression, academic Jacqueline Leckie’s timely social history of depression in Aotearoa analyses its medical, cultural and social contexts through an historical lens. From detailing its links to melancholia and explaining its expression within Indigenous and migrant communities, this engrossing book interrogates how depression was medicalised and has been treated, and how New Zealanders have lived with it.”

6 Energy: Get It. Guard It. Give It. by Lisa O’Neill (Major Street Publishing, $38)

“Author, leadership mentor and sought-after speaker Lisa O’Neill has been called a ‘Human Berocca’!” Find out more on the publisher’s website.

7 The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism (& How It Came to Control Your Life) by George Monbiot (Allen Lane, $39)

Do you know what neoliberalism is? Either way, this book is for you.

8 The Financial Colonisation of Aotearoa by Catherine Comyn (Economic & Social Research Aotearoa, $30)

One of the most recurrent books on this here list: a groundbreaking, revelatory piece of research that you can read about in this interview on The Spinoff.

9 All Fours by Miranda July (Canongate, $37)

10 Economic Possibilities of Decolonisation by Matthew Scobie & Anna Struman (Bridget Williams Books, $18)

Best purchased along with item 8 on this list.