After the announcement that Amazon is closing Book Depository, Shanti Mathias talks to publishers and booksellers wondering what will step into that void.

When you opened the package, a bookmark would fall out. It was colourful – a spin on a book cover, perhaps, or a cute illustration of people reading. And as you welcomed that new book into your home, to be read or loaned or simply to adorn your shelf, there were probably hundreds of people around the country checking their letterboxes and finding the same. A dispatch from Book Depository of a book they wanted, for cheaper than they could get it anywhere else and – crucially – shipped for free.

“New Zealanders are awesome readers, we love to read local and international literature, but not every book is distributed in Australia and New Zealand,” says Claire Murdoch, publisher at Penguin Random House New Zealand, speaking in her role as a member of the Publishers Association of New Zealand (PANZ) council. Affordable international literature – as well as those cute bookmarks – was another reason for New Zealand’s love affair with Book Depository.

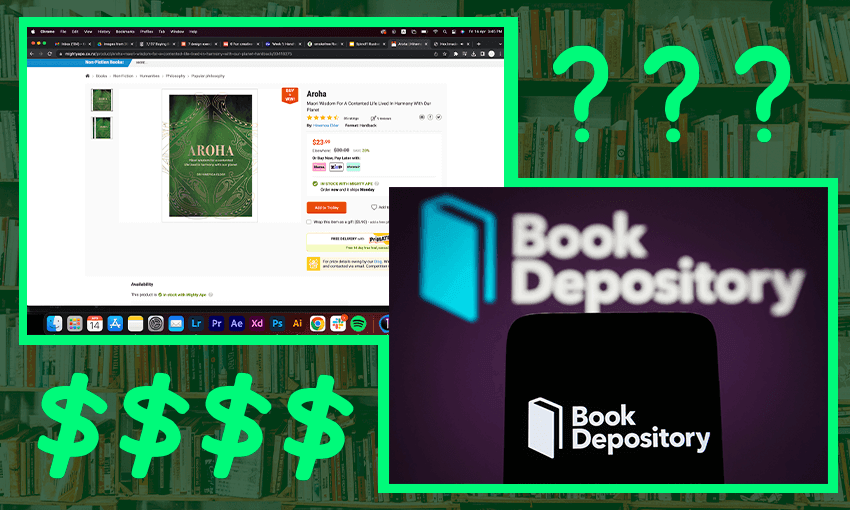

But the days of Book Depository, its ubiquitous bookmarks and alluring free shipping are now gone. Amazon, which bought the UK-based online retailer in 2011, announced this month that they’re closing the store on April 26. Thousands of book lovers will have to find somewhere else to shop. Is that good news for New Zealand booksellers?

“I think it is, actually,” says Tony Moores, owner of Poppies, a franchise with bookshops in Howick, Hamilton and New Plymouth. That said, he knows that “a lot of people don’t mind where they get the book from, they just want it.”

There are several reasons books might not be available in New Zealand, and which made Book Depository such an attractive option, says Murdoch. One is territorial copyright: authors don’t always sell, and publishers don’t always buy, global distribution rights, meaning a book published by a small publisher in the UK may have no-one who can distribute it in New Zealand.

The other is low demand. For a specialised engineering textbook, say, not assigned in any university but relevant to perhaps three people in New Zealand, there is no incentive for a publisher to distribute, or a bookshop to stock that book. “You need a warehouse and a sales team – there needs to be enough interest in that list,” Murdoch says. In some cases, bookshops can order these books for their customers, although they can take weeks to arrive from overseas. In other cases, especially with books in non-English languages, bookshops may not have relationships with the suppliers to get that book.

A lot of people buy a lot of things from Book Depository, but the site particularly focused on a “long tail” strategy, keeping small numbers of stock of books that weren’t particularly popular with the certainty that there would be people to buy them among their global customer base. The obvious people who are going to be most affected are people whose interest in books diverges from what is available in their country: people in countries like New Zealand who want books in Vietnamese or Spanish, and vice versa – people in Argentina or Vietnam who want books in English. People trying to buy self-published books from overseas will also be affected. “The free shipping made getting those books more economically viable,” says Murdoch.

Without Book Depository, the obvious large retailer with decades of experience in bookselling is Amazon, but without a local branch, the shipping can be expensive. For book sellers like Moores, the end of Book Depository is a reminder that despite Amazon beginning as a bookshop, the company isn’t really focused on readers (or, for that matter, publishers and writers). “Amazon makes much more money selling other things – book pricing is relatively constrained,” Moores says.

While Book Depository was owned by Amazon, their exclusive focus on books, as well as effective branding – your eyes falling on their logo-enhanced bookmark every time you opened the book – helped them to project a sense that they were a shop for readers. With the promise of free shipping, those readers just kept coming back.

The company hasn’t given a reason for their closure, but the free shipping was probably its weak point, as well as the wider tech downturn. Sending physical objects around the world is expensive. “It’s not economical or ethical – in terms of the carbon it burns – to send single books around the world,” Moores says. Three years of Covid has disrupted supply chains and freight systems. Pair that with inflation and high cost of living around the world, and suddenly the slim margins that Book Depository operated on became unprofitable to Amazon while the company is making other cuts.

Online retailers with similar models to Book Depository, making lots of books from overseas available, may also fill the gap. In New Zealand, this includes Mighty Ape, Fishpond and Booktopia – all of whom charge for shipping. Other alternatives are Blackwells, which has free international shipping (for now), Abe Books, and Better World Books, which includes former library books.

“I don’t know Mighty Ape’s market share, but they sell a lot of products – not just books,” Moores says. However, these providers will largely be ordering books from the same sources as local bookshops, so the price difference won’t be major. “When we order books for customers [from overseas], we’d rather have the sale than a big profit, so we often only charge a small handling fee and hope the customer will come back,” Moores says.

It’s also an opportunity for New Zealand publishers to acquire more international rights – and for publishers overseas to pay closer attention to New Zealand’s thriving books industry, Murdoch says. “Rights deals go both ways – this is potentially a moment for increased outward rights sales and outward book exports. New Zealander publishers may have more of an incentive to bring internationally published books to New Zealand, too, if people aren’t going to go and buy them on Book Depository.”

And while some people will migrate to other online retailers, and others to their local bookstores, there might still be a gap in the market for something new, offering a wider range of New Zealand and international books than a single bookshop or publisher can do alone. “We’re not just sitting on our hands,” Moores says. “We want people to be able to get the books they’re looking for, wherever they are in the country.”