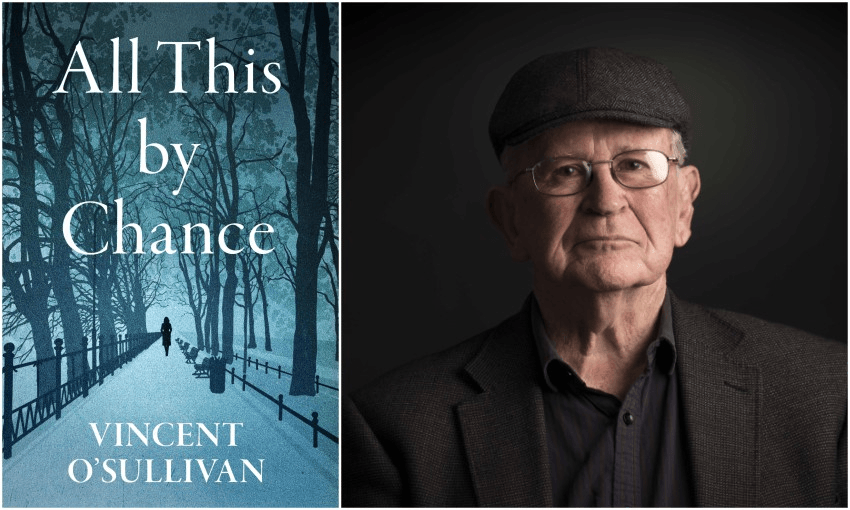

Elizabeth Alley celebrates the latest novel by the masterly New Zealand writer Vincent O’Sullivan.

Is there anyone else like Vincent O’Sullivan? His new novel traces several generations of a New Zealand family, from 1947 to 2004 with the brief, revealing return to 1938 at the book’s end; it opens as the novel’s over-arching character, Stephen, leaves a country full of good food, beaches and available jobs – but also of relentless dreariness, “cows and mud and half a day from anywhere” – to travel to grim, grimy post-war England. It’s the smell that happens first. Image-making is where O’Sullivan is so extraordinarily compelling. The smell of a city – London, burnt to ash, to a cloying, wet, rotting, reeking odour of wood burnt beyond cinder – rises off the page. And the fog that encroaches as Stephen approaches the English coast, the greyness of the estuary and “the fall of flattening light the same colour as the air”.

This is only the first of many senses that permeate the narrative in a way that places the reader so firmly within it. But O’Sullivan also puts the reader to work. The book is divided not by conventional chapters, but by timeframes. And they compel close reading. New characters appear as the plot moves geographically, and sometimes pronouns tend to substitute for names until these too are revealed and add reason to the unravelling. There are changes of structure, place, mood, tone, voice, and perspective as the novel unfolds. Age and experience alter characters. The insouciance of youth coarsens, becomes rough-mouthed and acerbic – and damaged by more recent events. A new generation inherits and tries to deal with a past that seems so reluctant to release its burdens. But the young burn with more passion than those of its elders, who sometimes seem reluctant to let it impose its unwelcome memories on lives that could be better occupied with art and architecture and everyday pleasures than the lurking awfulness they suspect.

The timeframes are sometimes separated by only a year or two, sometimes by 20 or more. They extend broadly enough to include contemporary issues such as people smuggling – an episode that provides the strongest narrative tension in the book, with its heartbreaking outcome. As the plot moves between England, Auckland, Greece and Italy, some of the most potent episodes centre on Lisa, who becomes a missionary doctor in Africa after her training in England. It’s here that the writing has an immediacy and directness sometimes obscured by events in other sections, and catches the mood of Africa with plangent authenticity. In a late evening walk back home from the hospital, Lisa takes in the cooling air, the black tracery of trees and “the plaiting of scents from the trees through the hospital odours.”

In London Stephen’s life changes when he meets Eva, at “an Anglican dance you were sent to by a Jew who thought you were a loner, that I was urged into going to by Quakers”, she muses. Eva, aggressive, assured, determined, confident in spite of the gaps in her history. Stephen, shy and diffident, aware of how uneventful his own life seems in contrast to what he imagines of hers. Eva has no memory of her family, or background. She seems English, having been adopted as a small child by an English family. Then, married, and just as they are about to set sail back to New Zealand, arrives a woman, a lost aunt, damaged and mainly silent, heightening the sense of mystery and raising the secrets that become central to the novel. A survivor of the holocaust.

The secrets hinted at and never quite resolved weave in and out of the narrative and provide its dramatic tension, far more than do its characters, the older generation seemingly invested with a kind of reticence, an unwillingness to unburden themselves of what they think they know. The arrival, later, of a friend of Eva’s unknown mother is a further complication, and the narrative darkens as “the clawing of ancient regrets” begins.

In other sections O’Sullivan employs the devices of an honours student researching the story, and a journalist insistently asking questions, in an effort to uncover still-hidden information. Confused? Don’t be. O’Sullivan is always the captain of his literary ship, superbly in control, though frequently challenging the interpretive faculties of those who sail with him. It’s not difficult to see why, apart from his variously prolific output, there’s a lot of time between O’Sullivan’s novels when they’re as technically complex as this one.

Aside from many moments of startling clarity and enduring imagery, there’s also an inescapable filament between writer and reader. Almost as if he’s saying, “I’ll tell you a certain amount, but not too much”. It’s odd, this filament, this piece of gauze stretched across otherwise glittering language, and it sometimes aligns the fiction closer to his poetry. Perhaps it’s also because so much of the story is told in indirect speech. But instead of obstructing the clarity, it also injects the reader more potently with the determination to penetrate and comprehend the horrors of history, and to make this a shared burden, an equally distributed weight. The inference is to stick with it in other words, when the inclination might be that it’s all too hard to follow.

Never far away is O’Sullivan’s tenderness for humankind, and his concern for the many effects of deprivation, particularly on succeeding generations. Instead of trying to embrace his characters into a conventional family structure, here he accepts the need when dealing with matters of religion and history, for people to stand to one side of it, and watch what happens.

This novel is engaging, uncomfortable, perceptive, and often frustrating. Those who navigate the calisthenics of the structure are rewarded by some scintillating writing. It requires close reading, concentration, patience and fortitude, the commitment to go where he takes you, in his unshakeable belief that the past so strongly informs the present.

All This By Chance by Vincent O’Sullivan (Victoria University Press, $35) is available at Unity Books.