For many young adults in Aotearoa, the set text for English class may be the only novel they read — or pretend to read — all year. Former teacher Jen Smart underwent a mammoth investigation into the current state of the country’s book rooms to assess what’s on the shelves, and why.

If you ever want to see an English teacher get super fizzed, ask them what books they’re teaching at the moment. That’s because the selection of that book is one of the most agonising decisions they will make all year. The Class Text, after all, represents a huge chunk of time and energy – probably between six and eight weeks of teaching, revising and assessing time over a school year. They’ll mark and feed back on a stupid number of essays about this book and by the time term four rolls around, everyone will be thoroughly sick of it.

These days, though, some high school students may not study a novel at all. People are often surprised to learn that in Aotearoa there’s no “required reading” or any obligation for schools to teach an extended text: English teachers may choose to focus on teaching short texts or poetry with students responding to them in the end of year exam. Gone are the days when the Shakespeare texts were prescribed at the start of each year, that’s for sure.

This is a good thing.

Although there is strong guidance from subject associations and NZQA examiner’s reports around titles, it’s entirely up to individual English departments and teachers to make decisions around what gets bought and taught – as long as it meets the complexity and sophistication criteria set out by the New Zealand Curriculum.

This creates endless opportunities for teachers to create lively, engaging programmes centred around texts that reflect the students studying them. English teachers (lifetime lovers of metaphor) often talk about teaching a blend of “mirror and window” texts; some that reflect the reader’s world and others that allow a view of unfamiliar territory.

This is not to say all reading in secondary English classes is of taught texts; with chapter questions, plot summaries, theme analysis and all those things that ruin the allure of a story well told – so the teenagers say, anyway. As English teachers take great pride in noting, theirs is the only learning area that mentions “enjoyment” in the curriculum document so plenty of student-selected and just-because reading happens in classrooms too.

Reading a book for pleasure is not the same as reading for an English class, though, and students too often associate reading with school work. This can add tension to the selection process knowing that for some students, it will be the only book they read this year. Do you go with something with a pop culture connection, or something that they “should” read? The battle royale nature of The Hunger Games gives a contemporary context to the ages-old story of class struggle, but maybe Animal Farm has more literary merit?

No matter what I ended up choosing, I’d always hope that this would be the book to turn my students back onto reading, or at the very least invite them to take a perspective different to their own. The shared reading experience is a powerful one, particularly in a class with 26+ young and emerging worldviews in the mix.

So how does a teacher choose a book?

More often than not, it comes down to pragmatics: what’s in the actual, literal book room. When an English teacher begins at a new school, it’s the first place they go. Those stacks of titles on tinny bookshelves, sealed in slightly wrinkled covering film, with yellowing paper lists of student names glued to the inside back cover – they have a subtext all of their own. Is this a safety-first English department that sticks to the classics? Are they committed to the representation of diverse voices? Would they take a risk on a Booker Prize short-listed novel just to try something new? Are they running on a shoestring, patching up old editions each year?

Choices can be majorly limited by budget. It’s very expensive to buy a class set of books for the simple reason that books cost a bomb in New Zealand. This is more so the case for contemporary literature, and is one reason why a head of department might choose to top up existing sets of “classic” texts (usually cheaper) instead of buying something new.

The purchase of 32 copies of a new book is one of the bigger financial decisions an English department has to make and it’s usually made the year before as part of a school’s budgeting process. In the departments I’ve worked in, this has been a collaborative effort – teachers put forward a new text they’d love to teach and a group decision is made — hence the recent appearance in book rooms of popular fiction like Where the Crawdads Sing, Nic Stone’s Dear Martin, Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel or Naomi Alderman’s The Power.

They may also decide to bring back an old fave in light of current events or discourse — Orwell’s 1984 made a Trump-era comeback and The Handmaid’s Tale will remain a staple as long as women’s reproductive rights are a topic for “debate” (so, forever?).

I remember taking up a new position as head of English at a rural Southland area school – among the piles of 1980s PAT tests (the ones with the excellent brown and beige diagonal design) and inexplicable Ministry of Education-produced booklets on the practice of flogging (a social sciences unit?) was a magnificent class set of Ronald Hugh Morrieson’s The Scarecrow.

Who on earth was the bold educator who picked Taranaki Gothic for the seventh formers of this little timber-milling town? I live in hope of meeting them.

Along with student voice and course design, the literary merit of a text is obviously a factor in a teacher’s choice. For text responses being assessed in the external exams, the taught text tends to have support from critics, either a canonical text designated “worthy of study” or one that has appeared on a shortlist somewhere. Often we see texts appearing that teachers have themselves studied at uni — which is perhaps how The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien made its way into book rooms. Is this evidence that we choose literature that has been established as “important” in longer-standing literary canons? Maybe.

The book needs to have “performed well” in past exams, meaning that students must be able to respond to it critically, with insight and originality. And back to pragmatics — it’s helpful if there are teaching resources available (meaning pre-created documents laying out ways to interrogate or respond to the text). An English teacher will likely have at least four classes, each studying a different novel throughout the year.

As it turns out, trying to review the books rooms of English departments of Aotearoa was a ridiculous undertaking – there isn’t any current and reliable research into typically studied texts in secondary schools.

So I narrowed the scope in an attempt to find the ten most commonly taught novels (or “extended written texts” in English-teacher-speak) at senior levels, Year 11 – 13 (that’s Form 5 – 7 for those of us who grew up going to English class without a cellphone in our pocket).

I know from experience that schools are looking hard at their book rooms and working to include more voices that reflect contemporary Aotearoa, its indigenous perspectives and diasporic complexity. It appears though, that there is plenty of room to be made for such voices at the senior end of the curriculum, which seems to be dominated by some very familiar titles.

What books are young people studying at high school these days?

This quest to create a zippy literary listicle required the big guns: the New Zealand Association for Teachers of English (NZATE) and the School Librarians Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (SLANZA).

I started with a long list from my experience of stocktaking and organising school book rooms around Te Waipounamu, and 12 years spent with English teachers. From there, I went through the examiners’ reports for the written texts standards at NCEA Level 1, 2 and 3 which often comment on which titles were successful in the exam and those that were less so. I cross-referenced this short list with the results of a survey run by NZATE in 2022, one that simply asked teachers what titles they were teaching at each year level.

I then took my refined list to the school librarians to confirm. (August 7 – 11 was School Library Week, just saying. Go thank a librarian.)

What came out of this process were the titles below. While the lack of diversity and Aotearoa voices might surprise some, be reassured that there is wider representation in texts chosen for study – but probably not in novels. Students are more likely to encounter a wider range of voices in the study of short stories, poetry, film and non-fiction texts.

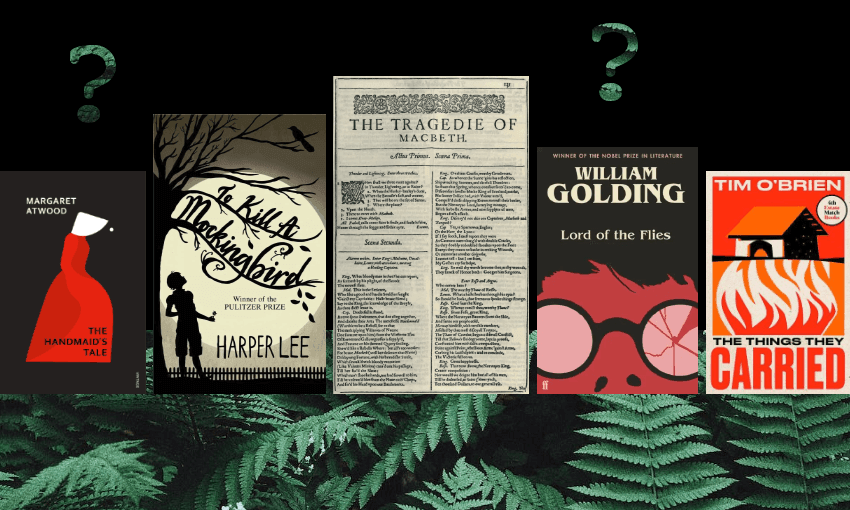

The 2022 Level 3 examiner’s report notes: “Many candidates seem highly engaged with their chosen texts which included good numbers of New Zealand and Pasifika texts. However, the most common texts include The Handmaid’s Tale (Margaret Atwood), The Great Gatsby (F. Scott Fitzgerald), 1984 (George Orwell), The Things They Carried (Tim O’Brien), and Othello (Shakespeare).”

The use of fresher texts was also encouraged back in 2020’s Level 2 report, saying it was “pleasing to see a range of contemporary Māori and Pasifika writers being studied, including Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner, Tayi Tibble, and Glen Colquhoun.” Editorial note: Glenn Colquhoun is in fact Pākehā.

Anyway, here are the titles that cropped up most, with a bit of commentary, where available, from young people who have studied them.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985)

Hats off to Margaret. She’s a multidisciplinary powerhouse who continues to impress young people with her scarily relevant dystopian settings. Despite being published when I was one year old, this was the title that appeared most frequently across all the sources I looked at. Increasingly students are studying the television series as a visual text too.

The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

There was a big resurgence in teaching Gatsby after the lush Baz Luhrmann adaptation came out (pop culture making literature relevant again, yay!). I get that the critique of vapid consumerism is useful for young folk nowadays, but is pursuit of the American dream a relevant theme?

“Some of the messages we learn from The Great Gatsby we see a lot through other media and even celebrities’ lives. I also think that some of the older English texts and films we do in class make it feel like we’re holding on to the old views that aren’t progressive in the way that we are trying to be now… Personally, my favourite English studies I have done were in year 9 and 10 and they were ones written or directed by women, or newer ones that support and celebrate all people. So, my view on whether The Great Gatsby is worth studying is that, yes it can be. It is worth learning from, but maybe we should be making an effort to do newer texts and films, especially in the senior school, instead of just defaulting to the ‘classics’.” (Sienna, Year 12)

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee (1960)

If it was published today, would this novel receive the same response from literary critics as it did in 1960? I re-read it a few years back and was surprised at what a drag it was. It’s a series of vignettes (admittedly some very powerful ones) rather than a cohesive narrative. Given there are so many stories of racism and corruption in the justice system these days – and from people with lived experience of it – there has to be better options. One of them is Craig Silvey’s Jasper Jones, which was mentioned a lot by teachers and is essentially To Kill A Mockingbird set in Australia. Maybe it’s time for Scout to sign off?

“There are a plethora of newer books covering similar topics in more fun and interesting ways that should be explored more. Although the book has a large amount of resources to assist with studying and covers important topics, To Kill A Mockingbird is an outdated story that students will find uninteresting due to its challenging vocabulary and slow plotline, and there are far better books for kids to study that will keep them engaged and actively learning, as opposed to feeling forced into reading a boring book they don’t enjoy.” (Oscar, Year 11)

Animal Farm by George Orwell (1945)

I’m not going to lie, what this book really has going for it in a classroom setting is its length. It’s short but packed with teachable moments – satire, allegory, propaganda and totalitarian regimes. It’s one of those novels whose context is perhaps more appealing to young people than the narrative itself, given that curiosity about history and politics often builds in Year 10 and 11. If I had to choose one novel to study with a class though, for me, this wouldn’t be it.

“Animal Farm exhibits how quickly a communist government can collapse and become a complete dictatorship, as well as explaining the in-depth hierarchy of the supposed communism. Animal Farm has a very important theme that is documented to the readers throughout the entire novel, which is the theme of power and how it corrupts. This novel constantly challenges students’ ideas around dictatorship and hierarchy, and has very specific moments that will open students’ eyes to a different understanding about communism and the corruption of power. Overall, I believe Animal Farm is an important book to study in New Zealand’s education system.” (Melody, Year 11)

Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1954)

Like Animal Farm, Golding’s novel tends to be taught at Year 11 or lower down in the school. It was worth including though, given the number of times the title came up. I was ready to loudly proclaim that the teens-in-the-wilderness trope is now covered by Yellowjackets, The Wilds and Steph Matuku’s Flight of the Fantail but the students who reviewed it were really quite positive.

“It’s worth noting what Lord of the Flies is really about, it teaches us of the dark side of humanity and about how civilisation is related to its name, it keeps us civil. Without societal expectations, there would be chaos. Lord of the Flies is an important book to make us realise how unreasonable people can become, it gives us multiple perspectives of the situation and really puts the reader into the boots of the characters. As well as teaching students the importance of civility, this book is able to provide us with a broad range of vocabulary which is important for a student to understand and thrive. Overall, I think that this book is a worthy read and conveys an important message, so I would recommend it to teachers.” (McKellar, Year 11)

Macbeth by Shakespeare

The Bard that launched a thousand teacher resource guides and graphic novel treatments is still a firm favourite for Year 12 students, and occasionally Year 11. I studied it in sixth form and could probably still write an essay about “vaulting ambition which o’erleaps itself.” The themes are timeless of course, but what’s beautiful about teaching Shakespeare is taking students into the linguistic swirls and layers.

1984 by George Orwell (1949)

Is there a more iconic year in all of literature? Anthony Burgess, author of A Clockwork Orange, called 1984 “an apocalyptical codex of our worst fears”. When things get scary and messy, when language becomes meaningless and truths are mangled, this is the book we want young people to have read. It’s widely taught in English-speaking curricula around the world, so most people will encounter this novel as a young person. It may not strike a chord until much later in life, though.

The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien (1990)

It was surprising to see this title turn up so often. There is some relevance for young New Zealanders given our minor involvement in the Vietnam War, I suppose. The book grapples with a society’s emerging understanding of PTSD and the impact of witnessing such atrocities on a generation which must be an interesting perspective for young people to take. It is likely to be a student’s first experience with postmodern literature too – the dismembered order of stories, blurring of fiction and truth and a damaged, unreliable narrator make great teaching fodder.

Othello by Shakespeare

Annalise (Year 13) has the popularity of this text choice nailed:

“Othello presents students with an ultimatum; think critically, or suffer the consequences. In order to thrive in a world heavily influenced by ‘truth’ presented by mainstream and social media, students must each learn to critically analyse every piece of information brought before us. By bearing witness to the dire consequences suffered by Othello as he refuses to think with a critical mind, students in New Zealand are able to learn from Othello’s mistakes and learn for themselves the utmost importance of critical thinking. And, in a world growing significantly more rampant with misinformation and disinformation, it would be a moral crime to not teach the emerging generations how to live a life unaffected and unmanipulated by the modern day Iago; fake news.”

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini (2003)

Friendship, loyalty, betrayal – and a swift-moving plot. It’s long but students find the story quite compelling. It has been popular for a while now though, and word on the street is that it’s becoming difficult for students to write an original take on it in exam conditions.

“Having done this year’s novel study on The Kite Runner, I believe that, although graphic, the emotions and thoughts that it provokes make it a stark reminder of the events constantly happening around the world that we are often completely blind to. Writing about the text from this perspective makes real world connections and in-depth analysis simpler to make and means that ‘perceptive’ insights are also easier to make. Therefore, I think that, as long as the teacher prefaces the reading of this book by ensuring students do a small amount of research about Afghanistan during this era and a general idea of the events in Kabul at the time, The Kite Runner that has both a plotline and features that make it easy to analyse. Beyond this, it is simply a very interesting read.” (Abby, Year 12)

Where are the local writers?

While they may not be widely represented in the novels taught at senior level, Aotearoa voices certainly are being studied in schools. The vast majority of teachers reported that they use New Zealand texts in their programme (or want to include more of them). However it appears that our voices are more likely to be heard in poetry, short story collections or on screen. Names like Chris Tse, Tayi Tibble, Tusiata Avia and Selina Tusitala Marsh regularly came up, as did Witi Ihimaera, Hone Tuwhare, James K Baxter, Fleur Adcock and Brian Turner.

In discussions about extended texts, a few New Zealand titles did appear, dominated by Patricia Grace: Cousins (the film seems to be more popular though), Tu and Pōtiki. Lloyd Jones’ Mister Pip is still going strong and there were a few contemporary offerings that could easily become mainstays in the book room: Tina Makereti’s Where the Rekohu Bone Sings, Bulibasha by Witi Ihimaera, Coco Solid’s How To Loiter in a Turf War and Rebecca K Reilly’s Greta & Valdin. Becky Manawatu’s Auē came up too – one to “go carefully” with, as the curators of Reading Stories From Aotearoa say.

If literary merit is a driving factor in text choice though, we’d be seeing a lot more Katherine Mansfield, Janet Frame, Keri Hulme, Eleanor Catton and Ashleigh Young mentioned in the examiner’s reports, surely. Their work is no less accessible for rangatahi than the top ten listed above and has international recognition, yet we hesitate to offer it up for study at higher levels of the curriculum.

It could be a whiff of cultural cringe haunting us – we’re over that with New Zealand film now, thanks to Taika, so let’s hope literature is next in line for the “they really like us!” treatment.

There are trends to contend with too. Texts fall in and out of favour, and reports of new ones that “work” with students can take a while to filter through the English teaching kūmara vine. There’s budget constraints, of course, and the considerable time investment that comes with developing resources for new texts.

Currently, New Zealand publishing is in a very healthy state, with guidance around fresh local texts strengthening all the time. Read NZ Te Pou Muramura’s wonderful teacher-curated selection, Reading Stories from Aotearoa New Zealand displays the many merit-worthy titles on offer for teachers. As the introduction mentions: “Having a living, up-to-date list of books that represent our place and our people has never been more important.”

There’s also the Aotearoa New Zealand Review of Books, publishing monthly reviews of new releases, and the Academy of New Zealand Literature who publish in-depth features, “exploring the diverse strands and vibrant voices of our contemporary fiction, poetry and creative nonfiction.” Both have .com URLs, a digital planting of our flag on the international landscape of literary criticism.

What then, does the Aotearoa New Zealand literary canon include? Which of our writers should young people encounter in their time at school?

Every time we put a book in front of students to study, we’re saying “this literature is worthy of your close attention”; “these words and ideas are important”. But what does it say about our self-image if we’re not setting New Zealand novels for close study? When we prioritise external voices and experiences over our own for those six weeks of intensive shared reading, we’re stunting our literary growth.

As Te Mātaiaho, the refreshed NZ Curriculum turns teachers more strongly towards place and identity, our book rooms are a good place to start conversations.