Seemingly separate government decisions have increased uncertainty in the construction industry. How will it rebuild momentum and confidence?

Getting buildings built is a long and complex process requiring vision, a lot of money and commitment. More importantly, perhaps, it requires confidence and momentum to ride out the highs and lows that come with any complicated pursuit. A year on from the election, it’s fair to say that the construction industry has lost its momentum, and it’s not clear how we’ll get it back.

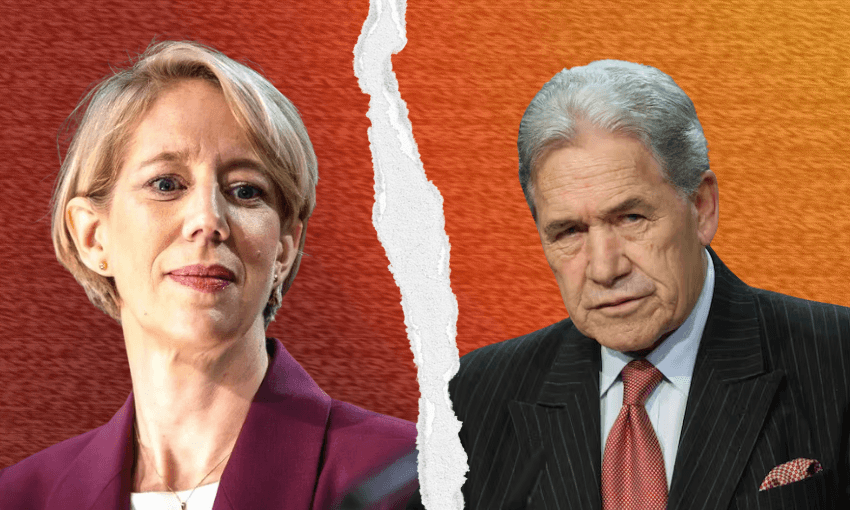

While the recession was perhaps inevitable, the coalition government has impacted the construction industry in ways that makes the course to recovery unclear. Seemingly separate decisions have disrupted the industry, often abruptly, increasing uncertainty and displacing people, likely delaying the industry’s ability to respond when the time comes.

The future of Kāinga Ora as the primary developer of social housing is in doubt – the procurement of services associated with new construction projects, and the construction of existing projects, stopped some time ago. There are projects consented and ready to go, but the obliteration of Kāinga Ora’s design and development teams last week appears to be their death knell, with no one left to deliver them.

Unsurprisingly there’s suggestion that the private sector will become a larger player, with Community Housing Providers becoming the development vehicle of choice. The industry’s waiting to understand what that means and see how skills, knowledge and money will need to be distributed to enable it to happen. Meanwhile, no one’s claiming to have solved the housing crisis.

The education sector is the same. Work on schools, led by the Ministry of Education, was brought to a grinding halt. Designers were asked to halve construction budgets, irrespective of any need to plan for the future, resulting in a return to cheap, short-sighted outcomes. Pre-fab manufacturers rejoice.

Again, the private sector emerges, with 15 charter schools progressing beyond the application stage. While David Seymour has suggested these 15 schools could be open for term one next year, either they’ll be making use of existing buildings (which is admirable) or they’ll be funding, designing and consenting new ones. Either way, it feels like it’ll be a long time before we see contractors building much in the education sector. These schools need to mobilise, establish development teams and build momentum, all with bespoke requirements. Further delay, further disruption.

A particularly deliberate example of disruption emerged a fortnight ago with the Ministry of Health choosing the shortlist of design teams that will deliver the majority of public health projects in the foreseeable future, including Whangārei and Nelson Hospitals. While the list of teams that missed out is dominated by those that have been responsible for public health work over the past few decades, the list of successful applicants is dominated by firms better known locally for big-box retail and apartment projects.

Healthcare designers are some of the most specialised in the industry. This isn’t surprising given that their work contributes to saving lives. The redistribution of that expertise, to the companies that eventually win the ministry’s work, won’t come easily. Existing employers will fight to hold onto them, target private healthcare and projects overseas, denying the successful consortia the skills they need to deliver the public healthcare facilities they’re engaged to design. It’s a sad day for the public healthcare system.

Finally, if we were to rewind the clock to before the election, the country had scores of people designing light rail, harbour crossings and inter-island ferry terminals. As expected, we’re now talking about roads.

The people required to design and build urban light rail are quite different to those who carve roads through our countryside. The body of public infrastructure work being done before the election brought companies and their people to New Zealand with the promise of a pipeline of work. Regardless of where you think our infrastructure dollar should be spent, the collapse of that pipeline will see those people and companies leave, less likely to return, not only because of the type of work on offer, but also the severity of the change.

The housing, education, healthcare and infrastructure construction sectors have all seen massive disruption over the past 12 months. There’s no doubt that the construction industry is disoriented and depleted. Momentum and confidence has been lost. For many it will have been enough to leave New Zealand, or their professions, unable to tolerate the highs and lows any more. For those who remain, the future is uncertain.

The New Zealand construction industry tends to be a pretty resilient bunch of people. The boom and bust cycle is disappointingly familiar. We also know that our individual success is determined by our ability to work together, contributing to each project and ultimately a stronger and better country.

We’ll respond to the opportunities when they present themselves, slowly rebuilding momentum and confidence, but at the moment the course we’re being asked to navigate is unclear. Since being elected, this government has made a series of decisions that speak as loudly about their political ideology as they demonstrate a lack of any plan.

To regroup, organise ourselves and contribute to making New Zealand a better place to live, learn, work and play, we need a vision. Where is it?