Jake Millar was loved, admired and critiqued. He died earlier this week. Duncan Greive asks why we continue to place founders on such impossible pedestals.

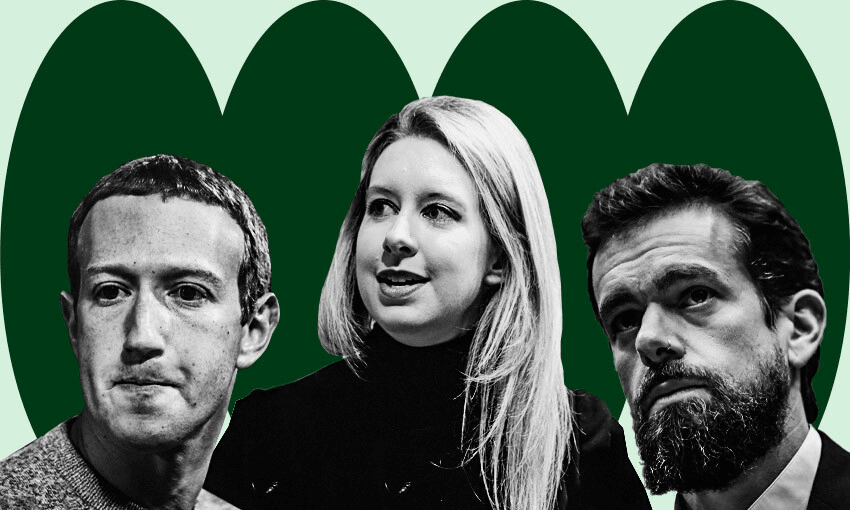

It’s been a bleak few weeks for major tech founders. Elizabeth Holmes is on trial for the way she ran Theranos, a revolutionary blood-testing company that faked it until it made people really sick. Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook has created a book-long series of scandals boiling down to its inability to effectively moderate the content of its users. Jack Dorsey, the co-founder of Twitter, has resigned after a far more mundane failure: his social media company’s share price has stalled while other tech companies’ has gone stratospheric.

Yet of these three figures, Dorsey is by far the most sympathetic. He’s easily caricatured through his intermittent fasting and stated desire to move to Africa, but also has somehow ridden through these years as a multi-billionaire with self-awareness intact. “There’s a lot of talk about the importance of a company being ‘founder-led’,” he wrote in his resignation letter. “Ultimately I believe that’s severely limiting and a single point of failure.”

All of this is connected to what NYU professor Scott Galloway calls the “idolatry of innovators, or founder fetish”. It has its recent cultural origins in the brilliant but brutal way Steve Jobs’ vision for Apple was realised, though has roots tracing back through Bill Gates’ Microsoft prime and the Silicon Valley origin mythos of Hewlett-Packard, and probably runs back to John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt and even Jesus, if you really draw a long bow. Many young people grow up dreaming of joining that pantheon, no matter how remote the possibility.

There are two main issues with the founder myth. The first is a matter of simple fact: companies like Facebook and Twitter have thousands of employees, some of whom have profound influences over their outcomes. Apple is unimaginable without the influence of Jony Ive’s design. Theranos appears to have been driven as much by its president, Sunny Balwani. Instagram and WhatsApp, Facebook’s main growth vehicles of the last half decade, were invented by other people and just bought by Zuckerberg.

On some level this societal and media propensity to build founders up into mythic figures who contribute more to their companies’ success than possibly could is banal. It inflates egos, makes them put their names on the side of hospitals that don’t want them, get jacked or name their children Æ A-12. It’s a Marvel movie come to life, both embodying and befitting this bizarre era.

The long, sad tail of the tech titans

Then there’s Jake Millar. Over the past few days I’ve been debating whether to write about his tragic death. He passed away in Kenya over the weekend aged just 26, having experienced the giddy highs and crushing lows of New Zealand startup life more publicly than most. He and I corresponded on and off for some years, and The Spinoff published a series of stories about him and Unfiltered, the company he founded aged just 19.

Unfiltered was built around a collection of soft-focus interviews with wealthy and often internationally known business figures, aimed at an audience of aspiring entrepreneurs. It never quite settled on a business model, but his subjects enjoyed his attention, and sometimes invested in Unfiltered at increasingly heady valuations.

The stories The Spinoff published about Unfiltered were not always flattering. At times they upset Millar, which was how we first met – he got in touch with a major sponsor to express his displeasure. We exchanged phone calls, which were initially testy, but by the end amicable, even warm. The last piece we published about him was an epic story that captured the full sweep of the Unfiltered journey, from its wide-eyed beginnings through the rancorous reaction to its low-priced sale.

Despite that last story doubtless having uncomfortable moments, I know Millar – who spoke to our writer for over six hours over various interviews and sent upwards of 20 lengthy emails through the course of its reporting – felt the final feature captured him and the Unfiltered journey in all its complexity. I know this because he said as much in the aftermath.

In recent days there have been some heated responses to Millar’s death, including a number of widely shared posts from other Aotearoa founders in the technology space who were understandably shocked and deeply saddened by the news. There has been talk of “trial by media”, of him being hounded and harassed and very direct lines drawn between some reporting and his fate. This has largely been driven by founders who feel the media has treated them poorly in the past.

Yet Millar, like almost all founders, actively and adroitly courted relationships with the media. This is a given, almost a necessity, with startup founders, who seek to deploy the media to gain profile that can be used to attract attention and investment to their ventures. Despite being furious about our coverage on one occasion, Millar enjoyed it at other times, sharing stories on social media and sending a bottle of champagne after one story ran. This is part of the imperfect and sometimes co-dependent relationship that exists between startups and the media.

The reality is that journalism contains multitudes. There is a whole ecosystem that fawns over those possessing big dreams, puts them on magazine covers and lists on the way up. There’s another that is more sceptical – it examines whether those ideas have merit, and figures out what went wrong when things inevitably do. You cannot engage with one without alerting the other, and the job of the latter is in part to bring public attention to stories of public interest. When millions of dollars are lost, or the government makes a large investment in a teenager’s company, it’s important that it should be scrutinised.

This whole process is significantly amplified when you gain investments from the rich, prominent and powerful, and they go out of their way to make huge claims on your behalf. Advertising legend Kevin Roberts called Unfiltered “unstoppable”, and said that it could “disrupt every business education programme the world has ever seen”. Yet when it fell apart, he and most of his fellow investors failed to respond to requests for comment.

Through this week, as reporting on Millar has been subjected to intense critiques, it seems strange that his investors have escaped a similar trial. The ageing captains of industry saw in this bright-eyed boy a reflection of their young selves and uncritically invested in his firm at valuations it would struggle to justify. Without those investments there was no story, and their ducking for cover during that period of heightened scrutiny was notable.

Still, none of this changes what Millar went through, or those other tech founders that lived the unicorn dream. If there is a thread through the wildly divergent fates of Holmes, Zuckerberg, Dorsey and Millar it’s that the founder myth is doing damage to both society and individuals. Yet a major change to the fundamentals of journalism, as some seem to be proposing in the rawness of grief, feels like an inadequate solution. Instead, we might benefit from a more honest sense of both who contributes to the successes of these entities, and of how complex and difficult it all is. And those who invest and boost when the founder is on the up should be willing to show up and fess up when the thing falls over, as it mostly does.

Where to from here?

The whole of the tech and startup sector feeds off the founder myth. It’s understandable – an easy narrative hook on which to hang a complex story. But anyone who has spent any time in or around startups knows that the stories told about successful startups inevitably obscure the messy reality. The figures who contribute disproportionately to founders’ breakthroughs, and the missteps edited out of the final picture.

Rowan Simpson – who played key but quiet roles at three of New Zealand’s most successful startups in TradeMe, Xero and Vend – wrote on this theme on Sunday, hours before news broke about Millar. He detailed the moments in those three iconic companies’ backstories during which they almost didn’t make it. These function as alternate realities which would have given us very different conceptions of the likes of Sam Morgan and Rod Drury. The airbrushed media portraits of founders on the way up inevitably gloss this reality, which only makes the shock of just how hard and uncertain it is all the more profound for those who chase the myth into founding their own companies.

Millar’s tragedy is unique, as every life is. But if there is a lesson to be drawn from it, critiquing the media seems a shallow one. Instead perhaps we should focus on getting everyone involved in business to be more open about what’s hard, what failed and just how arbitrary success is sometimes. Founders are ultimately just people, as capable of brilliance and of being humbled as any of us. Get rid of the mythos and allow for the complexity of reality, and we might allow them to recover from the consequences of both success and failure with their lives intact.

Where to get help

Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor.

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP)

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234, email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO). Open 24/7

Depression Helpline – 0800 111 757 or free text 4202. This service is staffed 24/7 by trained counsellors