A new study shows just how rapidly Facebook’s teen audience has collapsed, raising important questions for New Zealand media, writes Duncan Greive.

A major new survey of the online behaviour of US teens shows just how fast their behaviour is evolving, particularly the pace of migration from once dominant platforms like Facebook to the ascendant TikTok. The Pew survey backs up data from NZ on Air’s “Where are the Audiences?” survey, which will release a fresh youth-focused survey in October, and suggests that the government’s merger of TVNZ and RNZ will face a profound challenge in reaching the young and diverse audiences it seeks.

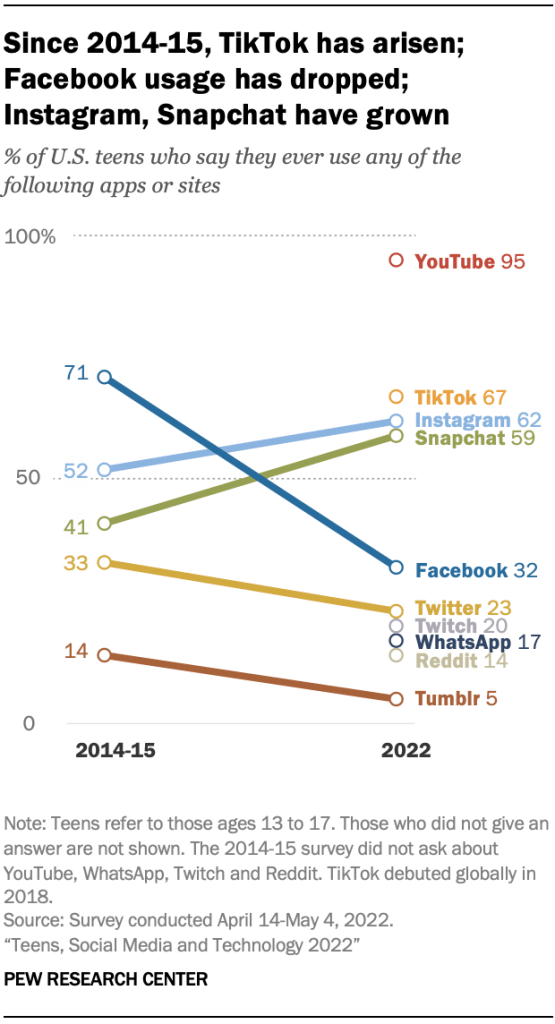

The Pew survey was a sequel to one carried out in 2015, well before TikTok was even founded, and shows the pace of change through that period. Most notable is the rapid decline of Facebook, which was then by far the most popular social app for teens, but has dropped to a distant fourth in just seven years.

The question posed asks whether the platform is ever used – suggesting that just a third of US teens even have a Facebook account. By comparison TikTok, Instagram (owned by Meta, Facebook’s parent company) and Snapchat all register well over 50% usage rates among US teens.

Follow Duncan Greive’s NZ media podcast The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

Why does this matter? The behaviour of teenagers has been subject to scrutiny and critique for centuries, but particularly since marketers and sociologists took note of the predictive power of teenage preferences for society as a whole in the 60s. Teen behaviour is now also obsessed over by the tech companies that increasingly shape our lives. Facebook and Instagram, for example, are swiftly overhauling their user experiences and algorithms to try and become more appealing to teens, while also betting the house on the Metaverse being a thing. They view winning back teens as existentially important. Based on this survey, they might well be right.

The mega trend

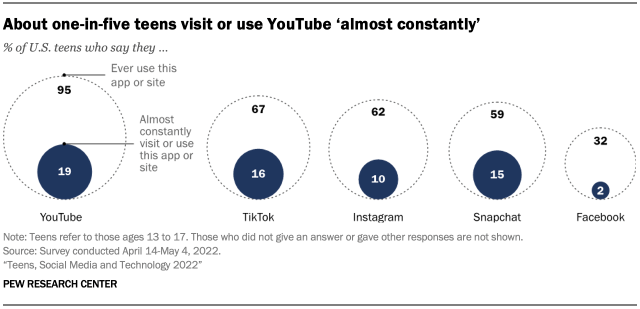

The most immediately apparent takeaway from the Pew survey is the rise of video. The top four sites all have a major video component, and the top two have almost no other functionality of any consequence. YouTube is a colossus of unmatched ubiquity, with 95% of US teens using the platform, just shy of the 97% who are online at all.

The next three, and the only other platforms with penetration north of 50%: TikTok, debuting at a mind-melting 67% and Instagram and Snapchat, essentially tied at 62% and 59% respectively. Below Facebook (32%) sits a bundle of more specialised social apps like Twitter (23%), Twitch (20%), WhatsApp (17%) and Reddit (14%). Of that group, only Twitch is video-centric, but the fact that a platform built to host livestreaming of gaming (though it has become host to much more) is two-thirds as popular as Facebook shows just how much video has eaten the internet alive.

What’s interesting to think about is whether TikTok is social media at all, at least as we used to know it. It characterises itself as an entertainment platform, it’s deeply disconnected from the social graph, and there is no consistent nudge to post – it’s perfectly happy with you just watching. Add that to the total conquest by YouTube – another platform for non-posters – and it shows teens can live perfectly contented online lives just consuming video and messaging. Which might be a better scenario than the knotty, anxiety-inducing public behaviours this consumption has replaced?

The winners

The Pew study points out that “TikTok and Snapchat stand out for having larger shares of teenage users who visit these platforms regularly. Fully 86% of teen TikTok or Snapchat users say they are on that platform daily and a quarter of teen users for both of these platforms say they are on the site or app almost constantly.”

What’s interesting is that Snapchat has largely stayed in its lane, focused on and beloved by teens. Instagram was able to successfully copy its most popular feature in Stories, and it’s trying to do the same trick again with its TikTok clone Reels. I attended a briefing event for young creators run by Meta this week, and was struck by the palpable fear of TikTok present in the air. Its name was never mentioned, but there were frequent references to the way the Instagram algorithm downranks content featuring a watermark – the signature of TikTok’s cross-platform virality. When your competition won’t even say your name, you know you’re winning.

The losers

Facebook was founded by a teenager in a dorm at Harvard, but nearly 20 years on it’s the undeniable loser here. It has plummeted from 72% penetration – easily dominating the social space – to just 32% today. The New York Times technology writer Kevin Roose caused a stir late last year when he posited that Facebook might be a “dying company”. It remains popular with older people, but dropping 40 points for teens looks irrecoverable. It’s also troubling for Facebook that its biggest audience is poorer white users, perhaps the least coveted demographic in the world.

Twitter, by contrast, also declined, but by just 10 points, to 23%, and now looks like it could plausibly overtake Facebook among teens by mid-decade. This would have been an unimaginable statement a few years ago.

What’s even more troubling for Meta is that Instagram does not look unshakable either. “A majority of teens ages 15 to 17 (73%) say they ever use Instagram, compared with 45% of teens ages 13 to 14 who say the same (a 28-point gap).” This might just indicate that Instagram is a platform typically adopted later in the teen years. Or it might mean that Instagram too is dying, just at a different pace. You can understand the panic in Palo Alto regardless.

The big questions

There are so many. Related to the hyper-growth of video is the decline of platforms that default to text. Will reading for leisure or information become a dying behaviour? As a writer, I hope not, but it certainly looks that way.

Another element which feels important to note is that there is a much lower amount of direct information pushed out of the most popular apps. You don’t say where you are and you don’t select your interests as overtly as on prior platforms. This may well change over time, but the fundamental nature of TikTok seems to lend itself less well to narrow interest-based targeting than Facebook and Google, which might be both bad for those businesses and good for society.

Those designing ANZPM, the new public media entity being built out of the merged RNZ and TVNZ, need to think deeply about this survey. None of these platforms will natively serve you New Zealand content as of right. You can train it to serve you some, and there is plenty on there – but access is a function of your own behaviour. Going to some new government-owned app and consuming professionally produced content seems unlikely to happen. And even if you distribute it well through the likes of TikTok, how confident can you be of it having the impact you desire?

There is also a confronting challenge to everyone from ad agencies to screen production companies. TikTok is the god mode video format right now, the most popular site on the internet. By far the dominant verbal communication form within it is scrappy, straight-down-the-camera speech.

Meanwhile a large chunk of our communications industrial complex is based on attracting audiences with everything from static design to animation to seven-figure film budgets. These are then sprayed onto vast numbers of surfaces, both digital and physical. This has become increasingly a goal of our government, often with the intention of reaching teens and teen-adjacent audiences, as they’re prone to risky behaviours or a lack of awareness about government services.

You can still do that on TikTok – but will it work? This is particularly relevant because while the trends noted by Pew hold relatively strongly for all teens, there are some notable demographic variations. Girls, Black and Hispanic teens all over-index as TikTok users. If this holds true for young, Māori and Pacific audiences, creating content and buying media will continue to get more tricky. (Pan-Asian audiences are more complex again, requiring strategies for WeChat, WhatsApp and more.)

It adds up to a situation in which the top-level platforms used by different demographics are becoming more and more fast-moving, and what those platforms serve audiences is even more diverse again. Short of China-style content and usage restrictions, which no one seems to be proposing, we have no choice but to turn and face this new reality. For everyone in the business of reaching mass audiences, these behaviours are already normal for teens and rapidly becoming so for the rest of us. Now we have to figure out how to collectively respond.

Follow Duncan Greive’s NZ media podcast The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.