The rise of the machines will radically transform the way we work. Jobs will disappear. New ones will emerge. But what if the perceived threat of technology is really an opportunity to be more human?

The machines are coming for our jobs, but we don’t need to freak out about it. Because, let’s face it, most of us don’t like our jobs that much anyway, and there’s other stuff we’d rather be doing. The rise of the machines – automation, artificial intelligence (AI) and robots – is real. Digital humans, powered by AI, will be working alongside us in the future. If you work at Air New Zealand, ANZ or Vector, you’ve already got a digital colleague. They even have names: Sophie, Jamie and Will. If your job is repetitive and programmable, one of these hyper-realistic digital humans might even replace you in the future.

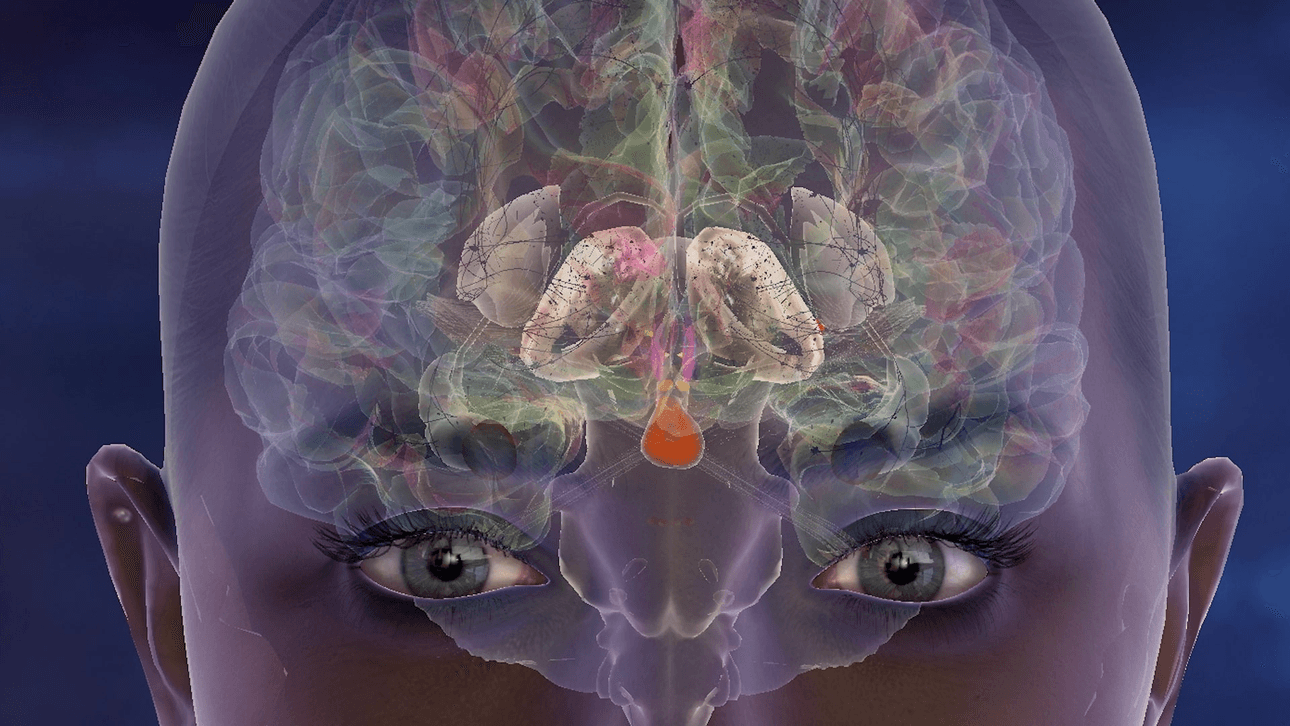

Digital humans, created by New Zealand company Soul Machines, are already capable of replacing and supplementing real humans in some roles. But the technology is just getting started. Soul Machines is currently developing digital humans for the healthcare, human resources, education and entertainment spaces.

“We are already working with some of the world’s leading brands in a wide range of industries and use cases,” says Soul Machines co-founder and chief business officer, Greg Cross.

“It’s an opportunity for almost endless imagination.”

Digital humans are just one example of how automation is disrupting the way we work. Robots are picking kiwifruit in the Bay of Plenty, milking cows in the Waikato, transporting containers at Ports of Auckland, and assisting with surgeries across the country. Self-driving vehicles and smart self-checkout shopping carts are just around the corner.

A Productivity Commission report in April, titled Technological change and the future of work included the prediction that 46% of work in New Zealand was at high risk of automation. That risk went up to 70% for labourers, machinery operators and drivers, and clerical and administration workers.

The OECD estimates 14% of existing jobs could “disappear” as a result of automation and 32% are likely to be radically reshaped.

But New Zealand’s futurists and technology experts don’t think the so-called “robot redundancy” or “jobocalypse” is something to freak out about. They’re optimists who believe humans and machines can co-exist peacefully and productively.

The soul in the machine

The great unknown is just how powerful AI will become in the future. This will determine the extent to which it disrupts the way we work. Right now, AI has what’s called “narrow” intelligence. It’s programmed to complete specific tasks. For example, there’s an AI that can play chess and that’s all it does. There’s an AI that can drive cars, but it can’t teach calculus to high school students… yet.

Humans have what’s called “general” intelligence, a unique cognitive ability to think and reason across different domains and acquire knowledge to apply to unfamiliar tasks and problems.

If AI stays within the bounds of “narrow” intelligence, its impact on jobs will be significant, but limited. The thing is, companies like Elon Musk’s OpenAI and Google’s DeepMind are working hard to build a general AI, the likes of which would be indistinguishable from the human mind. Build that, and AI taking our jobs might be the least of our worries.

Cross says that he’s more interested in building a world where humans and machines work collaboratively, where AI enhances our jobs and helps us to do them better. “We believe very strongly that the work we are doing is about human and machine cooperation, not humans vs machines.”

That’s the future that Sarah Hindle, Tech Futures Lab general manager, imagines as well. She says the conversation around automation has focused on what jobs the machines will take over. But the better question to ask is: how do humans and machines work together in the workplace? Take the example of mental health services, something that’s “woefully lacking” in New Zealand; a digital human can be used as the first point of contact for a patient. It can ask questions, give advice, and provide preliminary diagnoses. And it can do this from any location at any time, on-demand and at a minimal cost. The feedback collected from the patient can be passed on to a human therapist who can assess the case and provide higher-level care.

“Often those digital humans are really good at making initial diagnoses,” Hindle says. “I don’t see it as replacing mental health services as done by humans, I see it as complementary.”

Asked if this human-machine symbiosis would be possible in the future, Cross says: “Absolutely. We are already doing this.”

Mental health is just one example of how AI can help to relieve pressure on overloaded services not by replacing us, but by working with us and freeing us up to focus on more important tasks. Cross says digital humans could also fulfil roles that many humans don’t want to do, like being teachers and doctors in remote, rural areas.

More jobs than we can imagine

Hindle also believes that the rise of automation, known as the fourth industrial age, will lead to a wave of job creation – jobs we can’t even imagine. “If you think of someone entering school now, something like 70% of the jobs [they will end up doing] don’t even exist yet.”

Just 20 years ago, no one could have predicted that a “social media manager” would have been a viable career for a graduate today. And who knew someone’s job title could be “influencer”?

“When I left high school a few decades ago, the tech industry barely existed,” Cross says. Now he’s helping to run a company at the cutting-edge of technology.

“There will, of course, be many changes in the job market and industry in the fourth industrial revolution. Due to an unprecedented number of technologies coming to market at the same time, it will mean some jobs go away, it will mean the creation of new categories of jobs, it will mean reskilling and educating parts of the workforce. It may even mean a fundamental change to how we define the work week or the contribution of value to our societies and communities.”

Human-centred skills

Something that everyone seems to agree on is that innately human traits will continue to be valuable, and may even become more so in the automation age. Traits like creativity, imagination, empathy, intuition – the things that make us human.

“If you think about intuition, for an AI to display intuition you’d have to write it as a process,” says New Zealand future thinking, strategy and innovation consultant, Roger Dennis. “How do you take intuition and write it as a process? Same with empathy.”

Work will also evolve to account for the increasing demand for flexibility, autonomy and purpose, says Future of Work Collective co-founder, Sandra Chemin.

“Nowadays we have a lot of people who are very unhappy in their workplace,” she says. “So we really need to change the way we work and allow people to find what is meaningful to them.”

That could mean rethinking the 40-hour, nine-to-five, five-day work week, something which has barely changed in the last 100 years. It could involve allowing more staff to work remotely, establishing company “hubs” in regional centres, or simply getting better at guiding staff towards more fulfilling work. Over time and with the right education, this could mean fewer people on factory lines or in call centres, fewer corporate suits in poky offices, fewer taxi and long-haul truck drivers, and more people working in jobs that give them a sense of purpose – jobs they actually like.

“Automation will change the nature of work by making work more innovative and novel,” says AI Forum NZ executive director, Ben Reid. “People that are in jobs which are very repetitive and very linear process-driven, those jobs will become more interesting.”

We’re already starting to see this shift towards more meaningful work, according to Hindle.

“I think people coming into the workforce are looking for organisations that are trying to make contributions to social good. Coders want to know the end use of their project – what is my coding going to be used for? Is it going to be ethical? That kind of purpose and ethics is really interesting.”

The future is now

Roger Dennis isn’t falling for the hype. He says the rate of progress is more evolutionary than we like to think. Take banking, for instance: “When was the last time you went to the bank to sit down with a teller and withdraw or transfer money?”

The point he’s making is that the switch to ATMs and online and mobile banking has happened at such a moderate pace that we barely recognise it as revolutionary today. And yet, despite ATMs arriving in New Zealand in the 1980s, you can still see a human bank teller today if you want to.

The future of work is going to be radically different, but we can see it coming. AI, digital humans, robots and machines are already working alongside us, seamlessly changing the way we live and work.

“You’re seeing quite major technology shifts coming through but there’s not going to be any big bang sudden changes,” says Dennis. “[They’re] going to be gradual changes.”

This content was created in paid partnership with the Future of the Future festival. Learn more about our partnerships here.