The vast majority of the world’s chocolate is created by just a handful of large-scale producers. But a growing scene of local ‘bean-to-bar’ chocolate makers like Raglan Chocolate is out to change that.

Ten years ago Mike Renfree was working as a food technologist for an industrial confectioner in Hamilton when they switched to a cheaper type of cacao mass (ground up cacao) that was made with lower-quality beans. To Renfree, the flavour was vastly inferior. He wondered where the cacao mass came from, how it was made, and why the flavour varied so much between two types of cacao.

Through his research, Renfree discovered the darker side of the chocolate industry – slavery within the system. In mainstream chocolate, issues with modern slavery and illegal child labour in the supply chain have been widely reported and documented, particularly in the Ivory Coast and Ghana, which between them produce over 60% of the world’s cacao. The reasons for this shocking situation are myriad and complex, stemming from over 400 years of unethical trading practices, but one of the key factors that prevents remedy is the extremely low price paid for “commodity” or “bulk” cacao. While some farmers are forced to sell high-quality beans at bulk prices, commodity cacao is generally produced for quantity over quality, then sold in huge volumes to cacao-trading warehouses in places like Amsterdam and New York, at a price dictated by Index Futures (the stock market). This price forces the majority of cacao farmers around the world to live below the poverty line.

A more recent and ethical “bean-to-bar” movement has been growing around the world. Also known as “craft chocolate”, this movement revolves around the concept of making chocolate from scratch – from the bean – in very small batches, using specialty cacao. Until around 20 years ago, this was almost unheard of. Today, there are over 20 craft chocolate makers in New Zealand, including Hogarth Chocolate Makers, Ocho and Wellington Chocolate Factory.

Outside of craft chocolate makers, most chocolate companies fall into one of two categories: huge industrial chocolate producers that make chocolate from scratch, such as Mondelez (Cadbury), Mars or Nestlé, and smaller-scale chocolatiers who buy mass-produced pre-made chocolate (known as “couverture”) from companies like Barry Callebaut and Valrhona, and transform it into bars, bonbons, truffles, and various other confectionery. These chocolatiers include the likes of House of Chocolate, Potter Brothers and Bennetts Chocolate.

While there are many different chocolate companies in the world, the vast majority of chocolate is created by just a handful of large-scale producers.

The bean-to-bar movement has set out to challenge the chocolate industry status quo. Inspired by a collective of renegade artisans in North America in the early 2000s, craft chocolate makers have invented ingenious ways to transform cacao beans into chocolate on a very small scale, using bespoke and repurposed machinery. Much like craft beer and specialty coffee before it, the focus is on handcrafted production and the use of higher-quality, rarer and more ethically sourced ingredients.

As soon as Renfree discovered the possibility of making his own bean-to-bar chocolate, he was hooked. He acquired an old, unused stone grinder (for grinding cacao) from his former employer, bought a small roaster, built a tiny chocolate workshop in his basement in Raglan, and started learning as much as possible from online resources such as Chocolate Alchemy on YouTube.

“Maybe I’d been looking for an out from the big business world… We’d been living in Raglan for just a short time, and it’s a really creative community. You feel like you can actually start something, and you’ll get a lot of support from your community. People were like ‘Shit yeah! When are you gonna do it? Can I be a taster?’”

After a couple of years researching and tinkering, Renfree officially launched Raglan Chocolate in 2017 with his partner Simone Downey, who looks after everything outside of the chocolate making. Like most craft makers, Raglan Chocolate is focused on single-origin chocolate that heroes “fine flavour” varieties of cacao, in the same way that fine wine is made with special types of grapes. Most mass-produced chocolate has a generic “chocolatey” flavour, whereas craft bars tend to offer a vast spectrum of different flavour notes, such as cherry, hazelnut, cinnamon, apricot or malt. Bars made with just cacao beans and sugar can taste like hundreds of different things.

Craft chocolate makers don’t just use specialty beans, they also tend to use a higher percentage of cacao, which reduces the amount of sugar in a bar. On average, you’ll find around 20% more cacao in a dark or milk craft chocolate compared to the mainstream equivalent. Cadbury Dairy Milk contains 24% cacao, whereas Raglan’s Milk Chocolate contains 54% cacao.

“With the commodity model, the flavour of the bean doesn’t really matter,” explains Renfree. “There’s so little cacao in the chocolate, and it’s so heavily processed… the flavour of the original product doesn’t really come through.”

Cacao trees grow all around the world in a belt that spreads 20 degrees north and south of the equator. In New Zealand, sourcing beans isn’t always easy and there aren’t a lot of options, so initially Renfree worked mostly with South and Central American cacao from a distributor in Christchurch. This all changed in 2022 when Raglan Chocolate was part of the Pacific Cacao & Chocolate show in Auckland and Renfree met some Pacific Islands cacao farmers. It was a revelation to find that connection so close.

“We realised just how important they saw us to be, in the same way that we saw them… it just felt like, ‘these people are in our own backyard, they’ve got a resource that’s really undeveloped, so the best thing we can do is source from the people that are closest to us.’”

Now all Raglan Chocolate bars are made with cacao sourced from Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. It’s not always easy to source cacao from these countries, as the infrastructure and trading networks are much less developed than those of South America or West Africa, but there are many businesses, government projects and NGOs working to improve supply chains. The amount Raglan Chocolate pays for beans is up to triple the price of commodity and even fair-trade beans. And the price is consistent and stable, whereas the market price of cacao elsewhere is in a constant state of flux. In the world of mass-produced chocolate, the amount of money farmers receive is affected by complex geopolitical and economic factors that have little relevance to their day-to-day lives.

Christchurch-based Oonagh Browne of The Cacao Ambassador has been working with farming communities in Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea for several years, and now supplies beans to around a dozen craft chocolate makers in New Zealand. The Cacao Ambassador runs a variety of projects in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands, with a mission to empower cacao-growing communities, educate chocolate consumers and makers, and build community through cacao. While this has helped to grow meaningful connections between farmers and chocolate makers, as well as giving farmers a vision of what’s possible when they work outside of the mainstream chocolate market, the impact has been limited as the craft chocolate sector is still niche – currently it accounts for only around 5% of the global chocolate market.

A desire for change on a bigger scale has led to a new collaboration between Raglan Chocolate and The Cacao Ambassador. Recently launched, Weave Cacao is the first ever couverture made in the Pacific Islands, and it’s now available for chocolatiers, pastry chefs and home bakers in New Zealand, in 58% or 70% dark chocolate drops.

While Raglan Chocolate buys only around a dozen 60kg sacks of cacao per year, Weave Cacao aims to buy a shipping container-load every three months. Initially the plan was to vastly expand Raglan Chocolate’s factory, but when Browne discovered Queen Emma Chocolate’s factory in Papua New Guinea, it quickly became clear that contract-making the couverture closer to the farms had many financial and environmental benefits. “About a year ago I got this message from Oonagh, saying ‘there’s a factory in PNG! They can make our couverture!’”

The vast majority of couverture used in New Zealand is mass-produced in Europe, with Swiss company Barry Callebaut being the number one provider. Weave Cacao offers a more ethical, sustainable and local option. “We’re helping farmers and communities rehabilitate farms, put together the equipment they need to ferment and dry the beans, then find the market for them,” says Renfree. “A quarter of our profits will go into a trust, which will go towards building infrastructure and supporting cacao farmers.”

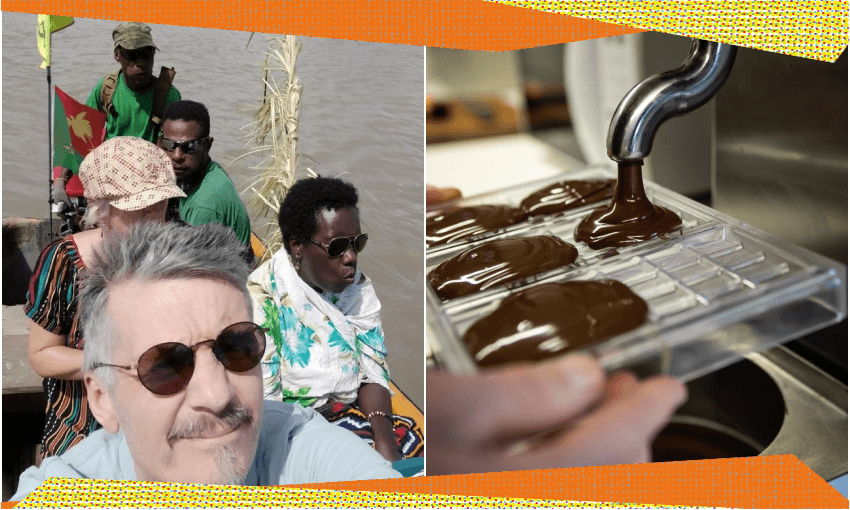

Last year Renfree and Browne visited the two farming communities they’re currently working with, travelling by boat along the vast Sepik River to visit the Mupa community in Momase and Manabo in the Abau district. Their plan is to visit regularly and work closely with community leaders Kingstan Kamuri and Sperian Kapia, in order to build long-lasting, mutually beneficial relationships. It may take time for Browne and Renfree to develop trust and prove that they’re not “gonnas” – the local term for people who come with big plans but fail to deliver. There’s been a century of promises that a decent living can be made from cacao, with very little evidence to back it up. Weave Cacao aims to change that.

“There are hundreds of tons of couverture being imported into New Zealand from Europe, made with beans from West Africa,” says Renfree. “You look at their supply chain and you think, surely we can be more efficient and effective in sourcing a product from the Pacific.”

The ethical issues of the chocolate industry have been discussed and debated for over a hundred years, and while certification systems like Fair Trade, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ have made some small improvements, there are still widespread problems and poverty in the industry. Projects like Weave Cacao hope to offer a totally different solution that works outside of the commodity chocolate market, with a more holistic approach that prioritises the health and education of cacao-growing communities. This isn’t just about paying the farmers much more for beans, it’s about restoring pride, respect and self-sufficiency, while also bridging the gap between farmers, chocolate makers and consumers. The fact that we all get to eat more exceptional and unique chocolate as a result is an irresistible bonus.