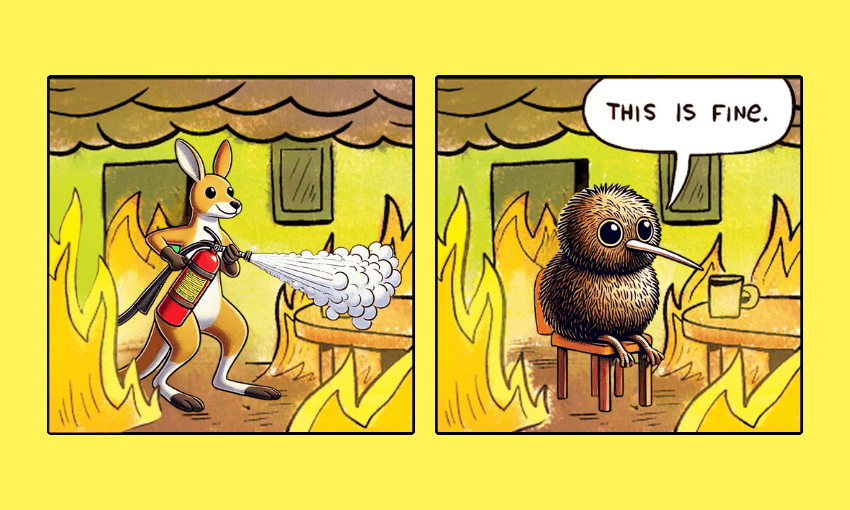

It was a torrid year for almost every aspect of New Zealand’s media. Duncan Greive breaks down the key storylines – and the one vast, existential threat lurking underneath.

Duncan Greive and Glen Kyne discuss many of these stories on The Fold’s year in review.

1. The end of Newshub starts a year-long decimation of TV news and current affairs

A year ago we mourned the end of The Project – it turns out the end of Three’s popular magazine-style 7pm show was just an early warning signal for a cataclysmic loss of regular TV news and current affairs in 2024. TVNZ shut down Sunday and Fair Go, both regularly among its highest-rating shows, along with its midday and late bulletins. The NZ Herald shut down its longrunning Focus bulletin, while Whakaata Māori did the same with Te Ao News just last week. Nothing was quite so shocking as the total loss of Newshub, Three’s entire news operation, which had minted many of the biggest stars of the modern era, and arguably had more influence over the style and tone of our news than any other institution.

2. The TV production sector is hurting as badly as news

When Three’s parent company Warner Brothers Discover (WBD) elected to shut down Newshub, it also announced an end to self-funded commissioning – essentially saying the channel would only screen shows paid for by NZ on Air, or by other funders, such as the Kiwibank-funded On the Ladder. Three had previously been the driver of a boom in locally made comedy (the Jono and Ben multiverse) and reality TV (The Block and The Bachelor).

All that disappeared, with TVNZ not far behind, slashing popular local reality shows and cutting Shortland Street to three nights a week, even with NZ on Air stepping in to keep the soap alive. It meant the local production sector was suddenly more reliant on NZ on Air than ever – with little sign that international streamers view New Zealand as anything more than a cheap location (see story #9) – and thus faces a deeply uncertain future.

3. All this is really about the looming end of purely ad-funded local media

Advertising has always been the biggest funder of local news, culture and entertainment. While linear TV has lost significant viewership over the years, and despite growing eyes on ThreeNow and TVNZ+, the loss of revenue for local media far outpaced the loss of audience. There is a growing sense that the rise of so-called principal media is partly to blame.

However, it’s also becoming clear that advertising alone will not fund local news, culture and entertainment content. Alternatives include audience revenue, like paywalls at The Post or the NZ Herald, or membership models like The Spinoff’s, or an entirely new revenue stream. The obvious candidate is some kind of levy on advertising on large tech platforms. The big unknown is whether the government will work to compel big tech to contribute to local news or entertainment, as both the news industry and production sector have been lobbying for, with increasing desperation, in recent years. More on this in point 10.

4. The paths not taken

It’s easy to sit in the media wreckage of 2024 and find villains to blame. Political inaction or muddled choices certainly played a part – the PIJF eroded trust in news organisations, the Fair Digital News Bargaining Bill might have worked had it not gone two years without passage, while the energy which went into the collapsed TVNZ-RNZ merger might not have been wasted had the concerns of the private sector been addressed earlier in the process. Yet the local media industry cannot ignore its own role in the current malaise. The enormous Covid-era ad spend was a subsidy in all but name, one which could have helped local news organisations push harder into digital futures. It is indefensible that TVNZ+ only started to seriously surface news content this year, and only after marquee shows like Sunday and Fair Go were gone. In a recent interview, TVNZ’s cerebral sports doyen Scotty Stevenson expressed an iconoclastic view which has the ring of bitter truth to it.

All that said: there is a limit to how much innovation might have helped do anything more than delay the current situation – we fundamentally have an untaxed and unregulated sector overwhelming a taxed and regulated one. This is also the case in gambling, as Mediawatch’s Colin Peacock pointed out this past weekend. The only difference is that the government is assiduously working to protect the local racing industry by banning overseas digital competition. In news and culture, it’s still just watching.

5. Stuff boldly pivots to video

When Newshub was shut down, it left a vast hole in local journalism – but also a void at the heart of Three’s evening schedule. Not long after, WBD revealed it was interested in replacing the 6pm bulletin with a cheaper alternative. It received more than a dozen indications of interest from around the world. Stuff emerged as the winning bidder, and has set about re-fashioning its market-leading news site to be far more video-centric. It has two major pieces of video infrastructure high on its homepage, and one of its five verticals at the top points to TFN, aka The F#$%ing News, its weekly Paddy Gower-fronted news magazine show.

It also streamed the Rugby World Cup in 2023, the America’s Cup in 2024 and announced a partnership with Toyota to stream motor racing in 2025. The year was not uncomplicated, with CEO Laura Maxwell resigning after a short 18-month tenure, while head of commercial Matt Headland left not long after. As a private company, little is known about the success of its multiple regional paywalls, but it is at pains to suggest that a recent structural separation of its business is driven by accounting, and not the “conscious uncoupling” its CFO described it as.

Ultimately, Stuff made a bold move towards video, which remains the most important ad format of all. In so doing it has taken what seems a definitive lead in its battle with the Herald for largest digital news audience – for all that it deserves huge credit: none of New Zealand’s major media companies moved further or faster in 2024.

6. Sky quietly builds a wall

Few credit it in the streaming era, but Sky was New Zealand’s original media technology innovator, with satellite and then MySky, all built around a pricey yet essential subscription model, well before it became the default. While aggressive competition from the likes of Netflix has eroded its margins, it has a vast market penetration across satellite, Sky Sports Now, Neon and its new internet-enabled hardware. It has adroitly built up its ad business from a low base, and had an underrated coup in picking up Max in October – taking a potential competitor off the board while also bolstering its own streaming service in one transaction.

It ends the year without a renewal in its pivotal NZ Rugby deal – but NZ Rugby Commercial abruptly farewelled its CEO Craig Fenton less than a year into his time in charge of that organisation. Informed speculation suggests NZ Rugby isn’t wildly confident in its chances of improving the current terms. There is no meaningful competition for those crucial rights – so unless something strange happens, Sky will bank a significant saving, and start 2025 alongside NZME as the subscription-driven local media organisations best-placed to endure the current storm.

7. Taupō goes from two papers to zero – or has it?

In June, the central North Island tourism hub of Taupō boasted two competing community newspapers – The Taupō Times, owned by Stuff, and the Taupō and Tūrangi Herald, owned by NZME. Within six months, the closures of both had been announced. In a year dominated by the loss of major national news brands, it’s worth dwelling on what has been lost in small towns – dozens of community newspapers published their final editions in 2024. They were already hollowed out – it’s telling that when NZME announced in early December that 14 papers would be closed, that was associated with just 29 jobs – but small is far better than non-existent.

The idea that districts as large as Taupō, with its 40,000 people, would lack for a single journalist is deeply troubling. Facebook community groups can perform some useful functions, but not journalism – whole chunks of the country are becoming news deserts, and we will only discover what that means over time.

Still, just yesterday there came some positive news, for Taupō at least, with the Herald being rescued by its editor– now owner – Dan Hutchinson. That might be the future of local media – smaller, nimbler and tied directly to its community. “There was a lot of worry about losing the only newspaper in town,” Hutchinson told me. “It might not make sense for a corporate, but there’s a lot of support for it in the community.”

8. Radio, outdoor and public media resist the tide

Amidst all this destruction, two institutions remain untouched – RNZ, holding the $25m (a greater than 50% increase) funding boost bequeathed by the last Labour government, and NZ on Air, which missed out on the broad public sector downsizing. RNZ has gone on a digital tear, building its digital audience to 1.4m with a much more energetic publishing regime – albeit one which can feel uncomfortably close to duplicating the likes of Stuff and the NZ Herald’s free content. Its radio audiences are down, but the public media created by RNZ and NZ on Air represent rare bastions of stability.

More broadly, radio and out-of-home remain much less exposed to the fire ripping through commercial media. NZME and Mediaworks have offices and connections to businesses and communities in small towns throughout the country – in Taupō, More FM still has a local morning host. Meanwhile out-of-home is a rare local growth story as it digitises, with the startup Youdooh showing that there remain opportunities for new businesses in that area of the market. The only thing which took the shine off out-of-home’s positive year was the unholy debacle that was AT’s outdoor media procurement process, restarting next year after 18 excruciating months.

9. In some key areas, New Zealand is not even a branch office

The Spinoff reported in May that Claire Murdoch and Rachel Eadie, Penguin’s most senior local publishers, had lost their jobs in a restructure. It’s part of a slow but unmistakably steady reimagining of New Zealand as less a market in its own right, more a relatively inconsequential appendage of Australia. A place to be sold into, rather than one with its own identity and culture. As it goes in book publishing, so it goes with film, TV and music – the state-funded part stays still while the commercial elements dwindle.

Some might call this market forces at work, and it’s true that independent publishers have risen into some of the void, while some musicians are having success in the globalised streaming ecosystem. But what feels more typical is the ANZ office of Netflix, which seems to view New Zealand purely as a backdrop to shoot shows and films in, not as a market deserving of culture in its own right.

Perhaps most instructive is the case of Amazon’s Prime Video. It will soon start aggressively selling advertising into New Zealand, with daunting targets being circulated to media agencies. Yet it makes no shows for this country, and recently severed its last real connection, with a New Zealand-based publicity company. Culturally, New Zealand only appears on Prime Video’s map as a revenue line.

10. New Zealand bends the knee

What is the through line here? It’s money, obviously. The media business and advertising business are actually in terrific health globally – Netflix is worth US$400bn, and GroupM projects advertising to hit US$1tn this year, up 9.5% on 2023. People are consuming more media than ever, and payments – for access to content, or access to audiences – are never more than a few clicks away.

So why is the money flowing out of New Zealand at an ever faster rate? Because we’re not even trying to stop it, or even considering the consequences. As of today, the last substantial change to operating conditions for big tech giants was the application of GST to some payments. That happened in 2016, when John Key was prime minister.

Our neighbours in Australia behave very differently. They are in the midst of a five-year digital platform services inquiry, which has discovered a vast array of problems occurring due to unregulated technology services operating in their country. That has produced a raft of legislation, regulation, court cases and fine regimes, making Australia a world leader in the attempt to wrestle back sovereignty from tech platforms, and achieve better outcomes for its people, its businesses and its culture.

In New Zealand, we’re still just waiting, watching and withering away.

For more from Duncan Greive on media, listen to The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.