The Operation Burnham inquiry found serious failings in how the defence force operated, but none of this ‘transparency’ would have come to light if it hadn’t been for two journalists fighting tooth and nail to hold those in power to account, writes Amnesty International’s Meg de Ronde.

When attorney-general David Parker stood up yesterday morning to say the government was releasing the full report into Operation Burnham, he said it was in the interests of transparency. A simple word. It conjures images of ease of access. It implies the government wants to be open.

Nothing about what was released with the report has come easily. And if you’d like me to be transparent, it’s only come about because civil society slogged and pushed to know what our government was doing in our name.

Yesterday it was confirmed that a little girl likely died during a raid by our defence force in Afghanistan, that other civilians lost their lives and that the conduct of our SAS personnel in relation to a prisoner breached the Geneva Convention. The report from the independent inquiry into Operation Burnham also found that senior members of the defence force made incorrect and misleading statements and never corrected them. Despite this, the report has said there was no cover-up. I’d be interested to see the definition of cover-up they’re using.

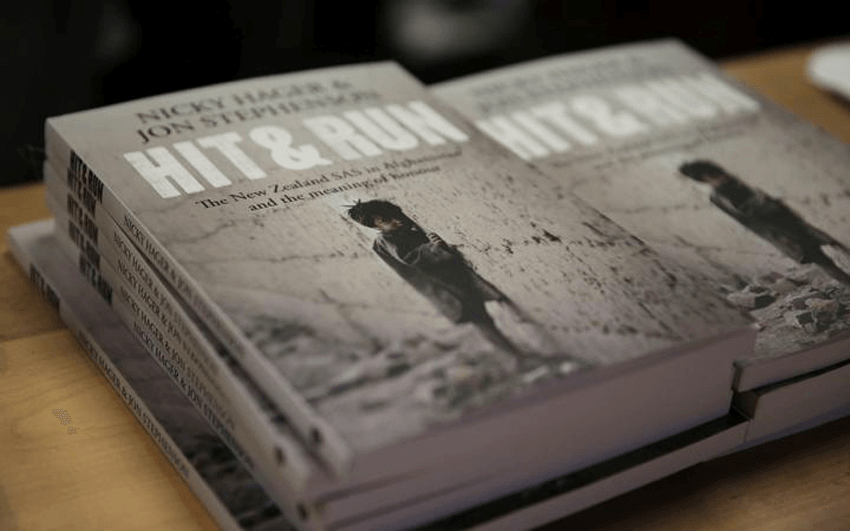

Back in 2017, when these allegations first came to light – as a result of the extensive work of investigative journalists Nicky Hager and Jon Stephenson in their book Hit and Run – Amnesty International Aotearoa New Zealand called on the government for an independent inquiry. Our work in human rights means this is often a crucial call we have to make. It’s not wildly sexy. People like to mock an excess of inquiries.

But, if there is a disagreement on potential crimes, whether they’re of the international variety or not, you need an independent arbitrator. The defence force strongly disagreed with the allegations in the book, as did the defence minister and prime minister (although it now seems politicians were grossly misled by the Defence Force). But we had two journalists who had put their reputations on the line to make a compelling case otherwise.

We did not believe the defence force should be allowed to investigate serious allegations like this themselves. Thankfully, thousands of people agreed with us that an independent inquiry was necessary (the United Nations was also asking questions) and in 2018, the inquiry was announced after continued advocacy from lawyers, journalists and organisations like ours.

But the inquiry itself was anything but transparent. We had very limited access or ability to scrutinise what was said or what evidence was presented. On the other hand, NZDF and other government agencies had huge resources at their disposal to argue their case, spending millions of dollars of public money.

We work with human rights defenders all around the world as governments seek to silence them. Often this means throwing them in prison on trumped up charges or, in the most horrific cases, extrajudicial killings. Here in New Zealand, perhaps we’re uncomfortable acknowledging that’s what Jon Stephenson and Nicky Hager are. Human rights defenders.

After all, they’re often ridiculed by our politicians and others for the work that they do. In 2016 our then prime minister called Hager a conspiracy theorist in relation to his work on the global financial scandal of the Panama Papers. Hager even had his house raided by police in 2014, and received a police apology for having his rights breached. Jon Stephenson had a long-running case of defamation against the New Zealand Defence Force, which had attacked his credibility in relation to reporting on another matter.

Amnesty International takes no money from governments. This is for good reason; it protects our autonomy and ability to speak out against them. We’ve had aggressive calls from ministers and staffers because of what we do. It’s often tough work in New Zealand. Even if we’re not being shot in the street.

So it pays to say that none of this “transparency” would have come to light if it hadn’t been for human rights defenders fighting tooth and nail to hold those in power to account. And I have big concerns that if we don’t work hard, the current government and future governments will only pay lip service to the word transparency. My team and I are fighting constantly to get access to basic information about what the state is doing. The Official Information Act process is seemingly treated with disdain by many government departments and officials. We’ve had requests for basic information denied on spurious grounds or delayed for ridiculously long periods. Meanwhile, we don’t have access to data on the use of force by our police or on the lockdown hours in our prisons. It’s a waste of our time and resources. This information should be accessible.

There is a lot to unpack in the report. There are big questions for us to consider as a nation. As a human rights organisation, we will be watching when New Zealand appears before the United Nations Committee on the Convention against Torture to respond to the inquiry. We will also be considering the remedies that need to occur following the report findings.

But today, we’re saying thank goodness for civil society. Thank goodness for human rights defenders. And in the name of transparency, the public should be demanding the government enables access to information so we can all get on with doing our jobs to the highest possible standard.

Meg de Ronde is the executive director of Amnesty International Aotearoa New Zealand