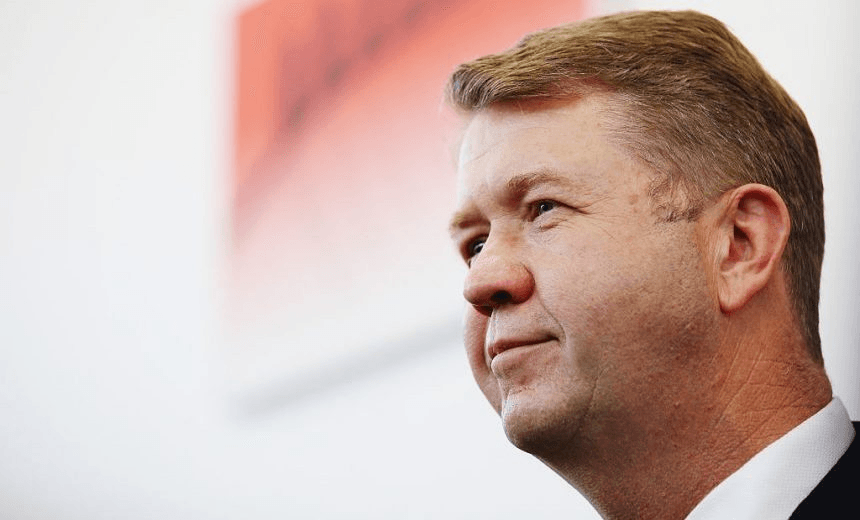

As the polarising former Labour leader announces his parliamentary retirement, Toby Manhire recounts the most vivid Cunliffe memories – from poetry to beach pics to cats

So farewell then, David Cunliffe.

The New Lynn MP and former leader of the Labour Party announced this morning he won’t be standing in next year’s election.

What memories will remain in his political wake? He became an MP since 1999, was a well-regarded minister under Helen Clark and possesses a formidable intellect, but there is no getting around it: he will be chiefly remembered as a destabilising force during David Shearer’s reign and leader of an omnishambolic and divided Labour Party, which culminated in the humiliating defeat at the fever-dream dirty-politics-and-moment-of-truth 2014 election.

As leader, Cunliffe never gained the trust of his caucus. Before and after his election to leader, parliamentary colleagues would privately say he was short on authenticity, loyalty and reliability, though there were relatively few concrete examples they could point to for being brought to states of such palpable despair. The trouble, I was told at the time, was that you could never be sure what he might say when the camera started rolling.

My sense was that he was not as devious or conniving as some painted him. Nor can the blame for all those omnishambles be pinned on him alone. His Achilles heel, it seems to me, was a defunct self-awareness filter; a tendency to believe his own publicity, and to mistake vacuous sloganeering for the inspirational oratory of a bold leader.

But about those memories. What goes on the highlights reel? Which were the Kodak moments? These, for better or worse, are what spring to my mind…

The loyal caucus member

In a November 2012 interview with Guyon Espiner for the Listener, it looked pretty clear Cunliffe was scheming for another go at the Labour leadership, having been beaten in the post-Goff battle by Shearer. What else could you mean by saying things like, “I think that David has got his heart in the right place”?

The most telling passage, however, was this:

Cunliffe knows he is loathed by a good chunk of Labour’s caucus and acknowledges he struggles to contain his ego. He also knows that because his ambition and skill are obvious to others, he must be disciplined about how he portrays himself. He won’t be photographed lying on the grass for this story (fearing it could lead to a ‘snake in the grass’ headline) or initially on the sand (lest he be referred to as ‘all washed up’). He also sees risks with the interview location. He agrees to meet in a café on Ponsonby Rd but then changes his mind. Auckland’s trendy, inner-city suburb might make him look out of touch to ordinary folk. The irony, of course, is that he lives in Herne Bay, an even swankier suburb on target to become the first area in New Zealand where house prices average $2 million.

Cunliffe was furious with the photographer, the brilliant David White, for reporting back their interactions, and let rip next time he saw him.

The poetry

Cunliffe is one of the few who can claim to have been both an acknowledged and unacknowledged legislator of the world. Some of his verse was brought to public attention in another Listener profile, from 2008 by David Fisher.

Settle yourself into a comfy chair and drink it up:

For one short year or two

I suckled you

with potent milk

of truth and learning.

You know my strength

you know my weakness.

They are in you

for I am Harvard

And I am yours.

The conference “coup”

Shortly after the Espiner profile was published, reports of a Cunliffe coup overshadowed everything at the Labour Party conference. Shearer, who produced an impressive leader’s closing speech that launched the KiwiBuild programme that Labour should have been shouting about ever since, was no doubt fuming at the supposed plot against him sucking up all the oxygen. While some felt the coup story was overblown – my own abiding image is Patrick Gower chasing Cunliffe into the lift – it was a turning point for Shearer, partly because of the disruption, and partly because of the change in the leader election rules that divvied up the vote between members, unions, and MPs, as well as making it easier to trigger a contest. The combined upshot was that Cunliffe’s path to power was made considerably smoother.

The leadership campaign launch

In August 2013 Cunliffe officially entered the contest for the role made vacant by Shearer’s resignation. He launched his bid from his constituency office with a passionate, kumbaya-level speech that was part brilliant, part OTT histrionics. It wasn’t helped that there he spoke directly in front of a painting of David Cunliffe.

“I’m sorry for being a man”

The sentiment was laudable enough, especially given the Women’s Refuge meeting setting – and many of the responses (including this) were much more icky than anything about the remark. But – #notallmen! – it was widely perceived as ill-judged, self-aggrandising and/or insincere.

The log

What is it with this guy and sandy pics? The shots of Cunliffe sitting on a log and lying on a beach down the road from his Herne Bay home, apparently contemplating his fraying grip on the leadership, delivered a brutal poignancy. More than any of the squillions of words written that weekend late in September 2014, the images on the Herald front page spoke volumes: the game was up.

The anonymous Twitter attacks

Just to clarify the unravelling, Cunliffe’s wife, with whom he has since separated, set up a Twitter account using a pseudonym/nickname, and attacked the Herald and the Labour caucus’s “anyone but Cunliffe” group. Clayton Cosgrove and Trevor Mallard, for example, were “long past their use-by date”, said one tweet. Another: “The jealousy of Cosgrove and Mallard knows no bounds.”

Cats that look like David Cunliffe

Say what you like about anything else, but without this evocative Tumblr, New Zealand political history would be much the poorer.