Welcome to The Spinoff’s live updates for October 31-November 1. All the latest New Zealand news, updated throughout the day. Reach me on aliceneville@thespinoff.co.nz

1.00pm: Two new Covid-19 cases in managed isolation

There are two new cases of Covid-19 today, both detected in managed isolation during routine testing, says the Ministry of Health. On arrived from Amsterdam via Singapore on October 23, and the other from the UK via Dubai and Malaysia on October 19. Both are now in the Auckland quarantine facility.

New Zealand now has 77 active cases and 1,603 confirmed cases.

Yesterday, there were 4,401 tests for Covid-19, bringing the total number of tests completed to date to 1,101,067.

‘Rubbish bin’ cluster closed

The cluster that began with a person who became symptomatic after leaving managed isolation having returned two negative tests has now closed, as it’s been more than 28 days – the length of two infection cycles – since the last case.

A Ministry of Health investigation found the most likely source of infection to be via a rubbish bin with a lid shared with their neighbour who had developed the infection between the two tests in the facility.

Seven cases are linked to the cluster – six announced as cases in the community (on September 19, 20 and 23) and the seventh (September 9) detected while still in managed isolation, but subsequently linked to the other six cases.

Lessons from this cluster have resulted in changes being made, says the Ministry of Health, including “informing our ongoing auditing and strengthening of our managed isolation procedures and processes”.

12.50pm: For Labour, the drive for cannabis reform is over, but the Greens aren’t giving up

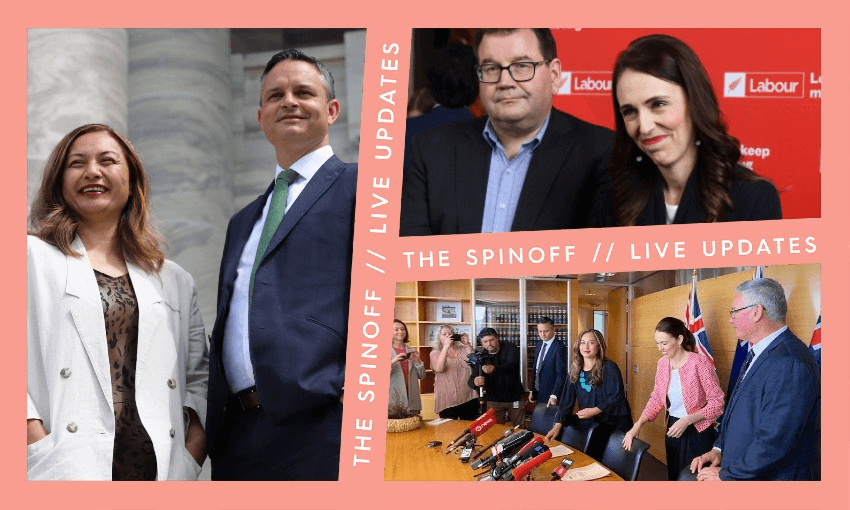

Political editor Justin Giovannetti reports from this morning’s cooperation agreement signing at the Beehive:

The cheap pens with black ink scribbled four names on the Labour-Greens cooperation agreement this morning and New Zealand’s next government is set. It’ll be a Labour majority, with the Greens both helping the government from the inside while prodding it to do better from the outside.

Jacinda Ardern used the word “stability” during her prepared remarks to talk about the agreement and what it ensures: three years of Labour rule. She signed along with deputy Kelvin Davis.

Greens co-leader Marama Davidson, along with James Shaw, took a different approach, twice uttering “we are running out of time” as she briefly talked about the agreement and New Zealand’s future. On climate change and biodiversity, the Greens will remind the government that sand is pouring through the hourglass.

There was one area, drug reform, where the two parties have already shown that they’ll push ahead, while also clashing. The new agreement allows the two parties to disagree publicly and keep working together. “We agree to agree to disagree,” Davidson said. New Zealanders should get used to seeing it.

Speaking with reporters in a small conference room outside the prime minister’s office on the ninth floor of the Beehive, Ardern reiterated Labour’s view that the drive to liberalise cannabis use is over. The Greens have interpreted the narrow loss of the cannabis referendum, based on early results, in very different way. “There has been really positive ground gained in the area of mature and sensible drug reform. The referendum showed a huge increase in support for sensible drug reform law, so again, that’s an area that the Green Party will be able to build consensus and keep working,” said Davidson.

The two parties did agree on pill testing at festivals, something that had been blocked by New Zealand First. While it might be too early to promise it this summer, the leaders bobbed their heads that this can now happen, and soon.

11.15am: Greens sign cooperation agreement with Labour

Green Party co-leaders James Shaw and Marama Davidson have signed the cooperation agreement accepted yesterday in the prime minister’s office on the ninth floor.

In a press conference happening now, Davidson and Shaw played down reported dissatisfaction with the deal among Green members, calling the agreement a “win-win”, saying the fact 85% of delegates voted yes to it showed a “really clear mandate”.

Shaw said he and Davidson are “deeply honoured to be named as ministers”, emphasising the expanded caucus of Green MPs that would have a “valuable and significant contribution to play in parliament”.

In response to reporters’ questions, Davidson said the Greens would continue to speak out on areas outside of their ministerial portfolios or areas of cooperation. Responding to a question from Māori TV about Ihumātao, Davidson said “ka taea e au te tūkaha te kaupapa o Ihumātao” – meaning she will be able to keep pushing hard on the issue. Later in the press conference she quipped, “We already agree to agree to disagree.”

8.40am: The day ahead

The Greens and Labour leaders will be signing the cooperation agreement that was announced yesterday at 11am today at the Beehive. There will be a press conference afterwards and we’ll bring you all the details here.

Saturday, October 31

7.45pm: Greens accept Labour deal

Green Party members have voted to accept the proposed “cooperation agreement” with Labour with reportedly close to 85% support.

A press release from Labour’s chief press secretary Andrew Campbell confirmed the agreement had been accepted, quoting Jacinda Ardern as saying: “Labour won a clear mandate to form a majority government on our own to accelerate our recovery from Covid-19. This agreement respects the mandate voters provided Labour while continuing our cooperative work with the Green Party in areas where they add expertise to build as strong a consensus as possible.

“On election night I said Labour would govern for all of New Zealand and continue to build as much consensus as possible – this agreement achieves that objective.

“We showed in the last government we can work well with the Green Party. On environmental and wellbeing issues there is much we agree on that is good for New Zealand and I want to draw on our shared goals and expertise to keep moving forward with that work.

Greens co-leader Marama Davidson is quoted in the press release as saying: “The Green Party is thrilled to enter into this governing arrangement with Labour, after three years of a constructive confidence and supply relationship.

“We entered into this negotiation hoping to achieve the best outcomes for New Zealand and our planet. This was after a strong campaign where we committed to action on the climate crisis, the biodiversity crisis, and the poverty crisis.

“New Zealanders voted us in to be a productive partner to Labour to ensure we go further and faster on the issues that matter. We will make sure that happens this term.”

Davidson’s co-leader James Shaw, meanwhile, is quoted as saying: “We are very happy to have secured areas of cooperation in achieving the goals of the Zero Carbon Act, protecting our nature, and improving child wellbeing.

“We have a larger caucus this term who are ready to play a constructive role achieving bold action in these areas.

“In the areas of climate change, looking after our natural environment and addressing inequality, there’s no time to waste. Marama will do incredible work rapidly addressing the issues of homelessness and family violence.

“We are proud to have achieved a first in New Zealand political history, where a major party with a clear majority under MMP has agreed to ministerial positions for another party, as well as big areas of cooperation.”

The move has angered former Green MP Sue Bradford, however, who has called it “a sad day for the party”.

https://twitter.com/suebr/status/1322429766075494401?s=20

7.30pm: Green Party members voting on Labour deal now – and it’s close

Green Party delegates are currently voting on whether to accept the proposed “cooperation agreement” with Labour – and sources say it’s close, with many more “no” votes than there were during 2017’s vote on a confidence and supply agreement last election.

Seventy-five percent of the 150 or so delegates who have been on a Zoom call discussing the proposed deal since 4pm must vote yes for it to be accepted by the party.

4.35pm: Both Green co-leaders offered minister roles in deal with Labour

Political editor Justin Giovannetti reports from parliament:

The Greens and Labour have agreed on a “cooperation agreement”, with both Green co-leaders holding ministerial portfolios outside of cabinet. Marama Davidson will be appointed to the position of minister for the prevention of family and sexual violence and associate minister of housing (homelessness), while James Shaw will be appointed to the position of minister of climate change and associate minister for the environment (biodiversity).

Speaking at a press conference at the Beehive now, the prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, has said a coalition “was not in my mind at all”. Today’s deal is also not as strong as the confidence and supply agreement of 2017. She will be announcing cabinet on Monday and ministers will be sworn in on Friday, after which cabinet will meet for the first time.

2017 deal: “Green Party agrees to provide confidence and supply support to a Labour-led government”

2020 deal: “Green Party agrees to support the Labour government by *not opposing* votes on matters of confidence and supply”

Here is the full text of the cooperation agreement:

Cooperation Agreement between the New Zealand Labour Party and the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand

Preamble

- The Green Party commits to supporting the Labour Government to provide stable government for the term of the 53rd Parliament. The parties commit to working in the best interests of New Zealand and New Zealanders, working to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and building and maintaining public confidence in the integrity of Parliament and our democracy.

- This agreement builds on the constructive and enduring working relationship between the two parties. It does this by setting out the arrangements between the parliamentary Labour and Green Parties as they relate to the Ministerial portfolios and areas of policy cooperation set out in this agreement.

Nature of agreement

- The Green Party agrees to support the Labour Government by not opposing votes on matters of confidence and supply for the full term of this Parliament. In addition, the Green Party will support the Labour Government on procedural motions in the House and at Select Committees on the terms set out in this agreement. This will provide New Zealanders with the certainty of a strong, stable Labour Government with support from the Green Party over the next three years.

- The Green Party will determine its own position in relation to any policy or legislative matter not covered by the Ministerial portfolios and areas of cooperation set out in this agreement. Differences of position within such portfolios and areas of cooperation will be managed in accordance with this agreement.

- The Labour Government in turn commits to working constructively with the Green Party to advance the policy goals set out in this agreement, alongside Labour’s policy programme.

Ministerial positions

- The Labour Government’s priorities for this term centre on a COVID-19 recovery plan. This includes the implementation of Labour’s manifesto promises and five point economic plan, with a focus on investing in our people and preparing for the future.

- The Green Party’s aspirations include enabling a Just Transition to a zero-carbon economy; supporting equity, compassion and inclusive communities; ensuring ecosystems, indigenous species and their habitats thrive; and cultivating a flourishing democracy founded on Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

- This agreement supports the advancement of these priorities by allocating portfolios and establishing areas of cooperation that are consistent with the direction and goals of the Labour Government, as well as contributing to addressing the Green Party’s aspirations.

- The Green Party will hold the following portfolios outside of Cabinet:

- Marama Davidson will be appointed to the position of Minister for the Prevention of Family and Sexual Violence and Associate Minister of Housing (Homelessness).

- Hon James Shaw will be appointed to the position of Minister of Climate Change and Associate Minister for the Environment (Biodiversity).

- The Minister for the Prevention of Family and Sexual Violence will be the lead Minister for the whole of government response on family and sexual violence with the mandate to coordinate Budget bids in this area. The Minister will also be a member of the ad hoc Ministerial group on the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy.

- These Ministerial portfolios also reflect areas where Green Party expertise provides a valuable contribution to the Labour Government.

- Ministers from the Green Party will attend Cabinet Committees for items relevant to their portfolios and receive Cabinet Papers relevant to their portfolios, as provided for in the Cabinet Manual.

- In addition, the Labour Party will support the nomination of a Green Party Member of Parliament to be the Chair of a Select Committee, as well as a Green Party Member of Parliament in the role of Deputy Chair of an additional Select Committee.

Areas of cooperation

- The parties will cooperate on agreed areas where the Labour and Green Parties have common goals:

– Achieving the purpose and goals of the Zero Carbon Act through decarbonising public transport, decarbonising the public sector, increasing the uptake of zero-emission vehicles, introducing clean car standards, and supporting the use of renewable energy for industrial heat.

– Protecting our environment and biodiversity through working to achieve the outcomes of Te Mana o te Taiao – Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2020, protecting Kauri, building on pest management programmes, and taking action to minimise waste and problem plastics.

– Improving child wellbeing and marginalised communities through action on homelessness, warmer homes, and child and youth mental health. - These areas of cooperation reflect common goals between the Labour and Green Parties, and represent areas where the policy and experience of the Green Party provides a positive contribution to the Labour Government.

- The Labour and Green Parties will work together in good faith and cooperate with each other in respect of executive and Parliamentary activities to advance these shared goals, including any public statements. The Prime Minister’s letters of expectations to Ministers will reflect the areas of policy cooperation and consultation processes required.

- Beyond these stated areas of cooperation, it is also the Government’s intention to work with political parties from across Parliament (including the opposition) on issues that affect our democracy, including the Electoral Commission’s 2012 recommended changes to MMP, electoral finance law, and the length of the Parliamentary term.

Consultation

- On the areas of cooperation set out in this agreement, or other matters as agreed, the parties commit to undertaking political consultation between the responsible Minister and the appropriate spokesperson. This process will also apply to Green Party Ministerial portfolio matters.

- This process, which will be agreed between the parties and set out in a Cabinet Office Circular, will cover:

– the initial policy development, including access to relevant papers and drafts of legislation,

– the development of Cabinet Papers,

– the public communication of the policy to acknowledge the role of the Green Party. - The Labour Government will also brief the Green Party on:

– the broad outline of the legislative programme,

– broad Budget parameters and process. - Outside of the areas specified in this agreement, there will be no requirement for consultation, but this could happen on a case by case basis.

- Where there has been full participation in the development of a policy initiative and that participation has led to an agreed position, it is expected that both parties to this agreement will publicly support the process and outcome. This does not prevent the parties from noting where the agreed position deviates from their stated policy.

Relationship between the parties

- The Labour and Green Parties will cooperate with each other with mutual respect on the areas set out in this agreement. Cooperation will include joint announcements relating to areas of policy cooperation.

- The Leader of the Labour Party and the Green Party Co-leaders will meet every six weeks to monitor progress against the areas of cooperation set out in this agreement. The Chiefs of Staff will meet regularly.

- The parties agree that any concerns will be raised in confidence as early as possible and in good faith, between the Prime Minister’s Office and the Office of the Co-leaders of the Green Party. Matters can be escalated to the Chiefs of Staff, and then Party leaders, as required.

- The parties may establish a process in order to maintain different public positions on the areas of cooperation. The parties agree that matters of differentiation will be dealt with on a ‘no surprises’ basis.

- This agreement will evolve as the term of Government progresses, including through opening up potential additional areas of cooperation. Any additional areas of cooperation will be agreed to between the Party leaders and given effect by a letter from the Prime Minister to the relevant Minister.

Cabinet Manual

- Green Party Ministers agree to be bound by the Cabinet Manual in the exercise of Ministerial Responsibilities, and in particular, agree to be bound by the provisions in the Cabinet Manual on conduct, public duty, and personal interests of Ministers.

Collective responsibility

- Ministers from the Green Party agree to be bound by collective responsibility in relation to their Ministerial portfolios. When speaking within portfolio responsibilities, they will speak for the Government representing the Government’s position in relation to those responsibilities.

- In accordance with the Cabinet Manual, Ministers from the Green Party must support and implement Cabinet decisions in their portfolio areas. However, Ministers from the Green Party will not be restricted from noting where that policy may deviate from the Green Party policy on an issue. If this is required, it may be noted in the Cabinet minute that on a key issue, the Green Party position differs from the Cabinet decision.

- When Ministers from the Green Party are speaking about matters outside of their portfolio responsibilities, they may speak as the Co-leader of the Green Party or as a Member of Parliament.

- Agree to disagree provisions of the Cabinet Manual will be applied as necessary.

Confidentiality

- Ministers from the Green Party will be bound by the principle of Cabinet confidentiality, as set out in the Cabinet Manual.

- Where Cabinet papers or other briefings are provided to the Green Party, or where the Green Party is involved in consultation on legislation, policy or budgetary matters, all such material and discussions shall be confidential unless otherwise agreed.

- In the event that Government or Cabinet papers are provided to the Green Party for the purposes of political consultation they shall be provided to a designated person with the office of the Green Party, who will take responsibility for ensuring they are treated with the appropriate degree of confidentiality.

- Once confidential information is in the public domain, both parties are able to make comment on the information, subject to any constraints required by collective responsibility or this agreement.

Management of Parliamentary activities

- Both parties commit to a ‘no surprises’ approach for House and Select Committee business. Protocols will be established for managing this.

- The Leader of the House will keep the Green Party informed about the House programme in advance of each sitting session.

- Consultation on legislation outside of the scope of this agreement will be conducted on a case by case basis. The Green Party will consider its position on each Bill in good faith and advise the relevant Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office.

- The Labour and Green Parties agree to a ‘no surprises’ approach to new Members’ Bills. However, neither party is under any obligation to support the other party’s Members’ Bills.

- The Green Party will support the Government on procedural motions in the House and in Select Committees, subject to consultation being undertaken. This excludes urgency, which will be negotiated on a case by case basis. The Labour Party Whip and Green Party Musterer will establish protocols to ensure these processes work effectively to meet the expectations of both parties.

- The Green Party undertakes to keep full voting numbers present whenever the House is sitting where the Green Party has committed to support the Labour Government and on matters of confidence and supply. The Green Party also undertakes to keep full voting numbers in Select Committee, unless otherwise agreed.

4.00pm: Green Party delegates to vote on proposed deal with Labour

A proposed deal with Labour will be put to 150 Green Party delegates via a Zoom meeting at 4pm, and 75% of them must support it for the deal to be accepted. The Spinoff understands that members aren’t happy they’re finding out about the deal only half an hour before the prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, is set to announce it publicly. “So much for transparency,” said one.

It’s believed Greens co-leader James Shaw has been offered the climate change portfolio, while his co-leader Marama Davidson may get an undersecretary role, along with Green MP Jan Logie.

Meanwhile, Stuff political reporter Henry Cooke has tweeted this:

And Ardern has posted on Instagram about working out her cabinet lineup, which will be announced next week.

Read our political editor Justin Giovannetti’s “what to expect” explainer here.

1.00pm: Seven new cases of Covid-19 in MIQ

There are seven cases of Covid-19 to report from managed isolation in New Zealand today, and no new community cases, the Ministry of Health has announced. One case arrived from the United States on October 26, one arrived from the Ukraine on October 26, two arrived from Qatar on October 27, one arrived from Dubai on October 28, and two arrived from Qatar on October 29.

All cases were detected during routine isolation and testing processes and are now at the Auckland quarantine facility. New Zealand’s total number of active cases is now 75 and our total number of confirmed cases is now 1,601.

Yesterday laboratories completed 5,964 tests for Covid-19, bringing the total number of tests completed to date to 1,096,666.

Japan case

The case of a New Zealand child who returned a weak positive Covid-19 test on their arrival in Japan on October 23 is now closed, says the ministry. “Further testing of the child, their household and contacts have all revealed negative test results. This public health investigation has also investigated the tests and possible historical exposures.

“It has been determined that it was not the result of a recent Covid-19 infection. There is no ongoing risk for New Zealand and the case is now closed.”

International mariners in Christchurch

Day 15 testing is being carried out this weekend of all group members who are not already confirmed cases, says the ministry. “All those who meet our low risk indicators, which include those who’ve recovered or have returned consistently negative test results throughout their stay, will be eligible to leave managed isolation from next Tuesday 3 November.”

8.00am: We could have a new government this weekend

While yesterday was all about the referendum results, today our attention turns to the little matter of a new government as negotiations between Labour and the Greens reach their conclusion.

At 4pm, Green Party members will start debating whether to accept what’s been negotiated via a Zoom meeting.

At 4.30pm, the prime minister will unveil the agreement at a press conference. At some point this evening, the results of the Greens’ discussions will come out.

Tomorrow, if the Greens approve the agreement, there will be a signing ceremony and press conference with Green and Labour leaders at 10am.

Our political editor Justin Giovannetti has written more about what to expect here. He’ll be there for the action at parliament this weekend, and we’ll be bringing you updates as they happen right here.

7.30am: Yesterday’s headlines

Preliminary referendum results revealed 65.2% voted in favour of the End of Life Choice Act, while 53.1% voted no to cannabis legalisation.

There was one new case of Covid-19 detected in MIQ – a member of the international mariners group in Christchurch.

The health minister revealed new rules for Covid-19 testing of international maritime crews arriving in New Zealand.