As it gears up for as many as three referendums next year, NZ should take care not to ignore the mistakes of Brexit, writes Christian Smith.

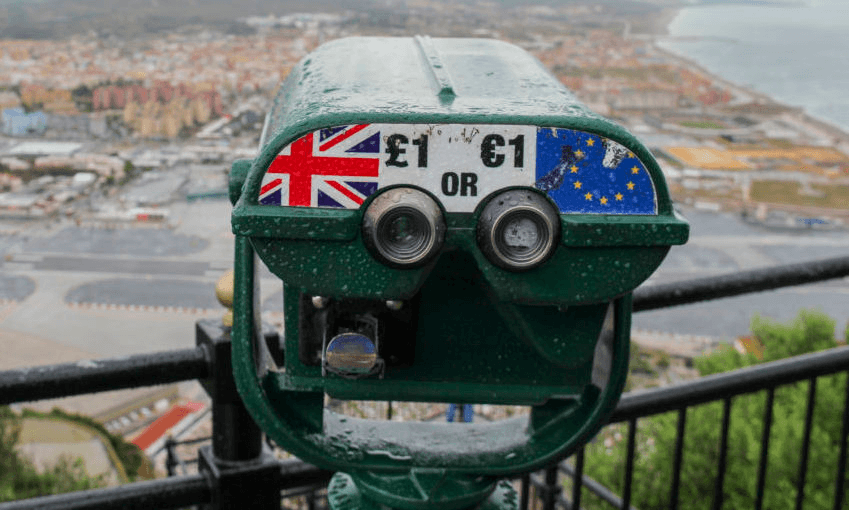

Brexit is the problem that every other country in the world is glad not to have. For New Zealanders, it may seem a distant curiosity, relevant only to our future trade. But it’s also a phenomenon that reveals much about the nature of modern democracies. With potentially three referendums proposed for New Zealand in 2020 – on cannabis, euthanasia, and MMP thresholds – the Brexit referendum offers crucial lessons on how not to run a modern referendum.

Beware the ‘post-truth’ pandemic

Post-truth politics is the idea that arguments are not won on the basis of objective facts but on emotional appeal and by reinforcing pre-existing beliefs. In the lead up to the Brexit referendum, both sides were blameworthy of such exploits. The quality of the discourse was, at best, underwhelming and since the referendum, both sides have been accused of telling outright lies.

The Remain campaign stuck rigidly to advocating for the economic benefits of staying in the EU, and the potential disaster that leaving might create (what Brexiteers labelled ‘Project Fear’). Brexit campaigners played on immigration concerns and the idea that Britain needed to ‘take back control’. Each side also relied on completely contradictory statistics to support their campaigns. The cannabis and euthanasia referendums provide fertile ground for post-truth politics. The debates for both easily lend themselves to personal anecdotes and emotional appeal. This is not to say that such appeals are a new or a bad thing. People often vote with their hearts rather than their heads. The difference is that in the past it was much easier to sift the truth from the lies. Emotional appeals were linked to facts, and if they weren’t, they were called out and dismissed. In any event, such tactics should also not be allowed to distract from the facts of the debate.

The danger is that voters simply choose to believe the evidence that supports their pre-existing beliefs. Last October on TVNZ 1’s Q + A programme, the Green’s Chlöe Swarbrick debated Bob McCoskrie from Family First on legalising cannabis. At one point, they began throwing different studies at each other which made entirely opposing claims about the effects of legalising cannabis. This perfectly highlights the issue that faced the British, and will face New Zealanders next year: how can voters make an informed decision when the evidence appears to point in two different directions? There’s no easy solution to this issue. With an oversaturated internet, the loss of authority of traditional information sources is one of the principal issues facing western democracies.

Make the terms clear

The post-truth peril is only encouraged when there is ambiguity about what is being voted on. The political chaos witnessed in the UK, with the debate around soft vs hard vs no-deal Brexits, and endless variations thereof, stems from the lack of specificity in what was put to voters on the ballot. It’s encouraging, at least, that Andrew Little has indicated that legislation will be in place for cannabis reform so that voters know exactly what’s at stake.

Keep it above the belt

For better or worse, we live in the age of social media comments, and the abandonment of basic courtesy that comes with them. There is a fair argument that this toxic dialogue has emerged into the real world and is increasingly apparent in political discourse. Likewise, it’s becoming a cliché that we are living in a polarised world where one must stick to his or her party line, where compromise is a dirty word, and where the opposition’s views are not only wrong but morally repugnant.

The debate leading up to the Brexit vote, and the rhetoric since, is a cause of that cliché. The campaign was exceptionally divisive. Many Remainers quickly tarnished Leavers as stupid racists, yearning after a bygone Britain. Conversely, numerous Leavers classed Remainers as selfish, undemocratic and out of touch elites. It’s difficult to underestimate just how divisive Brexit has been for Britain, and the ugly nature of the campaign reflected that.

The Brexit referendum asked a defining question about the UK’s future that went to the very heart of British society. Admittedly, next year’s referendums are not so fundamental. Similarly, New Zealand’s society is in far better shape than the UK’s was in June 2016. Brexit did not cause the deep divisions in that society, it exposed them.

Despite this, the issues up for debate are still highly divisive. At the very least, one asks a question about what we consider to be the meaning of the sanctity of life. We have also already had a taste of Brexit nastiness with some of the debate around drug law reform.

The lesson we should take from Brexit here is not revolutionary: let’s try to keep it civil. It’s the same rule that democratic politics has (largely) managed to follow for a century, but that we seem to have forgotten. An ugly campaign can harm a country for years to come. We should strive to avoid the condescension, the name calling, and the stereotyping, and try to remember that the reason we’re having these debates is because there are valid points on both sides. One of the sad facts about Brexit was that people were so quick to decry and brand those who disagreed with them that they didn’t take the time to understand the reasons behind their point of view.

Don’t rush it

With any referendum, the public needs a decent opportunity to come to terms with the issues at hand. While the British public knew since 2015 that there would be a Brexit referendum, the new arrangements for Britain’s membership of the EU (which British Prime Minister David Cameron renegotiated) and the date on which the referendum was to be held were only announced four months before the ballot. This timespan has been criticised as too short. In its report following the Brexit referendum, the UK’s Electoral Reform Society argues that all referendums should have a minimum six-month regulated campaign period.

Andrew Little has announced that the cannabis referendum will not take place until the 2020 general election, and the debate is already under way. This is good.

However, it is undecided whether two more referendums will be held on the same ballot. This would be bad. In fact, it would be absurd. The suggestion that in the lead up to the general election next year we will also be able to have a thorough, engaged debate about what are three relatively serious issues is ridiculous. It’s never been done before in New Zealand. Of course, party and coalition politics is rearing its head here, and the end result will be a watered down, unsatisfactory debate on all four polls. This is not to denigrate the public in any way, but it is not reasonable to expect the electorate to be able to thoroughly engage in these issues in such a timeframe.

Democracy only works when the loser accepts the result. Accordingly, it’s not just democratic to ensure a vote is fair, it’s practical too. If a vote loses legitimacy, it can create the kind of backlash Britain is currently experiencing. Our stakes may not be as high, but the principle is the same.