If parliament is a house of representatives, how representative has its most powerful members been? Lawyer Faisal Halabi crunches the numbers.

The cabinet is a key mechanism through which the governing by our elected representatives is done. It’s the highest point of the executive arm of government where discussions and decisions are made on issues such as health, education and the economy. Current political dreamboat Justin Trudeau made Canadian history when, in 2015, he installed a cabinet consisting of an equal number of men and women – an appreciation of the importance of representation in relation cabinet’s role in governing.

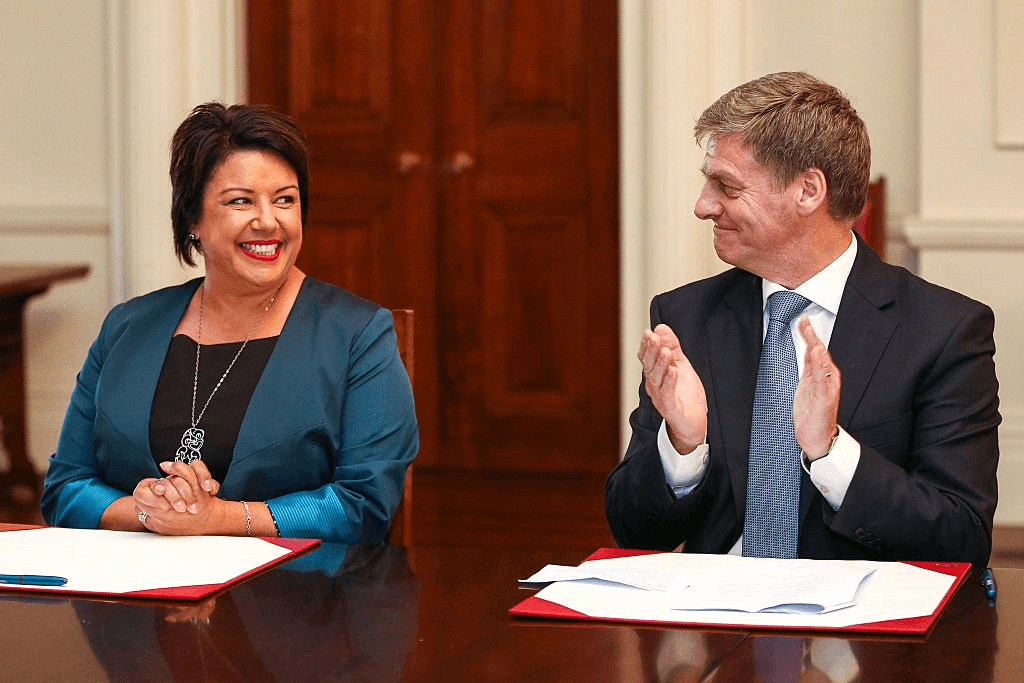

I’m not sure that there’ll ever be enough Young Nat memes to give Bill English the international profile Trudeau currently enjoys, but that’s not important. What is important is to take note of who sat in our most recent cabinet, who did so previously, and what observations can be made about this bunch.

Gender: There were seven women and 13 men in our most recent cabinet

It wasn’t so long ago that the cabinet table was a striking example of the glass ceiling in action. In the Shipley and Bolger days, there was only one woman in cabinet (Shipley herself), although Georgina te Heuheu entered the ranks in the final Shipley cabinet. A run through the Key and Clark cabinets illustrates that overall, the number of women in cabinet was consistently about half the number it is now. In Clark’s final cabinet, for example, there were four women (Clark, Annette King, Ruth Dyson and Nanaia Mahuta). So over the past 20 years, the number of women in cabinet has risen very slowly – making English’s seven an all-time peak. In the cabinet world, slow and steady wins the patriarchy race.

Careers and work experience: politicians are mainly lifers

In the current cabinet, one-third of ministers have work experience in public office before entering parliament. The most common background of those from the private sector? Law.

A handful of the 20 ministers have bespoke backgrounds: before she launched her political career, Maggie Barry was…Maggie Barry.

An almost-extinct variable in the work experience category becomes evident when comparing recent cabinets to earlier ones (see all the source data used in the following graphs here). For a nation that prides itself on stomping around in our gumboots and the no. 8 wire mentality, it’s clear that those in the highest spots of executive office have very little to do with that. Granted, current Speaker of the House and former Cabinet minister David Carter had a career in farming sheep and cattle.

Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away known as the Muldoon-era National cabinet, about a quarter had work experience in blue-collar jobs and farming or fisheries. That contrasts to the Palmer-era Labour cabinet, where a majority had work experience as university professors or schoolteachers.

(see the data used in these graphs here)

The correlation between experience and portfolio

Closely related to the variable of career and work experience is the correlation between each minister’s portfolio and the experience they bring. That correlation is there in English’s cabinet. Overall, every minister in cabinet can safely say that they have experience that is relevant to the portfolio they hold.

This correlation between career/work experience and each minister’s portfolio has generally increased over time, despite some dips and dizzyingly clear contrasts. For example, in Palmer’s cabinet, almost every minister had some correlation between their portfolio and work experience prior, which contrasts to Bolger’s cabinet in the cycle after, where almost every minister did not.

Reasons for leaving

The ghosts of cabinet ministers past from this current cabinet adds another dynamic. Their reasons for leaving include the benign (Simon Power; resigned and entered the private sector), controversial (Pansy Wong; misuse of Parliamentary travel allowance), and to take on roles in other, considerably more flashy offices (Tim Groser; New Zealand Ambassador to the United States). So, it’s safe to say you’ll only be looking to leave cabinet if you’ve got an apartment with skyline views in New York, or you’ve committed a no-no.

Roles subsequent to cabinet

Regardless of why you leave, the occupations of ministers subsequent to leaving cabinet have been consistent over the years: later appointments to ministerial positions and public sector employment. Only a minority of cabinet ministers in the past have entered senior roles in the private sector. Perhaps an observation of this may be that the cabinet position has instilled in them a long-term appreciation of public service. Or perhaps the private sector just ain’t hiring cabinet ministers.

Marriage and children

Being a cabinet minister is a very busy role, but one must always find a healthy work-life balance. Most cabinet ministers, from Norman Kirk to the present, have been married. In fact, it’s not until more recent cabinets that we saw a change: in Key’s first cabinet, two ministers were single and two were divorcees. Some ministers have been even busier: English is high up in the spectrum of cabinet ministers with children, with six. Jim Bolger is the clear winner though with nine.

A matter of degrees

Another almost-extinct variable in the makeup of our cabinet ministers appears in the qualifications category. Today, the majority of cabinet ministers hold a tertiary qualification. Anne Tolley, ever the tech guru, is the closest to an exception in the most recent cabinet – she holds a diploma in computer programming.

In the years of Norman Kirk’s cabinet, the number of ministers with a tertiary qualification was less than half – including Kirk himself, who did not complete his secondary schooling. The other half of Kirk’s cabinet came into the now-extinct variable of a secondary school graduation being their highest qualification. The number of ministers in that category carried on into the Muldoon cabinet, with almost half having that as their highest achievement.

However, by the Lange years, almost all of cabinet held a tertiary qualification. In Shipley’s cabinet, all but one cabinet minister held a tertiary qualification (Tau Henare).

If we were to come back to the premise of what the cabinet represents, then let’s ask ourselves a question: can it be said that today’s cabinet goes towards reflecting the diversity of 2017 New Zealand, versus the parallel of what Muldoon’s cabinet meant to New Zealand in the late ‘70s? The answer isn’t exactly a yes, but it’s closer. There are more women, there are more Pasifika people, and there is greater Māori representation.

But perhaps there is an argument that cabinet remains a reflection of New Zealand’s political elite. Actually, remove that ‘perhaps’ and replace it with a ‘definitely’. The majority of cabinet is now university educated, middle class men. And while it has a greater ethnic and gender diversity than years gone by, in other areas, there has been a swing away from a representative cross-section of New Zealand. We will have to see which way Winston swings to know whether the trend continues.