The government wants to make it easier to remove protections on heritage buildings – but more change is needed.

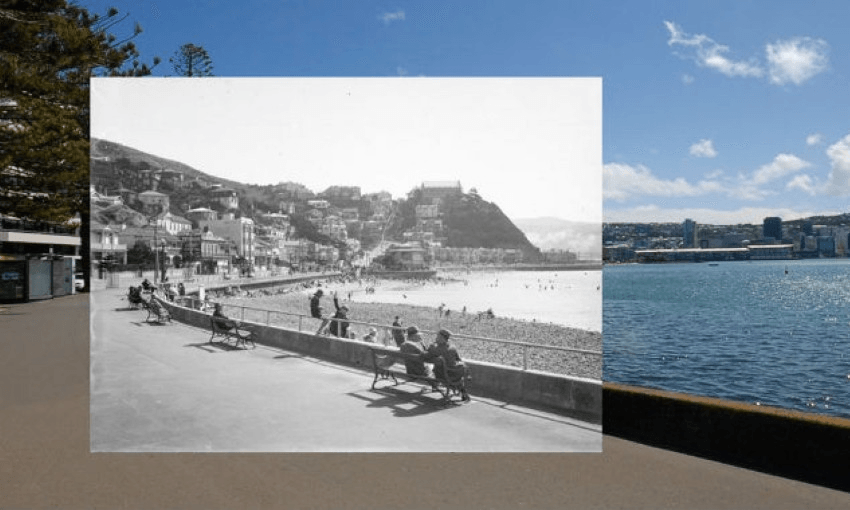

The Oriental Parade sea wall is a long, concrete barrier that curves around the stretch of Oriental Bay. It’s a critical piece of infrastructure, first built in the 1920s to protect the adjacent houses and roads from storm surges. Its purpose is just as vital today – arguably more so, given the threat of rising sea levels due to climate change. But there’s a problem: the sea wall is subject to heritage protections, because it is recognised as “an important early civil engineering structure” with “a distinctive form and profile.”

Those protections mean that any maintenance on the sea wall must use like-for-like materials in a way that recreates the original appearance, or requires an expensive and lengthy resource consent application. At a practical level, that means repairs are more difficult and expensive than they would otherwise need to be. That costs the council (and ratepayers) money.

The Oriental Bay sea wall is not the only piece of heritage-protected infrastructure in Wellington. There’s also the Evans Bay sea wall, the Lyall Bay sea wall, the Island Bay sea wall, the Seatoun Tunnel, the Karori Tunnel, the Northland Tunnel, the Hataitai Bus Tunnel, the Kelburn Viaduct and the retaining wall on Carlton Gore Road.

All of these structures were significant engineering achievements at their time and are worth acknowledging. But they’re all still in active use, and to most people, their value is practical, not historic or aesthetic. The heritage protections are a hindrance to their core purpose.

Wellington is not the only city facing overly onerous heritage restrictions, but the issue is particularly salient in the capital because it has a greater number of heritage buildings (575 on the current council register), many of which have suffered earthquake damage.

Wellington City Council has spent $380 million strengthening its heritage buildings over the past five years, mostly on the central library and town hall. Other publicly owned heritage buildings, such as the Gordon Wilson flats and Dixon St flats, have become prominent ruins. Several private building owners want their heritage protections removed so they can do simple renovations. Oh, and the city now has heritage protections on a rusty oil tank.

Wellington City councillor Ben McNulty has been leading the charge on heritage reform. During last year’s District Plan debate, he attempted to remove the heritage listings from 10 buildings (all of which were requested by the owners), including the Gordon Wilson flats and the rusty oil tank. After that move failed for process reasons, McNulty and Wellington mayor Tory Whanau wrote a letter to minister for RMA reform Chris Bishop asking for new legal powers to remove heritage protections.

“The decisions made by previous generations of heritage advocates are resulting in expensive legacy issues. Whilst the Council technically can remove properties from heritage listing under current legislative conditions, in practice it is an uncertain and risky pathway to delist a heritage building,” McNulty and Whanau wrote.

The protection process

There’s a common misconception that Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga is responsible for imposing heritage protections – but that’s not quite right. Heritage New Zealand identifies buildings for the national heritage list and advocates for their protection, but the actual legal restrictions kick in once a council “schedules” the building in its District Plan. Many councils also employ in-house heritage experts to identify sites of local significance that aren’t recognised by Heritage New Zealand. Most of Wellington’s heritage sea walls fall into this category.

Giving a building heritage protection is a relatively simple process and, in the past, it has been mostly uncontroversial. It’s only years later, when the building owner wants to renovate or demolish it, that the heritage protections become a problem. But once a council has made a heritage decision, undoing it isn’t so easy.

Removing heritage protections requires a change to the District Plan, which involves an extensive process of public hearings and can be challenged in the environment court. Once a building has been heritage-scheduled by a council, its protection becomes a “matter of national importance” under the Resource Management Act. This is an extremely high bar which planners and courts must consider and often trumps all other considerations.

What could – and should – change

Bishop has proposed creating a streamlined process to allow councils to remove heritage protections by a simple majority vote. This would be much faster and harder to challenge than the current system, as it would leave the final decision in the hands of the environment minister rather than the courts.

Wellington City Council supported the streamlined delisting process in its submission on the RMA reform bill. Heritage New Zealand opposed the change, with chief executive Andrew Coleman writing that “there is insufficient evidence to justify them and they have not been fully worked through”.

The streamlined process would help to address some of the more egregious issues with the heritage regime, but it’s really just a stopgap measure. Both the council and Heritage New Zealand agree that more is needed.

The big issue that needs to be addressed is that pesky matter of “national importance”. See, heritage isn’t the only thing considered to be of national importance under the RMA. There’s also: coastal environments, lakes and rivers, outstanding natural landscapes, areas of significant native bush, Māori connections to ancestral lands and water, protected customary rights, and risks of natural hazards.

Many other relevant matters aren’t listed, but might be locally important on any given decision: urban growth, access to housing, costs of repairs, safety risks, property rights, and, in the case of the heritage sea walls and tunnels, the ability to maintain and operate essential infrastructure.

Under the current law, there is no guidance for how planners and courts should weigh up these competing matters. This means we end up in situations like the Gordon Wilson flats, where there are many obvious negatives of letting a decaying ruin continue to stand, but its heritage protections leave it stuck in a quagmire. There needs to be some kind of government-level directive which makes it clearer how each other those matters should be weighed against each other.

Heritage protections aren’t an inherently bad thing. The problem with the current system is that they are too blunt and inflexible. We can protect the buildings and structures that we collectively value, but we need to acknowledge that those protections have trade-offs – and sometimes, those trade-offs simply aren’t worth it.