When rural land gets rezoned for home building, developers make a killing – all while local workers find it harder and harder to find affordable housing. Enter ‘inclusionary zoning’, a wealth redistribution policy that could be coming to a council near you soon.

This article was first published in Bernard Hickey’s newsletter The Kākā.

How can Aotearoa redistribute the massive wealth gains on land in order to help solve our housing affordability, poverty and climate crises? It’s a debate that appears frozen for now.

The prime minister’s “never in my political lifetime” stance on wealth and capital gains taxes, the Greens’ lack of leverage over Labour, and National and Act’s long-held opposition to capital or land taxes have closed down the Overton Window on the issue. The debate being reopened in the foreseeable future depends largely on whether The Opportunities Party and Te Pāti Māori get enough (or any) leverage in government-forming negotiations to force the window back open. But even that remains impossible while Jacinda Ardern remains Labour leader and sticks to ruling out taxes on wealth and capital gains, as she did at the 2020 election.

Given the current polls currently show voters want a National/Act government in its own right, the chances are fading for any sort of centralised attempt to begin wealth redistribution and solve the funding blockages in local government.

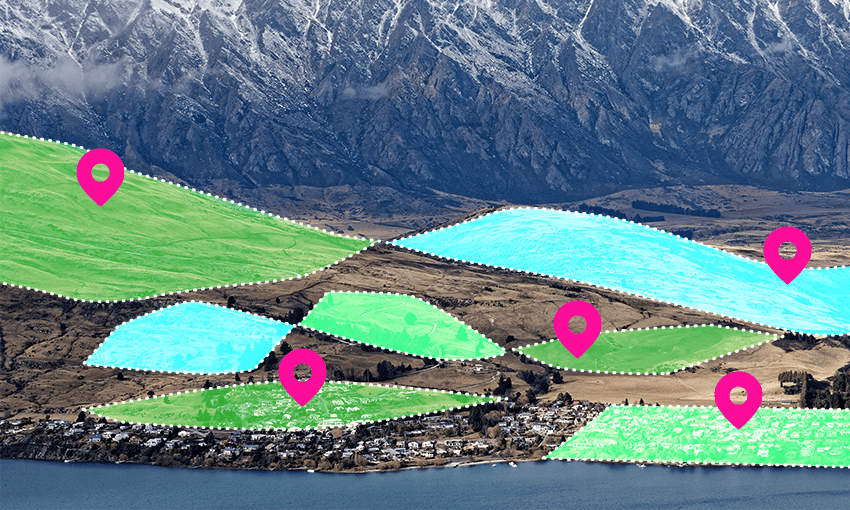

But there is a glimmer of hope emerging at the local level, led by the Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust and its founder, the Queenstown Lakes District Council, which have been quietly operating an inclusionary zoning system since 2003. Inclusionary zoning is a non-threatening phrase to describe landowners benefiting from a zoning change being required to hand over a certain percentage of the sub-divided land, or a monetary equivalent, to a community housing provider in order to build affordably priced homes for rent or sale. It is a common practice in the United States, the UK and Australia.

It was introduced to New Zealand in 2003 by a young American town planner working for the Queenstown Lakes District Council named Scott Figenshow, who went onto become the long-serving CEO of Community Housing Aotearoa. Having seen how effective the practice was in the United States, Figenshow ensured the Jack’s Point development was required to put aside around 5% of the rezoned land value for a Community Housing Trust developed specifically for the purpose by the council.

This practice has been kept going since then, helping to fund the building of homes for 244 families in Queenstown. Inclusionary zoning, or “inclusionary housing” as the trust now calls it, has already built 109 homes from the 5% contributions of land or money by developers, with a further 215 in planning or building stages across the district.

The council decided to formalise the practice in its new district plan and put a proposal out for consultation earlier this year. However, the proposal as it stands would actually expand it to include “Mum and Dad” redevelopments of large sections into two or three plots for infill housing. Contributions would range from 1% to 5% and also include the triggering of a new contribution when an empty plot is built on.

‘Don’t tax my land. Tax someone and something else.’

That’s when the trouble started. The issue was picked up in the local election campaign, with some calling the practice a new tax. Here’s an example of the reaction from Kinloch Wilderness Retreat owner John Glover, quoted in Crux:

“Using the RMA to deliver inclusionary zoning, which is basically a tax, is really quite perverse, and it’s actually probably stretching the scope of the RMA…the revenue raising path in the RMA is about cost recovery. How does that help with affordability of housing?

“You’re not proposing to tax the businesses and the tourism operators…whose rapid growth in the district has been a significant factor underlying the housing shortage.”

Essentially, land owners, fearing some of their unearned gains were about to be taken away, said other people and other activities should be taxed, rather than their capital gains on land values generated by rezoning decisions.

They could also see the potential for the practice to spread. One councillor, Nikki Gladding, even opposed the plan on the grounds it would cost a lot of money to defend in the courts once developers challenged it:

“It’s going to go through the courts and we won’t get any money out of this, if we ever do, for five, six years…and it’s going to take all that time and money to get there.”

Understanding the sensitivities, the housing trust has made a submission to the district plan suggesting paring the inclusionary housing contributions back to brand-new and full scale developments.

The council is now in the final stages of considering the submissions and is expected to vote on the final form of inclusionary housing/zoning in the coming months.

Why including inclusionary zoning feels so dangerous (and hopeful)

Why is everyone being so sensitive about a practice commonly used overseas? Because it feels like the thin end of a wedge that might touch the biggest wedge of wealth of all: unearned gains on private land values driven by rezoning and public infrastructure investment.

We are the only developed economy in the world that does not tax this wealth. No wonder the owners of that wealth feel a little nervous.

Being taxed on earnings is painful. But being taxed on a lottery win feels like more like theft, given the government is benefiting from the good fortune for an individual. There’s something in that process of taxing a lottery win that seems to trigger a particular level of outrage.

Ideas like inclusionary zoning represent a profound threat to New Zealand’s traditional approach to wealth-building, based as it is on rising land values created out of land use restrictions, infrastructure under-spending and falling interest rates. And that’s all before we even get to the original provenance of the land and how it came to owned by settler families and farmers. Deep down, most land owners know they don’t deserve their huge profits and that if justice was done, that unearned wealth would be redistributed to those who owned the land to begin with, and to those who have to rent the land and service the landlord/rentier class.

Why the Queenstown situation matters so much

The reason the Queenstown example is so important is that the current RMA reforms could be the vehicle for wider adoption of the Queenstown way. The reforms could see every district plan rewritten to include inclusionary zoning, effectively bypassing the frozen debate at the central government level.

Why shouldn’t every district plan include inclusionary zoning? Lots of councils are watching Queenstown closely and the RMA rewrites look to be perfect opportunities to adopt the practice more widely.

Two podcasts about inclusionary zoning

I spoke to the Queenstown District Housing Trust CEO Julie Scott about the concept for my Spinoff podcast, When the Facts Change, a couple of weeks ago.

Also, on her podcast Right at Home, Community Housing Aotearoa CEO Vic Crockford talked with her predecessor Scott Figenshow and Roy Thompson, co-founder and managing director of New Ground Capital, about the use of inclusionary zoning.