As the referendum approaches and the road toll rises, the government is under pressure to deal with drug testing, but it’s more complicated than it first appears, writes Don Rowe.

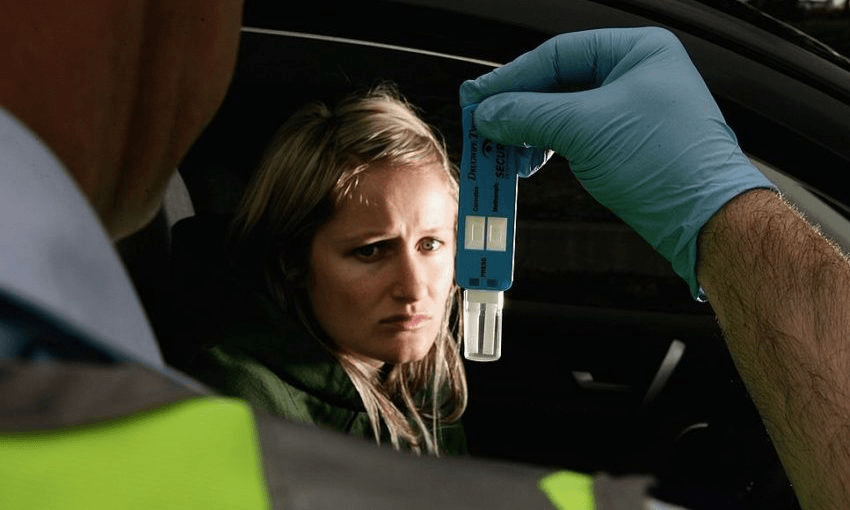

The government has announced a public consultation on drugged driver testing following rising road tolls, an impending referendum, and intense pressure from an opposition desperate to portray the coalition as inept on the issue. It all focuses attention to the gordian knot of how to actually test for substances like marijuana, synthetics and prescription medication.

In an encouraging move for reform advocates, the discussion document, released yesterday by associate minister of transport Julie Anne Genter and minister of police Stuart Nash, openly acknowledges there is no “clear linear relationship” between the presence of a drug and potential impairment. But while Nash assured media in Wellington government had an obligation to give police the tools they need, there is currently no magic bullet for detecting intoxication, as Chlöe Swarbrick said on Q&A Monday.

“We currently don’t have the perfect technological solution,” the Green MP said. “What we do have is old-school impairment testing.”

The NZ Drug Foundation’s Ross Bell said the science backs Swarbrick’s position. The most effective way to find out if someone is high, Bell says, is as simple as making them walk in a straight line. But the issue has become a public battleground, with National attempting to take the moral high ground by voicing support for grieving families who have called for legislation bill mandating random roadside drug testing.

Last week, bereaved parents delivered a petition to parliament demanding the government institute testing nationwide. The petition was received by Nick Smith, who was later declined leave to table a bill proposing roadside testing, and eventually named and suspended after accusing speaker Trevor Mallard of being soft on drugs. Smith’s position is also supported by the AA, which reports 95% of their members in favour.

Logan Porteous, who lost three family members in a 2018 drug-driving crash in Waverly said it was “unacceptable” that ministers were sitting on proposals for roadside testing “when more than 70 lives a year are lost to drugged drivers.”

But Porteous’ figures are complicated by the crucial inability of most drug testing methods to distinguish between the presence of drugs and actual impairment. As stated repeatedly in the media this week, 71 people were killed on our roads after using drugs. This is literally true, but as Professor Thomas Lumley, Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland told The Spinoff last year, the AA report where that number first appeared was only looking at the number of times that drugs appear in Police’s Crash Analysis System Reports.

“But for something to appear on there, the police only need to have decided that it’s possibly a contributing cause,” Lumley said. “If they test and find drugs, they’re going to be relatively unlikely to conclude that it didn’t contribute.”

“It makes a better headline, it could be true, but there’s not much support for it in that data, and there’s no straightforward way to say if those crashes were caused by drugs.”

NGOs and academics say there are similar problems with the accuracy of saliva testing, a testing method advocated by Simon Bridges, who declined for the three years as transport minister to instigate a regime.

Dr Fiona Hutton, senior lecturer at the school of social and cultural studies at Victoria University said it was encouraging the government were focused on impairment, but pointed to the detectable life of compounds like THC, saying she hoped any legislation would consider the length of time cannabinoids linger in the body.

“Roadside testing must not fall into the trap that workplace testing has, and make sure that drivers who are drug tested at the roadside are actually those who are impaired,” she said.

Nick Smith has said repeatedly National believes the technology is ready to make that distinction, pointing to Victoria in Australia which has instituted the tests. But Bell said they’ve proven to be expensive and inefficient, with concerning amounts of both false negatives and false positives. Thomas Lumley agreed, saying roadside point-and-shoot tests for impairment like an alcohol breathalyzer just don’t exist for some substances.

“For some of these drugs there just isn’t a good test for impairment that you can do biochemically,” said Lumley last year. “Heavy cannabis users may not be impaired despite it being in their body. The point of testing drivers is to find impaired drivers, not to find people who smoke cannabis.”

For now, experts say the best option is to stick with what we have, because the impairment testing described by Swarbrick isn’t as janky as it seems. Bell said the issue is not with accuracy, where studies have shown up to 95% confidence in results, but overall police confidence and competency – a tangible challenge, and a solvable one.

“The problem is we don’t train enough cops. The cops that are trained are great, they are extremely accurate, but sometimes they don’t do it often enough to feel confident. So you have this issue where the police themselves back saliva testing because they feel like the impairment test is too much of a potential hassle.

“They’d rather have technology, but wouldn’t we all?”