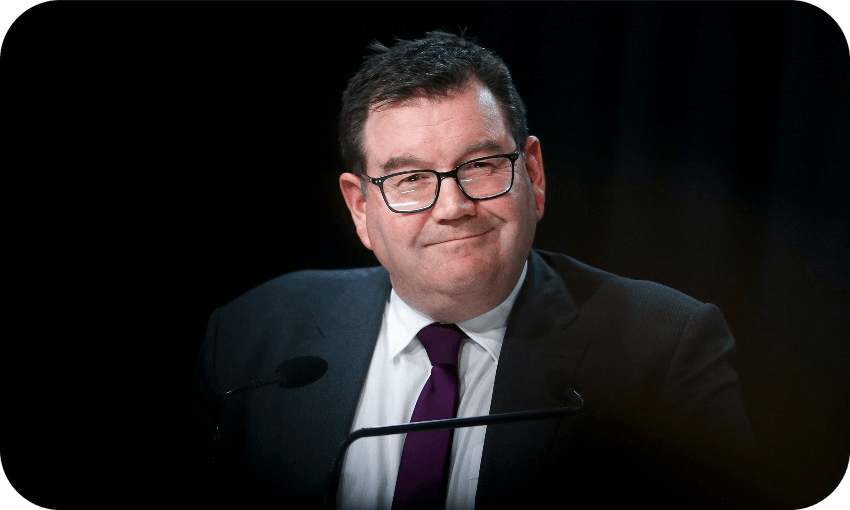

As he returns to Dunedin, parliament watchers will wave farewell to the most captivating debater of his political generation.

The list of politicians who could have been prime minister but said no thanks is a short one. When Jacinda Ardern determined in the dying weeks of 2022 that it would soon be time to go, the role of Labour leader and therefore PM was Grant Robertson’s if he wanted it. He’d previously said he didn’t want the job, but that would have been a simple hurdle to leap – the circumstances had changed, the moment called, and so on.

That he still didn’t want the job – a job he’d coveted for most of his life – was down to the same stuff that prompted Ardern to exit: a depletion of politician gas. He’d seen the role of prime minister up close across five years, and “I think you’ve got to be honest with yourself and honest with the public whether the desire is there to do that”, Robertson said at the time.

Given all that, and chuck into the mix Robertson’s decision not to stand for a sixth term as MP for Wellington Central (so obviating the need for a byelection should he slip out during the term), the only question around his departure from parliament was how soon. The timing, prompted in part by a wish to help the caucus settle into opposition and in part, we now know, by his appointment as the next vice chancellor at an embattled University of Otago, affords him a couple of months off before he heads back to his beloved Dunedin in July.

Robertson quickly made an impression as a strong parliamentary performer after he was elected as MP for Wellington Central in 2008. He’d had some practice, after all, having earlier worked on Question Time prep for Marian Hobbs, Wellington Central MP before him. He’d take on the persona of the questioner, usually Act’s Rodney Hide. “He would just fire questions at me, every possible question in the book, and I would go bang bang bang bang bang,” Hobbs told Madeleine Chapman in a 2021 profile. “He gave me back my confidence.”

Hobbs’ performance was so improved that Helen Clark’s office swooped in and poached the young adviser. There he played an integral role in designing the interest-free student loans policy credited with getting Labour over the line in 2005.

Robertson’s twin extra-curricular obsessions, New Zealand sport and New Zealand music, appeared as early as his maiden speech, in which he noted he’d met his partner, Alf, playing rugby, and quoted a Muttonbirds lyric.

He paid tribute to gay parliamentarians who had gone before him, adding: “Being gay is part of who I am, just as is being a former diplomat, a fan of the mighty Ranfurly Shield, the Wellington Lions, and a fan of New Zealand music and New Zealand literature. My political view is defined by my sexuality only inasmuch as it has given me an insight into how people can be marginalised and discriminated against, and how much I abhor that. I am lucky that I have largely grown up in a generation that is not fixated on issues such as sexual orientation. I am not – and neither should others be.”

Robertson twice stood for the Labour leadership. Nominated by Jacinda Ardern and Megan Woods in 2013, he was the most popular choice among fellow MPs, but finished second to David Cunliffe, who won the most support from members and unions. Across the campaign, which included hustings across the country, Robertson faced numerous media questions, many which felt anachronistic on delivery, about whether New Zealand was ready for a gay prime minister.

In 2014, Robertson came within a whisker of the leadership, losing to Andrew Little in the final count by a single percentage point. He was the most popular candidate among the Labour caucus and the party membership, but Little prevailed thanks to the overwhelming support of unions. That was that, said Robertson – he would not run for the leadership again.

He had stood then alongside would-be deputy Ardern – “Gracinda”, as the ticket came to be known. As his friend’s star continued to rise, it became clear that Labour’s formula for success would one day come with those roles reversed.

Speaking following today’s announcement on a “huge day of mixed emotions”, Robertson cited “the role I played in getting New Zealand economically through Covid” as the political achievement of which he was most proud. “We saved lives, but we also saved livelihoods,” he said. As the local MP and a senior minister, the toughest time was the parliamentary occupation of 2022, he said. “I found that incredibly hard personally.” To his critics, however, Robertson’s epitaph as finance minister is defined by a ballooning crown debt, and efforts to rein in spending that came long after the horse had bolted.

One of the most fascinating chapters in Robertson’s memoir, when it comes, will be on the 2023 decisions around Labour tax policy. He and David Parker had advocated for a “tax switch” that included a wealth tax, which was kiboshed by the party’s bread-and-butter leader. He was then forced to publicly insist he had come around to the idea of removing GST from fresh fruit and vegetables, a policy he had previously, forcefully decried as a mess, a “boondoggle”.

In reconciling his earlier stance with his stated new position ahead of the launch of that policy he deployed his superpower. The venue was a Hutt Valley church. “I want to thank St Paul’s for allowing us to use this venue today,” he said. “I don’t represent myself as any kind of saint but I’ve been on my own road to Damascus when it comes to the announcements we’re making today.”

But when he was quizzed afterwards, he delivered a straight bat and some of the most clenched teeth I’ve ever seen. He knew, of course, that there was no point in creating a Lange-Douglas style division. He knew the leader ultimately made the call. Just as he knew that he could have been that leader, and he turned it down.

Across six years as minister of finance, Robertson chewed through half a dozen opposition spokespeople, delighting in going head to head in parliamentary debate.

That changed with Nicola Willis. By then the hangover from a Covid spending binge had firmly setting in. And Luxon’s appointment as finance minister proved quickly that she had the chops. Just as Robertson had served his apprenticeship in Helen Clark’s prime ministerial office, Willis had learned her craft in John Key’s Beehive.

In the leadup to the election, when Robertson lashed out at Willis, accusing her of lying over claims of a fiscal hole in Labour’s costings around that fresh fruit GST policy, it seemed out of character. For whatever reason, his usual ability to casually rise above criticism or deflect with a verbal prod had abandoned him. He must by then have known that the government’s time was up, and so, soon enough, his time as an MP would be, too.

The most immediately visible hole that Robertson will leave is in the debating chamber, where he has proved himself consistently the most compelling speaker of his political generation. Whether making a principled argument, doing pure politics in general debate or a comedy special at adjournment, Robertson could reliably deliver a captivating, percussive, off-the-cuff speech.

He was one of the few for whom you’d routinely unmute Parliament TV. In a house where debate is so often milquetoast script reading and soporific talking points, Robertson at his best recalled the blast and wit of David Lange.

As excoriating as he could sometimes be in the house, Robertson is also known for a generosity of spirit. In her own tribute today, Ardern spoke of a “selfless, thoughtful, incredibly intelligent, fiercely loyal, and to top it off, one of the funniest people I know.”

Just as Lange’s oratory inspired a big, bespectacled kid in Dunedin in the 80s, Robertson is sure to have had his own impact, including on members of the rainbow community.

At 52, he’s still a spring chicken, and he certainly can’t be accused of signing off and taking it easy. In returning to the University of Otago – – as vice-chancellor he will lead an institution in a sticky financial predicament, in a bruised and battered tertiary sector.

If he needs to summon the energy he could look to the inspiration of Grant Robertson, the president of the students’ association who, in 1993, found himself one of 13 arrested (though not charged) after riot police rounded on a demonstration on the Union Lawn. His cause? Railing against a University Council and vice-chancellor plotting a 15% increase in course fees.