Over two years in Nauru, I met many of the 119 children who have been left languishing by Australia and Nauru on the island. At the Pacific Island Forum, Jacinda Ardern has an opportunity to take a stand, and to change these kids’ lives, writes James Harris of World Vision

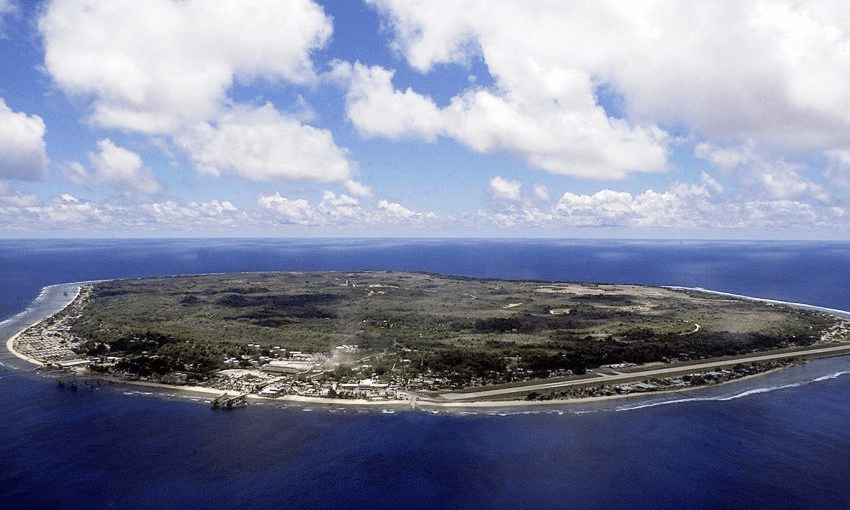

From 2012 to 2014 I spent two years on Nauru, a Pacific island nation about the size of Rangitoto, providing welfare services to asylum seekers detained there by the Australian government.

One day I was speaking with a 13-year-old Iranian girl trapped in the detention centre. Her family had fled for their lives due to government crackdowns on political opposition. She asked me where I was from, and when I said New Zealand, she told me the Kiwi security guards were her favourite and that she was learning Te Reo Māori from them. With the detention centre fences towering over us she looked me in the eye and said to me with a hopeful smile, “Kia kaha”. It is a moment of resilience and beauty I will never forget.

One hundred and nineteen children are still on Nauru, languishing in limbo. During my time there I saw children crumble under the weight of indefinite detention.

Together with their families, they have fled persecution, war, violence and, for some, certain death. They left their homes, eventually boarding boats, hoping for a safer life in Australia.

But in July 2013, the Australian government announced that anyone who arrived by boat, seeking protection on their shores, would never live in Australia. Instead, they would be detained in Nauru and Papua New Guinea until they were settled elsewhere.

I was in Nauru when the first children and their families arrived. Five years later, many of them still remain. None of them can return home, even if they wanted to. Robbed of their childhoods and futures, the detaining of children on Nauru amounts to nothing less than child abuse at the hands of the Australian and Nauruan governments.

Kiwis were outraged when they heard about asylum seekers’ children being detained in the United States. We stood up and protested: locking up children is never the answer.

As the New Zealand government prepares to attend the Pacific Islands Forum in Nauru in early September, now is the time to address the fact that it is happening in our own backyard. World Vision is calling on Jacinda Ardern to use this meeting to negotiate the immediate resettlement of all 119 children and their families currently detained on Nauru as part of an emergency intake over and above our refugee quota.

Despite their harrowing circumstances, some of the kindest, most hospitable people I have ever met are being held on Nauru. Although they have nothing, they would still find ways to exhibit the generosity that underpins their characters and cultures. Any country would be lucky to have them. However they are trapped in a brutal system that not only doesn’t acknowledge their generosity, warm natures or hospitality; it denies their humanity altogether.

These people are essentially trapped, living in conditions no human, let alone child, should have to endure. Their movement is restricted, they lack access to adequate healthcare and education, and due to the absence of accommodation on the tiny island, are subject to living in cramped and overpopulated houses, if not tents.

What these children and their families are subjected to mentally has a far greater toll. When they arrive on Nauru, they are assigned “Boat Ids” – three letters and three numbers. Staff would often call them by their “ID”. People with names like Michael, Ravi and Miriam. It didn’t take long before the Michaels, Ravis and Miriams began to identify as their numbers. I’d often ask a person what his or her name was, and they’d tell me their Boat ID, as if that was who they were. They had become no longer a human being with innate worth, just a number.

It’s not surprising that suicide attempts and self harm are frequent occurrences among the refugees on Nauru.

The New Zealand government has a chance to end this at the Pacific Islands Forum. I take heart that New Zealand has already offered to resettle the children and their families trapped there – not once, but twice. But Australia have declined.

We should not accept Australia’s insistence that we wait until their resettlement deal with the United States is complete. That process is moving too slowly, and since President Trump’s travel ban, we know most of these 119 children and their families – people from Iran, Syria, Somalia and other nations now banned from entering America – have no hope to be included in the resettlement agreement between Australia and the US.

The prime minister must use the Forum to negotiate directly with the government of Nauru, or else these kids will remain in limbo, subject to abuse, mental distress and major risks to their health, unless New Zealand steps in.

As the Pacific Island Forum draws closer, I am reminded of the historic political moment 17 years ago, when then prime minister Helen Clark relentlessly negotiated to rescue the Tampa refugees from the island of Nauru and bring them to Aotearoa to restart their lives. To this day, Clark refers to this as the act she is most proud of in her long political career.

Just as the 13-year-old Iranian girl said to me, this is now my message to Jacinda Ardern, the leader of our generous and hospitable nation: Kia kaha – be strong and brave – and in the face of injustice in our backyard, let’s take a stand and get the kids off Nauru.

James Harris is community engagement manager at World Vision NZ, which today launches its #KidsOffNauru campaign.

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.