The government made big promises about being open with the public. But did it live up to them? Max Rashbrooke asked journalists – and consulted the evidence.

Some words and phrases weigh heavily on this government, like a concrete-block necklace. “Kiwibuild” is one such. Another is the promise made in November 2017 by MP Clare Curran, just a month after Labour had taken power, that hers would be “the most open and transparent” administration this country had ever seen.

Curran was soon after forced to resign from her role as minister for open government, but the ambition remained, at least notionally. And her words only reformulated, in striking language, sentiments uttered by her then prime minister, Jacinda Ardern. But open and transparent government has often eluded Labour, as it has faced all the usual temptations to limit the public’s role in decision-making and conceal information. So how well has it fulfilled Curran’s promise?

One respected voice on these matters is Keitha Booth, who from 2008 to 2015 led New Zealand’s Open Government Information and Data Programme. “There has been progress,” she says of Labour’s efforts. Openness is partly about creating more opportunities for people to be involved in politics: Booth points to recent experiments with citizens’ assemblies, albeit largely at the local level, and – more contentiously for some – co-governance. Such innovations “seem to be becoming embedded”. However, she bemoans the lack of “public leadership on open government at the ministerial level”, noting that the responsible ministers, among them Chris Hipkins and Andrew Little, have generally been “far too busy” with other portfolios.

Opacity and privilege have also generated the usual parade of scandals, from the Ministry of Health removing unwelcome statistics from its reports to Stuart Nash disclosing confidential Cabinet information to donors. The government, however, bases its defence of Curran’s pledge on three pillars: the promised creation of a register of the true (“beneficial”) owners of New Zealand companies, the formalised publication of Cabinet papers (something that happened piecemeal under previous governments), and the release of ministers’ engagement diaries. All are potentially important reforms. But none has been perfectly delivered.

The beneficial ownership register could, experts believe, represent real change, making it easier to determine who owns firms currently veiled in layers of shell companies and trusts, and to track down those responsible for corporate wrong-doing. But it is still a work in progress, and in any case represents openness from companies, not the government itself.

Meanwhile, on some measures, under half of all Cabinet papers are actually released. Promises of proactive publication are also, ironically, being used to refuse information requests, journalists say. As one puts it: “Too many papers are not released [at the time they would normally be], because the government promises to ‘proactively’ release them at some undetermined time in the future … when it is no longer of use to the media or the public.” (In passing, it should be noted that many countries are amazed we publish Cabinet papers at all.) The ministerial diaries, meanwhile, can be difficult to find online, are formatted as hard-to-use PDFs, and may not contain all the meetings of interest.

One festering sore is the continued failure to overhaul the 1982 Official Information Act (OIA), which plays a vital role in mandating the release of public data and documents but is widely seen as needing renewal. In 2020, Little promised a full review, but it was “deferred” by his successor, Kris Faafoi, and never eventuated. In its absence, reporters have complained that abuse of the act has accelerated, just as it did under John Key and, before him, Helen Clark. Official statistics show more requests for information are being answered within deadlines, but that says little about the quality of the responses’ compliance with the law.

Journalists report releases being heavily redacted, given to other, “friendlier” reporters, or simply withheld without good reason. Anna Fifield, when editor of the Dominion Post, castigated the government for its “obstructive and deliberately untransparent” culture – one that was worse even than in the other democracies she had covered.

To test how widely this view is shared, The Spinoff contacted half a dozen members of the Press Gallery, all of them journalists who have followed multiple administrations closely, asking them for impressions of this government’s performance and a ranking from 1 (much more open and transparent than its predecessors) to 5 (much less).

Their combined responses could be summarised in one word: meh. One experienced journalist said Labour had been “slightly more open and transparent, because my impression – and that’s all it is – is that the proactive release of officials’ and Cabinet papers has become an important source to allow deeper analysis of how decisions have been reached.” But they noted “significant ways in which the government as a whole has become less transparent”, especially now that departments’ press teams virtually bar reporters from speaking directly to officials.

This practice was, another journalist added, “particularly problematic in a tiny country in New Zealand, where some of the best experts and voices on any subject are employed by the public sector”. But on the wider question, this journalist thought that the government “win[s] on a technicality. They are more open and transparent than other governments, but only because previous governments have been particularly opaque.”

Some agencies were praised for proactively releasing material, notably the Treasury and ACC. There was a widespread sense that, among ministers, Hipkins had been one of the best, but had often failed to bring colleagues with him. “It’s a real mixed bag,” one journalist said of the overall record. “The intent has been good in many respects, but it’s the execution that has been the issue.”

Others were even less enthusiastic. “I have noticed no obvious change in [official information] responses since the change of government,” one journalist wrote. “Still reliably up to the line on timing, sometimes over; still redactions and omissions which seem to me dubious. I have noticed an uptick in responses to straightforward inquiries that comms people chuck in the [much slower] OIA pipe, which is incredibly frustrating.”

One journalist, even more scathing, said the failure to review the 40-year old OIA was “the clearest signal you need that [Labour] was never committed to open government”. They added: “A culture of secrecy and obfuscation has bled down from the Beehive into the public service … As a working journalist, I have found it increasingly difficult to get straight answers to questions. It also takes twice, three times as long because every paragraph is parsed until it is reduced to a statement that tells you absolutely nothing.”

So how did the reporters rank Labour’s performance, overall? Their scores averaged out as a ‘3’ – suggesting there was nothing, on balance, to differentiate this government from any other.

This tepid response is supported by global comparisons such as the Open Budget Survey, which examines how readily the public can find information on the government’s finances. It does not make encouraging reading. From a high of 89 (out of 100) in 2017, New Zealand’s score fell to 87 in 2019 and then 85 in 2021. Partly this reflects the high-speed, pandemic-driven rewriting of the 2020 Budget; many countries experienced similar falls. Still: hardly a resounding endorsement of Curran’s ambition.

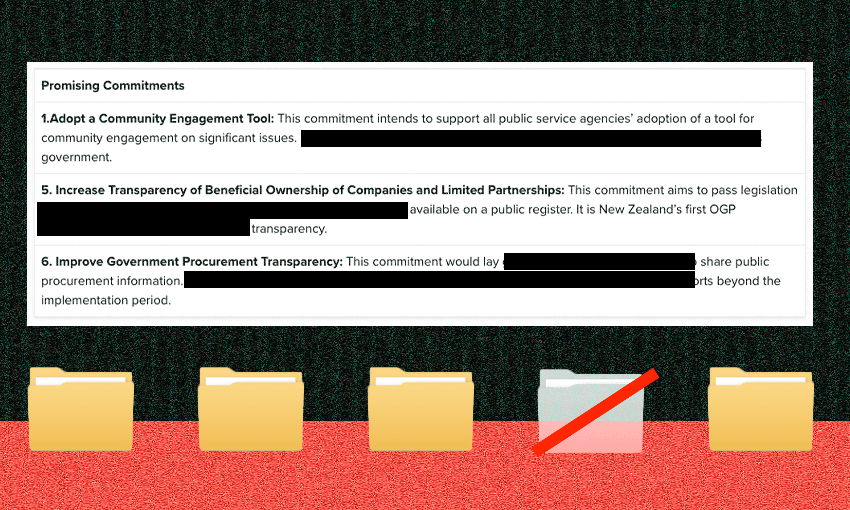

On the plus side, Labour has paid more attention than National to the Open Government Partnership, an initiative in which 76 countries draw up regular action plans to improve participation and transparency. New Zealand’s first such plan, developed under National in 2014, was a derisory list of things that were already happening. Under Labour, the plans have – from this low bar – become more substantial.

But they are still hardly ground-breaking. The independent audit of Labour’s latest plan suggests just three of its eight measures are “promising”, and even that assessment seems generous. One measure involves nothing more than “lay[ing] groundwork for online platforms to share public procurement information”.

Worst of all, NGOs say, there is nothing in the plan to stop the introduction of the “secrecy” clauses increasingly being written into legislation to override the OIA. Labour alone has brought in over 30 – “a significant stain against its claims on open government”, says Andrew Ecclestone of the New Zealand Council of Civil Liberties, the NGO most active in this field. The proposal is instead to strengthen the scrutiny of more such clauses in future: the “open government” action plan, in other words, actively envisages greater secrecy.

So there it is. The government may claim that its three big changes – the promised beneficial ownership register, the regular release of Cabinet papers and the publication of ministerial diaries – are by themselves enough to lift it into “most open and transparent” territory. But the failings noted above, alongside the slight declines in global rankings, the usual parade of scandals and the ambivalent rankings of experienced journalists, argue the other way. And even some of those who deem the pledge technically fulfilled would concede that Curran’s language invoked a whole-of-government step-change: a transformative improvement, to use the adjective favoured by early-stage Ardern. And of that there is no evidence at all.