As it adjusts to life in opposition, National needs to focus on defending capitalism against a coalition of socialists and populists, writes former National ministerial adviser Zach Castles.

It’s less than a week ago that Winston Peters appointed a Labour government. I’m still gutted.

And while I don’t need a lecture on the dangers of comparing First Past the Post and MMP, National’s share of the vote was larger than Theresa May’s in June, or Malcolm Turnbull’s last year. It was a Labour Party activist who reminded me on election night to consider how impressive it was for a government seeking a fourth term to achieve the result it did.

I’m punching away at my keyboard in a café overlooking the Thames as I pore over the news at New Zealand’s government for the next three years, but I’m still reflecting on where the last nine went.

Aside from Angela Merkel’s government in Germany, many of the governments – and in some cases prime ministers – that were so quickly swept to power following the Global Financial Crisis have been just as quickly swept out of office. And in the case of New Zealand, National has been ousted despite comfortably winning more votes than any other party.

National wasn’t totally ready for Jacinda Ardern – but by her own admission, she wasn’t really ready either. Nevertheless, the challenges now head in Labour’s direction rather than National’s for the first time in nearly a decade, and what matters most of all is how National rises to the occasion.

Some perspective is needed here. Labour has demonstrated that with the right leader and right machinations it no longer needs to win elections to take power. And what exactly those forces behind our new prime minister plan to do with that power should not be underestimated.

The incoming government makes no secret of its regard for capitalism as a “blatant” failure. This is despite nearly one billion people over the last 20 years having been lifted out of poverty because of it. Moreover, the very “neoliberalism” the incoming prime minister criticises, and yet refuses to define, has helped many Kiwis out of a life of welfare dependence and into the dignity of a job.

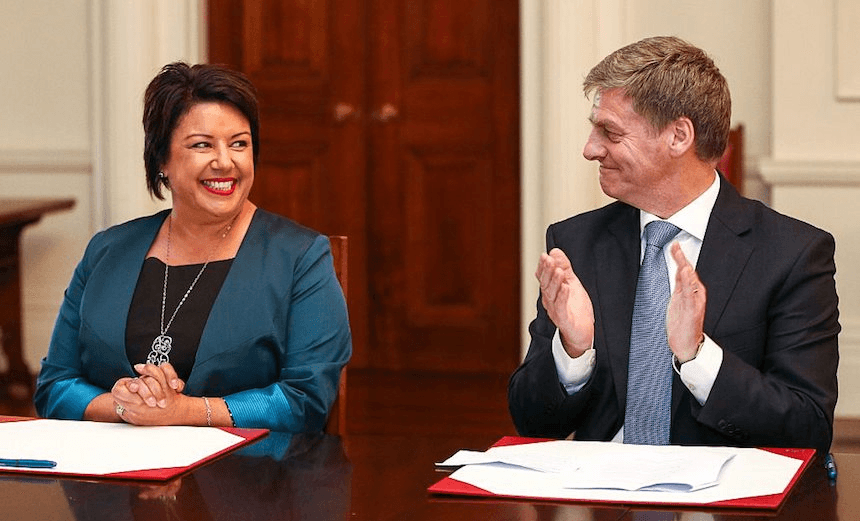

No one is saying capitalism is perfect. Especially Bill English. His entire social investment approach, one I had the privilege of working on government, anticipates this by accepting that governments must invest more money early on to reduce the cost of crime, health inequalities and intergenerational welfare dependence.

But to engage with Jacinda Ardern’s attempt at class warfare rather than to call it out is to New Zealand’s detriment.

Indeed, to not do so would in fact undermine the very routes out of poverty – like an innovative economy, a competitive labour market, and open borders that invite the wealth of talent that make New Zealand the diverse and ambitious country that it is.

The return of the left to government now means everything that makes New Zealand such a role model, at a time of supposed global despair, now hangs in the balance. We were meant to be the poster child for globalism, free trade and ambition; now we are being set up as the test flight for a return to the 1970s. A world Jacinda Ardern’s own voters have never actually known.

National’s political foundations are Burkean by instinct – an instinct shaped by evolution, not revolution. And throughout its 80-year history, very rarely has National been a party of change.

However, in recent decades, from the radicalism of Ruth Richardson to the ‘radical incrementalism’ of Bill English, National has successfully established itself as a modern and liberal party that embraces – rather than simply tolerates – its role in leading transformative social and economic change. Take for example the fundamental reforms to child protection and the welfare reforms advanced by Anne Tolley and Paula Bennett, or National’s legacy honouring property rights by rapidly settling treaty claims. Or even the visionary but ultimately futile attempt by Amy Adams to reform the RMA to make New Zealanders freer to build their own homes.

In a world of Brexit and Trump, and a media-branded upsurge against perceived “neoliberalism”, the question is no longer whether National is capable of reform, but how far it is prepared to redefine a centre ground that is rapidly shifting in the direction of Jeremy Corbyn, the far-left leader of the UK Labour Party. The fact that National and New Zealand First are not in government shows that this process is already underway. A fundamental schism between the socialist left’s unholy union with authoritarian populism on one side, and the liberal right on the other, is opening up.

Far from being in a “very, very dark place” as Paddy Gower was quick to assert, National has just been handed a golden opportunity. In fact, the biggest impact Bill English can make now on the National Party, more than at any other time in his political career, will be in these initial weeks and months.

As the party regroups and refocuses its efforts, National has never had a better opportunity to make capitalism cool again by re-making the case that it is the best tool we have to transform lives in a dangerous and uncertain world. Indeed, transforming lives through the investment approach is the essence of the Key-English legacy, and it is National’s task to defend that legacy and advance its cause vigorously in the next three years.