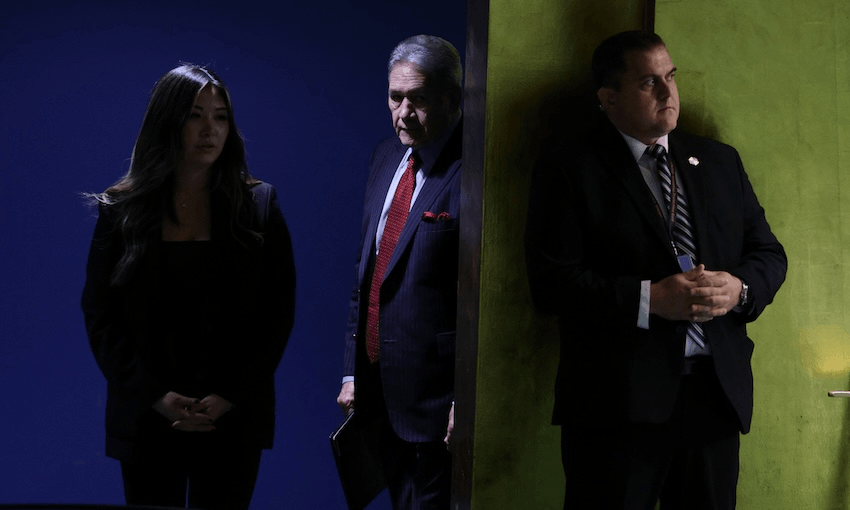

At a time when, as Winston Peters said, the international system ‘stands on the precipice of breaking down’, New Zealand’s position may chip away at what remains of its foundation, writes international law scholar Ash Stanley-Ryan.

At the UN General Assembly on Saturday, New Zealand opted not only not to recognise the state of Palestine, but denied that it met the criteria to be considered a state. It premised this view on the Montevideo Convention’s criteria – which can be summarised as a permanent population, a defined territory and an effective government – and in effect suggested that recognition today would be merely symbolic.

It is important to say two things about Montevideo. Firstly, the Montevideo criteria are unevenly and inconsistently applied by states. Secondly, if the New Zealand government considers that these criteria are the definitive and sole determinators of statehood, and if that is a correct understanding of the law, New Zealanders should not expect any change in the state’s position until the day after the occupation of Palestine is brought to a close. This is because a state which is born out of occupation, which remains in its entirety occupied and which has its existence denied by the occupying power, can hardly be expected to have either a clearly defined territory or an effective government.

New Zealand has taken a clear position, but it has done so on the basis of a deeply prescriptive and debatable understanding of the law of statehood. It has exercised its independent foreign policy, but in a manner which fails to signal a coherent vision of what international law demands of us. In short, the decision is difficult to justify as a matter of law or policy.

But this is not a piece about the justifiability of New Zealand’s decision. This piece is about what could have been, and what remains.

What could have been

There are things recognition would do, and things it would not. In this very limited sense, recognition of Palestine is “an existential act of defiance against an unalterable state of affairs”. It would not improve the situation on the ground in Israel or in Palestine. It would not restore our common humanity which, in the Gaza Strip, has died 60,000 deaths. It would not end the prolonged occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem. It would not free the state of Palestine; the soul of a nation, long suppressed, will not find utterance until the unlawful occupation – of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, which together form an indivisible whole – ends. Nor would recognition bring back the 1,200 Israelis whose lives were stolen on October 7, or secure the return of those who remain the hostages of an organisation that has no regard for human life and dignity.

But the political decision to recognise Palestine, even conditionally, would have had legal effect. It would have definitively triggered the complex bundle of obligations states owe to each other. These include the principle of sovereign equality and the absolute prohibition of aggression and the non-defensive use of force. Once a state is recognised, it cannot be argued that these rules do not apply. This matters: had New Zealand recognised Palestine it would have a duty to do what it can to ensure respect for many rules of international law, and an obligation never to recognise situations arising from violations of the most fundamental rules as lawful.

Recognition would also have made it difficult to see how New Zealand could do anything other than work for the full and effective implementation of the 2024 advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice; it already must do so, but that obligation would carry even more weight when combined with the obligations owed between states. Recognition would therefore not only have concretised some positions that New Zealand already holds as a matter of policy; it could also have required New Zealand to go further than it has to date, in order to guarantee respect for international law.

It also would have signalled, concretely, real and genuine support for the Palestinian people’s peremptory right of self-determination, from which no derogation is permitted. This signalling function is important for Israel and Palestine alike. To Israel it signals that here lies the boundary; a future without an independent state of Palestine, within the pre-1967 borders, is unlawful. To Palestine, it signals that support for statehood and self-determination is something more than mere words. To both, it signals that the existence of the other is non-negotiable. It was a chance to join the chorus of the vast majority of the international community in saying that the only safe future is one of two states, existing side-by-side, at peace. And in fairness, New Zealand did join that chorus: it reaffirmed the necessity of the two-state solution. But it sang in a different key.

Recognition would additionally have served a world-shaping role: when we accept an actor as a state, we accept its permanence. A state’s sovereign equality means it is protected; its factual existence cannot be taken away from it, even by oppression and recognition cannot be withdrawn by caprice or whim. That logic – sovereignty and continuity – underlies the concept of states in international law. Recognising Palestine would have affirmed that it is legally impossible for another state to extinguish the flame of its personality. The position taken achieves the opposite: at a time when, as foreign minister Winston Peters said, the international system “stands on the precipice of breaking down”, New Zealand’s position may chip away at what remains of its foundation, because it has placed itself in direct opposition to most of the international community on a fundamental question.

What remains

New Zealand’s position does not change that it has legal obligations regarding Israel, Palestine and the ongoing armed conflict and occupation. New Zealand remains obliged to take all the measures at its disposal to ensure respect for international humanitarian law – by Israel and by Hamas – and to do everything it can to prevent acts that risk violating our most basic internationally agreed rules. It remains under an obligation not to support or recognise as lawful the occupation, or any situation flowing from it. It continues to carry obligations as a member of the International Criminal Court. And it remains true that, as the International Court of Justice has said, the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination is so fundamental that it is peremptory. These things remain.

The views expressed in this piece are the author’s alone and are expressed in their personal capacity.