Lucy Zee looks back on the late-nineties, early-aughts infomercial craze that was… Nad’s.

In my prepubescent tweens, I started to notice body hair on myself. My arms, my legs, my armpits, my upper lip. I wasn’t so much upset but more curious than anything. Why did we grow hair in these places? When does it stop? Who did my mum buy this Venus razor for?

Body hair was on the mind and apparently on the TV too. In the early 2000s, at 10am on a weekday, you were hard pressed to find a channel showing anything other than blenders, mops and magnet wool mattress toppers but there was one infomercial that stuck out. Through all the American male voiceovers there was a different type of infomercial – a beautiful pale skinned, dark haired woman stood in front of the camera and in an Australian accent she said:

“As a mother, it broke my heart to see my daughter upset because of her unwanted body hair, so I created Nads, a natural hair removal product….”

Insert *disc_scratch_epic_audio_fx_limewire_sd8mokey.mp3* sound effect.

My hairy 13 year old ears were listening.

Nads was touted as a kitchen creation born from the love of a mother for her hairy daughter. Sue Ismeil, the creator of the Australian-based international brand created the hair removal gel by tweaking her grandmother’s original recipe. Sue created the molasses and lemon concoction in her own home, using it on her daughter, her friends and co-workers and eventually becoming an international multi-million dollar company.

The infomercial spoke about her family, examples of hair removal on real-life hairy humans and a heavy emphasis on how natural it was. It spawned so many more baby infomercials that over the next few years Nad’s was impossible to miss on TV.

Here are some iconic moments from a truly strange moment in the golden years of Nad’s infomercial fame:

Real life hair removal on screen

I had never seen anyone get waxed before. Even in movies it seemed fake, over acting and stigmatised with pain – kinda like seeing a childbirth scene. Honestly, is it really that bad?

The Nad’s infomercial had Sue using the product on real life people, very precisely smearing on the product and quickly ripping off the cloth. Perhaps to this day it’s one of the smoothest waxing methods I have ever seen in my life and trust, I have seen many a waxing method in my life.

Whether the actors in the infomercials were paid extra to not cry, or it was genuinely painless, it inspired me as a young adult to keep as still as possible while getting a wax. To this day you will never see me flinch nor let water leak from my eye while getting waxed.

Catchy slogans

They really tried to revolutionise the hair removal business by trying to not use the words ‘wax’, ‘depilate’, ‘pluck’, ‘strip hairs’, and ‘smearing sugar over your body and ripping each strand from the root’. So they went with what they thought was natural for their brand: “I got Nadded!”

Me: Excuse me police officer!

Police: What seems to be the problem ma’am?

Me: *holds out bare arms* I just got Nadded.

Police: You’re under arrest for trying to create a new adjective!

Me: noooOOoooOoo lol

Keeping it in the family

Sue created this product for her daughters, so who better to help her sell it than her now bald-armed offspring. The majority of the rave reviews are from her raven-haired girls, who with huge smiles and playful giggles claim that it’s the best product since… ever? And they’ve used since they could… remember?

In one infomercial one of Sue’s daughters is playing part of a crispy tanned fantasy couple, both lying on the hot summer beach with their rock hard abs and hairless torsos. The shoots include lots of skin-on-skin stroking, seemingly in the hopes of moving the brand from “homely” to “sexy”.

Fun fact: Nad’s was named after Sue’s daughter (presumably the most hairy one), which is one of the most maternal things you could ever do as a mother. A family that Nad’s together, stays together, unless flushed with warm water and wiped carefully to dissolve any sticky residue.

Delicious

One of the marketing angles for the product was that it was made with natural ingredients. In a segment they even threatened to eat the product right in front of our eyes. I didn’t believe it – but there they went! Dipping their finger in it and putting it in their mouths. Going by their website and new commercials, it looks like they don’t encourage you to try eat it anymore, maybe they got sued after too many customers tried to eat the Nad’s AFTER they used it.

Surprise!

One of the many iterations of the infomercial featured a couple of American women talking about rummaging through their friend’s grubby bathroom cabinet – as you do – and screaming “YOU HAVE NAD’S???” I’m always rummaging through my friends bathrooms and screaming over my shoulder “YOU HAVE HANNIGANS HEMORRHOID CREAM??”

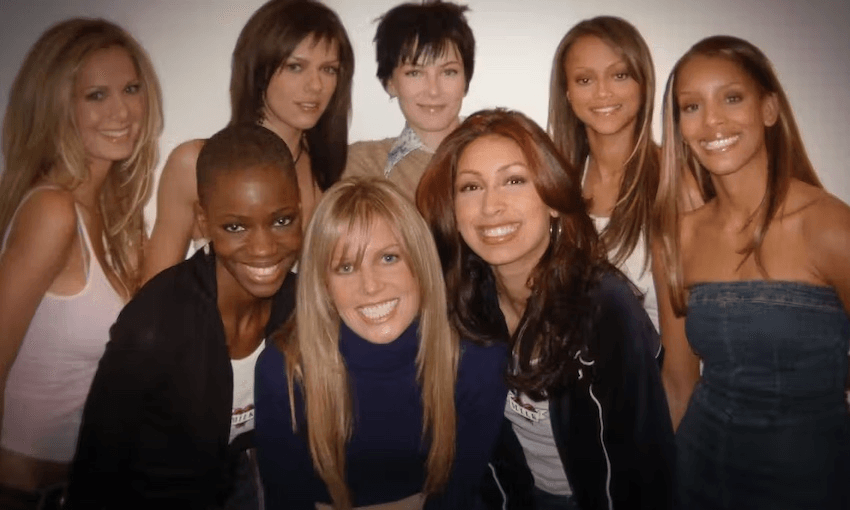

Then, in an incredible twist, Sue turns up to surprise the two women! Omg it’s the creator of this wax that I’ve used a couple of times!! Ekkkk, sign my hairless chest! This was the infomercial that really sold Nad’s to the difficult to crack US market. Turns out early 2000s Americans hated body hair on women as much as Australians and New Zealanders did!

Unwanted facial hair

If the evidence of real-life unedited video footage of women Nadding wasn’t enough to prove that it works, they also decided to turn heads of all the yet-to-be-woke early Y2K generation and bring out a woman who lived with excessive facial hair.

Sue and an American host sit at a table with another woman. She has something to show the host: she opens the front of her jacket pocket for some reason and pulls out a picture.

Crash zoom on the American host: “That is incredible!”

Mary Ann Roth lived with long facial hair around her chin and lip. She had accepted this was her life and didn’t see the point in dealing with constant removal and upkeep just to keep everyone else in her life happy. One day, Mary Ann’s mother gave her a jar of Nad’s and a magazine article about Sue – Mary Ann faxed Sue and the creator of Nad’s invited her straight over for a Nadding session.

She Nadded Mary Ann’s face for us right on camera, wowing us with a before and after. Mary Ann’s subtle delivery of her comments are the best part of this infomercial. With a very practised, fake smile she says “My mother… was so ecstatic and happy… Yes it was worth it to see my mother’s face.” Ahh the things we do just to make our mothers happy.

Since the launch of Nad’s, Sue Ismeil has created a $42 million dollar beauty empire, winning multiple Women in Business awards, funding over half a million dollars for research into the connection between hormones and depression in women, and donating thousands to charitable causes. She also personally donated $10,000 to a family whose daughter suffered from a large birthmark and excessive hair covering 40% of her face. Not bad for a little jar of sticky green syrup.

The Nad’s infomercial was my first introduction to hair removal. These days I wax and thread monthly but recently have been inspired to grow out my armpit hair. I’ve tried everything on the market but something inside me stops me ever reaching for the Nad’s on the supermarket shelf. The suspicious Sally in me was always taught to never trust anything in an informercial – I know that glitter star-wipe from the before and after images are just optical distractions. Those steak knives? They will go blunt. That ladder, it won’t transform and that hair removal product? That can’t be eaten.