Phasing out fossil fuels is the subject of much negotiation at Cop28 this week. But the wording will be fiercely debated, and the presence of fossil fuel lobbyists looms large.

This is an excerpt from our weekly environmental newsletter Future Proof, brought to you by AMP. Sign up here.

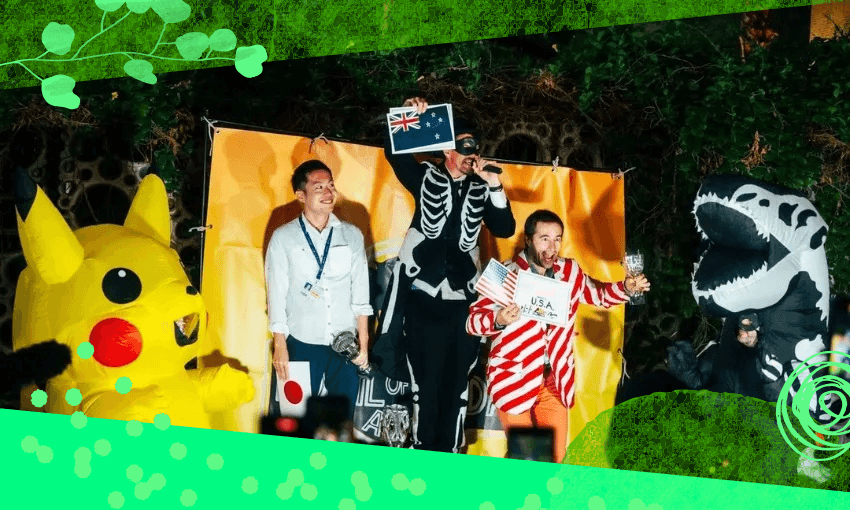

The government’s plans to reverse the ban on offshore oil and gas exploration earned New Zealand the first Fossil of the Day title at Cop28 in Dubai earlier this week. Climate Action Network International, who confer the dubious honour every day during the global climate summit, wrote, “Did New Zealand not read the road signs to Cop28??? No U-turns on the way to a healthy planet.”

The award comes as our Pacific neighbours, Palau and Vanuatu, criticised the plans to restart fossil fuel exploration. Chief executive of WWF-NZ, Kayla Kingdon-Bebb, told Newsroom that “all three parties, but National particularly, have seriously underestimated the kind of international backlash they’re going to see.”

In response, climate change minister Simon Watts pointed out that the previous government had also received Fossil of the Day dishonours at previous summits.

Closing time for fossil fuel production

The science is clear: if we are to limit global heating to 1.5°C, there can be no new oil, gas or coal projects. Ninety percent of the world’s coal and 60% of oil and gas need to remain underground. Oxfam Aotearoa has released a report outlining the how and why of a just transition away from fossil fuel production here in New Zealand, matching a “managed decline” of fossil fuel production with the creation of “good jobs in renewable energy, clean industries and social services”.

“Right now in Aotearoa, our oil and gas production is already declining at the rate we need to do an average share of the global phaseout needed for 1.5 degrees,” says report author Nick Henry. “To do our fair share we need to move faster, closing existing fields early.” The report points to Spain as a source of inspiration, where a “fast and fair” transition has seen the end of coal mining, and investment in green energy to support communities make the switch to a new industry.

Phase-out of fossil fuels on the cards at Cop28

A formal call for a phase-out of fossil fuels appears in one version of the draft negotiating text, Reuters reports. But the wording will be fiercely debated, and the presence of fossil fuel lobbyists looms large. There are 2,456 fossil fuel reps at the summit, according to Heated, seven times larger than the number of official Indigenous delegates.

Beyond the phase-out wording contest, there are a bunch of other issues to watch out for at Cop28. The first day of the summit saw a deal reached for a Loss and Damage Fund – which the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network says is significant, but doesn’t go far enough. New Zealand signed up to a declaration that agriculture and food production must urgently adapt to respond to climate change, but was absent from a list of more than 100 countries pledging to triple renewable energy by 2030. Laura Gemmell, writing on The Spinoff, has outlined five more areas to keep an eye on as the talkfest continues for another week.