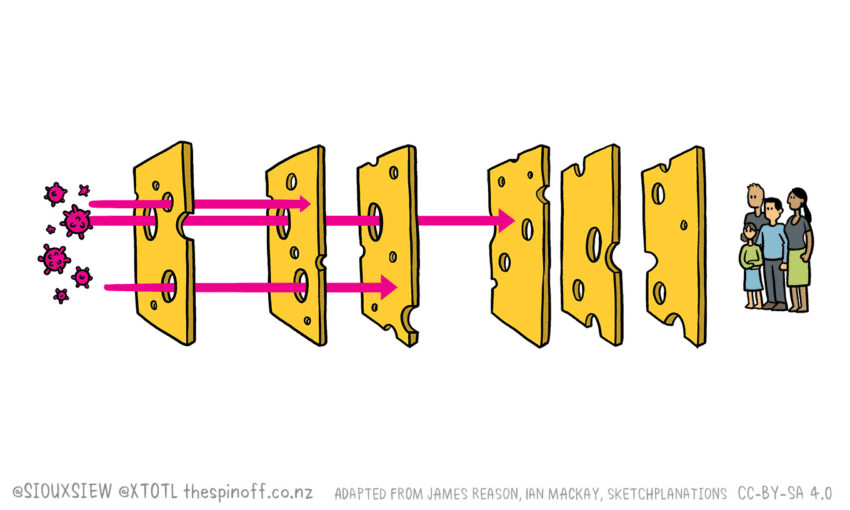

The effort to defeat the coronavirus relies on many layers of defence. Or, let’s call them, slices of cheese.

One thing that has really irked me during Covid-19 has been the labelling of any mistake in our systems or any unexpected transmission of the virus as a failure. Yes, I understand that the media and the opposition have a responsibility to hold the government and our public services to account, but screaming FAILURE from the rooftops has everyone looking for someone to blame and massively undermines public trust in New Zealand’s pandemic response. It’s also completely out of all proportion. If you want to see failure, look to countries like the US or the UK. Identifying mistakes or holes in our response is really important as it allows us to learn and adapt our processes, something that has been key to New Zealand’s success in managing Covid-19 so far.

Twenty years ago, James Reason, a professor of psychology at the University of Manchester in the UK, published a paper in the British Medical Journal in which he described what he called the “Swiss cheese model of system accidents”. Reason was trying to move people’s thinking from treating mistakes as individual errors by “bad” people to a systems approach that accepts that humans are fallible and mistakes are to be expected. Rather than blaming individuals for failure, we should try to understand how and why the failure happened to prevent it from happening again.

But what has Swiss cheese got to do with all this?

The idea behind the systems approach is to build in layers of barriers and safeguards. In an ideal world, each of these defensive layers would be impenetrable. But in the real world, they aren’t. So Reason likened each layer to a slice of Swiss cheese – it has holes in it. To be fair to the Swiss, they have lots of different cheeses, many of which don’t have holes, so it’s probably more accurate to call Reason’s model the “Emmental Model”.

Back to the holes. They can happen for many reasons. Slips, fumbles, mistakes. People not following procedure. Or they can even be built into the system. A hole in one layer of defence isn’t necessarily a disaster if there are lots of other layers to fall back on. Then its only when all the holes line up that the defences are breached. Reason’s model is now used all over the place including in medicine, engineering, and the aviation industry.

Applying the Swiss Cheese/Emmental Model to Covid-19

I’ve seen several excellent applications of the Swiss Cheese/Emmental Model to Covid-19, like this one by virologist Ian Mackay or this one by sketchplanations. They represent each of the different public health interventions we have for Covid-19 as layers of cheese. I love how they show that we actually have quite a few defences against Covid-19 but that none of them is impenetrable.

We have the use of border controls and putting travellers into isolation/quarantine to stop the importation of cases into a country or between regions. We also have the crucial package of rapid testing, contact tracing, and isolation of infectious people and their close contacts. This test-trace-isolate strategy can be used very effectively to stop the spread of the virus. Then there’s limitations on gathering sizes or the movement of people, or on high-risk activities or places.

We also have all the things we can do as individuals. Things like physical distancing, washing our hands, practising safe cough and sneeze hygiene, wearing a mask, using contact tracing apps to keep a track of where we’ve been and who with, staying home when sick, and getting tested if we have symptoms. And, finally, there’s cleaning and ventilation. Hopefully we’ll be adding vaccination next year.

New Zealand’s swiss cheese/Emmental model for managing Covid-19

Around the world, countries are applying different layers of cheese depending on the strategy they are following to deal with the pandemic. Herd immunity? What cheese? Flatten the curve? Some slices. Elimination? All the cheese!

Here in New Zealand, at the beginning of the pandemic we applied border controls as our first slice of cheese, along with physical distancing, handwashing, and cleaning. It was soon clear these weren’t going to be enough and the virus was way ahead of us. That’s when the alert levels were brought in, a framework of escalating restrictions on movement and activities.

A good way of thinking about the different alert levels is as slices of cheese with fewer and fewer holes as you move from level one to level four. We soon applied the slice with the fewest holes, backed up by managed isolation and quarantine of travellers as well as physical distancing, handwashing, and cleaning. That minimised importation of the virus into the country, and massively restricted community transmission of the virus. It also bought us time to ramp up the country’s testing and contact tracing capabilities, including the development of an app.

Applying all those slices of cheese got us to elimination. But then one by one we started stripping back the layers as we became more and more complacent. Until all that was really left were the border controls and managed isolation and quarantine. Those slices have worked fantastically well, but we know they aren’t impenetrable.

Fast forward to August, when someone in the community with no links to the border tested positive for Covid-19. Quickly many of the slices of cheese we’d used before were applied, as well as a new one, masks. And they worked, again. We’re back to no cases of Covid-19 in the community. It’s looking like we’ve eliminated the virus again.

Elimination is something we have to keep working at

As long as people continue arriving in New Zealand from countries with widespread community transmission of Covid-19, we’re going to need to keep working at elimination. Because our systems are so good now, we are able to track rare transmission events in ways other countries can only dream of. We’ve had what seems to be transmission in managed isolation from a bin lid and a lift button. Then we’ve just had the port worker who picked up the virus despite wearing PPE.

And now we’ve had several new arrivals in Christchurch test positive in managed isolation at their routine day three test. They are from a large group of workers from Russia and Ukraine who have recently flown to New Zealand on a charter flight to take up jobs on fishing boats. They all tested negative before flying. The first thing this highlights, yet again, is that just because people test negative before they board a flight doesn’t mean they aren’t a risk. They could have taken an unreliable test, or could be incubating the virus, or could have become infected on the journey. It’s just more evidence for why our border controls and managed isolation and quarantine facilities need to stay in place. And why we need to keep using all the slices of Emmental at our disposal.

No room for complacency

I’m noticing that complacency is starting to creep back in again. The number of people using the contact tracing app is dropping, just like it did before our second outbreak in August.

At the very least, we must keep up with washing our hands, practising safe cough and sneeze hygiene, wearing a mask, using the contact tracing app, staying home when sick, and getting tested if we have symptoms. That way, if the virus does get through our managed isolation and quarantine system, we’re far less likely to need to move up the alert levels to stamp it out again. Instead we can use testing, contact tracing, and isolation.

We’re in this for the long haul, and it’s up to all of us to play our part.