In the wake of this week’s news about Otago University’s art history programme, Francis McWhannell considers the current crisis in the arts in tertiary education and wonders whether we’re beyond salvation.

“The building is crumbling round us – which is scary, coz I just got in the elevator.” This comment was made to me the other day by fellow art writer Lucinda Bennett. Those of us whose careers are hitched to the visual arts are accustomed to thinking of our positions as vulnerable. The notion of the struggling artist, slaving away as a dishwasher to support her practice, is so well known as to be a cliché. But the struggling arts worker – whether a gallery assistant, auction house intern, or arts writer – is really just as common, as Bennett discusses in a recent think piece on the pervasive and perilous myth of ‘passionate labour’, work done for love rather than money in the arts and culture sector. Curators, directors, and technicians may be a little more stable in their incomes, but their positions remain precarious. Redundancy hangs over all of us like an Auckland raincloud. The question is not if it will burst but when.

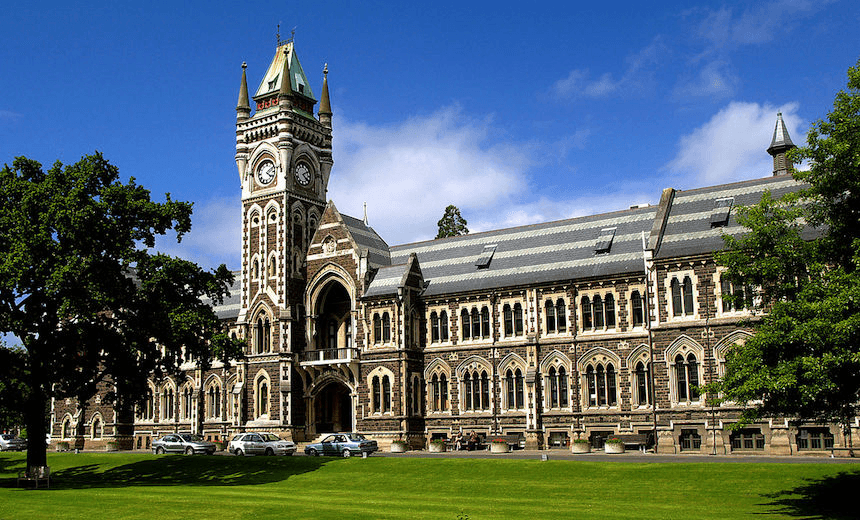

Were the problem restricted to the job market, or to the visual arts alone, things might feel a little less desperate. But the issue increasingly extends into higher education and into the arts more broadly. Having trimmed the equivalent of 16 academic jobs in the humanities in 2016, the University of Otago is now proposing to phase out its Art History programme. Arts jobs are on the chopping block at Victoria University of Wellington (though the institution claims there will be ‘no impact on students’). The University of Auckland recently confirmed that it would close three specialist libraries associated with the Creative Arts and Industries (CAI) faculty, merging their collections with that of the larger General Library. This last issue has received particularly extensive media coverage, including here on The Spinoff. Indeed, it has become the go-to example for many who feel that the arts are under attack at New Zealand universities.

I get it. As a Master of Arts candidate specialising in Art History, I regularly use one of the CAI libraries, the Fine Arts Library. Good liberal that I am, I’m horrified by the symbolic statement of disestablishing any library. By all accounts, consultation was scant, and dissent was promptly ignored. The university’s review offers at best weak justification for the decision, citing ‘steady decline in occupancy rates’, when in fact they’re fairly stable, and noting that the CAI libraries ‘do not meet the requirements for modern library and learning spaces’, when basically they’re as fit as any other on campus. The report also notes that physical loans have dropped at a lower rate than at other UoA libraries (this despite many resources being consulted on site), confirming what everyone engaged in visual arts research already knew: that physical items are still important, because digitisation has been slow and partial, chance encounter amid the shelves matters, and there is no single textbook for our work.

The University of Auckland has put forward another motivation for axing the CAI libraries: the need to save money. Coupled with the other justifications, this reason plays into the narrative, well-established in the arts and culture sector, that the free-market structures that have dominated New Zealand politics since the mid 1980s are all for eroding the humanities. The university itself has done little to dispel this notion. Rather ironically, since he is often characterised by detractors as a wicked implementor of an insidious neoliberal agenda, vice-chancellor Stuart McCutcheon recently commented that “for more than 20 years successive governments (on both sides of the House) have favoured policies that reduce the cost of university study to students and government, over policies that enhance the quality of universities.” In other words: Don’t blame us, blame the government and its refusal to stump up adequate funds.

The problem for those of us who work and believe in the arts is that the cost-cutting argument is backed up by irritatingly firm stats. The University of Auckland’s Key Statistics 2011–2016 show that enrolments in its humanities-focussed faculties – Arts, CAI, and Education – have all trended downward over the period covered, and noticeably. Law is down a bit. The most immediately market-friendly faculty, Business and Economics, is stable. But it’s Engineering, Medical and Health Sciences, and Science that are really on the up. Humanities faculties are not holding their own.

And the same is true at other Aotearoa universities. Flagging enrolments are the key explanation for the changes afoot at both Victoria and Otago. At the latter, for instance, enrolments in Art History have reportedly dropped by more than 75% since 2014, despite overall enrolment increases. And the problem is not solely a New Zealand one. American public intellectual Martha Nussbaum has gone as far as to declare “a crisis of massive proportions and grave global significance”.

Where did this crisis come from? For some years, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects have been touted internationally as the key to economic success, while the humanities have been dismissed or ignored. The University of Auckland’s Peter O’Connor has charged the former government with throwing its weight behind STEM subjects at the expense of the arts. The situation could, in theory, change under the current government, which is known for being pro-arts and pro-funding (having committed to offering all New Zealanders a fees-free tertiary education). Aotearoa universities tend still to avow their commitment to the arts (as McCutcheon has done), even if their actions tell a different tale. Those of us working within the humanities have always recognised the value of our work in enriching lives and in growing (to quote Nussbaum again) “complete citizens who can think for themselves, criticise tradition, and understand the significance of another person’s sufferings and achievements”. Increasingly, business – both here and abroad – is emphasising the value of arts subjects for their ability to yield workers who can think laterally, who are adaptable (all important in an ‘ever-changing world’), and who drive innovation.

An impediment to the flourishing of the arts at tertiary level might in fact be the public. In the visual arts industry, we’re all too familiar with the problem of the everyday Kiwi. As far back as 1945, A. R. D. Fairburn wrote that “a gulf yawns between art and the general public.” The surest response to the announcement of a new public artwork is “What a waste of tax-payer money!”, followed closely by “Elitism!” for any piece that dares to be even a little difficult to understand. Nevertheless, I suspect that the public is not per se against the visual arts (even if its tastes are more conservative than the art world’s), but that it considers them non-essential, feels no urge to support them. I dare say a similar situation obtains for the humanities more broadly. With the exception of the odd Hosking-ite, most people probably don’t mind that arts subjects exist. However, they don’t accord them particular importance, and, crucially, they don’t encourage their kids to study them. We’ve all heard that joke at the expense of the no-hoper BA student. We’ve all met that teenager who wanted to be a writer but whose dad insisted that Med School was the better option if she wanted to make ‘real money’.

In suggesting that the hoi polloi just don’t care enough for the humanities, I don’t wish to sell them too short. I’m sure there is the odd good dad out there who told his daughter to follow her dreams. Nor do I wish to imply that it’s all their fault. One of the roles of societal influencers like government and universities is to foster and promote what matters, and – where the humanities are concerned – both have been letting us down. At the same time, I can’t help but feel that we humanities professionals have been doing a less than adequate job ourselves. Perhaps if we were as effective at showing the wider community how and why our work is important as we are at whining amongst ourselves about mean and misguided money-men we might not have lost quite so many enrolments. (As the people behind much media and entertainment, you might think we’d be nailing self-promotion.) Although I do not wish to suggest that we ought to play by all the dodgy rules of the money-men, perhaps if we were more successful at presenting our sector as a site of critical thinking and innovation we might have seen enrolments grow.

I remain optimistic. But we’ve a big task ahead of us. Robust international models are few. But the solutions will no doubt need to be multiple and widespread. Perhaps it is time for a dedicated humanities hui, bringing together representatives from education providers, from government, and from professions with a declared interest in the arts. Up front, we must acknowledge that money speaks in our sector as elsewhere. The tightening of the screws has got to stop. We will need to actively invest in the humanities, whether through new grants and scholarships, new programmes, or the vigorous promotion of existing ones. Just as improvement of the public transport system in Tāmaki Makaurau led to growth in the appetite for such transport, so improvement of our arts facilities should lead to increased public support. For our part, humanities workers will have to remain open to ideas that might be unfamiliar. We might need to consider the creation of new faculties and hybrid qualifications (building on existing General Education and conjoint degree structures). We might need to forge stronger ties with entities outside the university – not only public institutions, but also private businesses.

It seems likely that we will need to look beyond the tertiary sector too. What can be done in primary and secondary education to foster a belief in, and love of, the humanities among the children who will ultimately be making the decision regarding what university courses they take? Are we overdue the development of a civics programme in New Zealand schools? How about history and cultural studies? Do our children exit school with an adequate sense of what it means to live here, in Aotearoa? What sort of society might result from an education system that from day one treated the arts as just as valuable as the STEM subjects, that truly took as a priority the cultivation of rounded citizens. As Nussbaum notes, “Of course you need to produce people who are computer scientists and engineers, but why shouldn’t they have years of general education where they learn things that equip them for citizenship and life? They’re going to be citizens too whatever else they are.”Am I lapsing into too much lofty idealism? Is this something we could sell New Zealand on? Maybe we just haven’t tried hard enough yet. Maybe the building just needs some reinforcing.