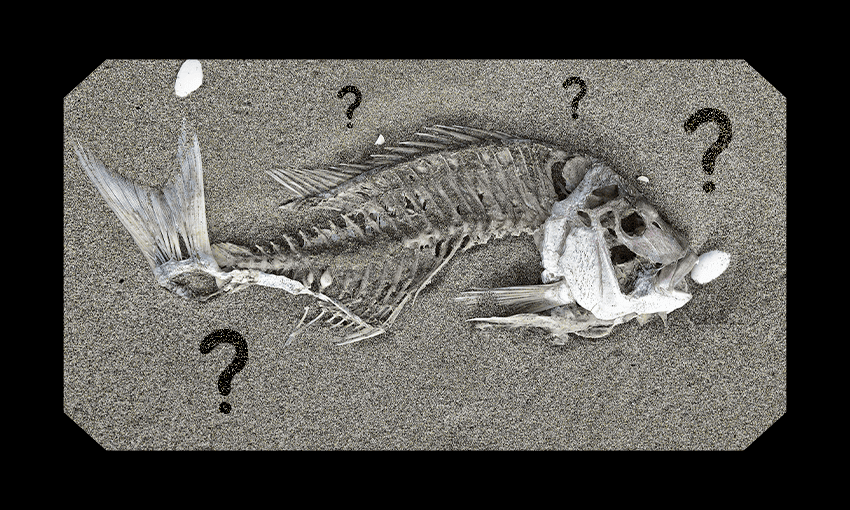

Intensive commercial fishing has depleted the food sources of the snapper of the Hauraki Gulf, resulting in a fish population that is seriously unwell. We need to act now if the ecosystem is to recover, writes Sam Woolford.

Mushy, white-fleshed snapper have been a hot topic over barbecues, bait boards and beers in the north of the country for some time, and it seems there are more theories on the cause and remedy than there are snapper.

The way in which we are commercial fishing, the amount of baitfish we are harvesting and our lifestyle have resulted in the large-scale depletion of important food sources that have historically sustained snapper and other finfish populations.

Each year, we’re used to seeing spent fish after the snapper spawning in spring. The fish normally take a few months to recover. What is unusual now is that people have been catching mushy-fleshed snapper since before the spawning season. Now, coming into winter when the fish should be in good condition, there’s still lots of mushy fish about.

Through the LegaSea Kai Ika Project, we fillet fish for recreational fishers and distribute fish heads and frames to local marae in Tāmaki Makaurau. We have been monitoring this mushy-fleshed condition for almost a year. The rate of mushy flesh fish averages 20% of the fish we fillet. That’s one in five fish. This indicates a fish population that is seriously unwell.

LegaSea has received reports from MPI and Fisheries New Zealand, including the Biosecurity New Zealand report, which make some alarming findings on the state of our snapper:

“Degenerative changes in skeletal muscle [of snapper] relating to muscle atrophy and a loss of polysaccharides [carbohydrates] within muscle tissue, [are] associated with tissue breakdown following a prolonged period of starvation.”

“The iron accumulation seen in the affected snapper is attributed to chronic starvation, tissue breakdown (releasing iron from cells) and poor haemostasis [no blood flow] of iron in the body and tissue.”

It’s simple: when an animal doesn’t have enough to eat, it starves.

It’s not just our observations. The government reports point to muscular atrophy as the cause of white mushy flesh. But snapper are scavengers, incredibly hardy and eat almost anything. So the mystery is, what does a snapper eat and where has all the food gone?

In reality, there are numerous factors at play. The Hauraki Gulf marine park has been intensively fished for decades. The figures published in the 2020 State of the Gulf report say it all:

1. There has been a 100% reduction in wild mussels. It’s well documented that 500 km2 of mussel beds were destroyed in the 1960s by commercial dredging. The only remaining wild mussels are found in the intertidal zone.

2. The commercial harvest of blue mackerel has increased by 470% since the park was established in 2000. Between 2016-19 the commercial industry extracted a staggering 9,000 tonnes of blue and jack mackerel from the Park.

3. There has been a 57% reduction in the population of jack mackerel and a 32% reduction in other small pelagic species.

4. And, 376 tonnes of pilchards are harvested annually from the park.

Individually, each of these statistics is alarming. But the real concern is the fact that these species are the food sources for seabirds, mammals, john dory, kingfish, kahawai and, of course, snapper. Without these keystone species, the ecosystem will be dramatically different, or species will cease to exist altogether.

So, what do we do with the vast amount of mackerel that is bulk harvested every year? We export it frozen and unprocessed to Ivory Coast, Philippines and China for an average price of $2.30 per kilo. Is it worth starving our snapper for $2.30?

If removing vast amounts of baitfish is not enough, the preferred commercial harvest method for many finfish species is bottom trawling. Bottom trawling requires dragging large nets and sleds along the seafloor. This crushes the crabs, mussels, invertebrates, and other species. Once again, these are sources of food for snapper, trevally and other fish.

To add insult to injury, there was an emergency closure of the last remaining viable scallop beds off Little and Great Barrier last year. Until then, scallops were commercially harvested by dragging a huge Victorian box dredge along the seafloor. Again, this harvest method decimates seafloor life, further reducing food sources for our snapper populations.

After decades of dragging nets and dredges along the seafloor, we have removed the biodiversity. Now there are large areas devoid of the very food source that our coastal fish populations require to survive.

Finally, the shellfish beds in the intertidal zone are smothered by heavy metals and land-based runoff.

The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park surrounds metropolitan Auckland and the Coromandel. This is the biggest concentration of New Zealanders in the country. Historically, after spawning, snapper would swim into the shallow warm waters and feed on pipi, cockles and mussels. Many of these shellfish beds are now gone because of over-harvest and the amount of land-based pollution running into the gulf. Just imagine, if beaches are unsafe to swim at after heavy rain, what impact is that having on marine life?

It’s clear we are having a sustained and cumulative effect.

Sadly this is not a new phenomenon. The food sources in the marine park have been depleting over the decades. Reports of starving snapper have been around for years. It’s just never been seen on such a scale before. For those on the water this is a well-known issue. Ultimately policymakers have ignored concerns citing the need for economic gain rather than environmental wellbeing.

By systematically taking away all the food sources, the cupboard is now bare. We have produced the perfect storm.

If we are serious about resolving the mushy-fleshed snapper issue, we need to first acknowledge that our snapper are starving.

We need to adopt a precautionary approach. It is clear that it’s time to act. We need to ban bottom trawling, scallop dredging and Danish seining. We need to transition commercial fishing to longlining. It is much less destructive and more selective. Stop the commercial exploitation of keystone species, including blue mackerel, jack mackerel and pilchards. Finally, we need to protect the remaining intertidal shellfish beds with an immediate ban on all harvest. These are obvious actions that need to happen now.

If we take the pressure off, ecosystems are remarkably resilient. But, they will also take time to recover from this prolonged abuse. We need to act now and, at the same time, be patient.

Finally, why go to all this effort? Simple, our goal is to leave our coastal fish populations in a better state for our children than what we have inherited.

Sam Woolford is programme lead at LegaSea, a non-profit organisation dedicated to restoring the abundance, biodiversity and health of NZ’s marine environment.