In August a group of New Zealand researchers presented a report to the UN detailing the effects of racism on Māori. Simon Day spoke to AUT’s Dr Heather Came about the causes and cures for New Zealand’s racism.

When Dr Heather Came listened to the New Zealand government delegation present to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) she was surprised to hear New Zealand was apparently doing well for its indigenous people and ethnic minorities. In her research Came had learned the exact opposite.

“When I sat there and listened to the New Zealand government do their spiel it felt like they put up a tourism brochure, written by PR people who have never been to New Zealand. I don’t know how such intelligent senior public servants could deny the institutional racism that is prevalent in their administration of the public sector. It was quite a bizarre experience to see that,” says the AUT senior lecturer in public health.

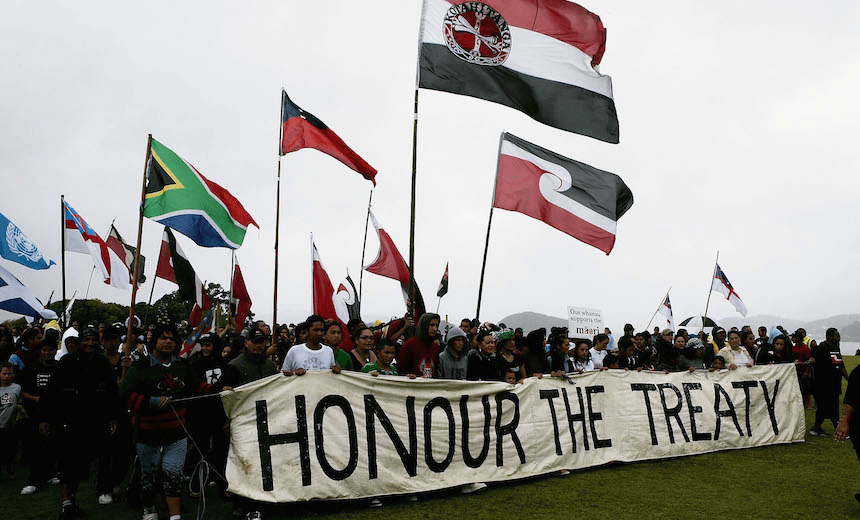

Came had the chance to give the UN a different perspective. A group of nine institutions working with public health and Māori presented a report to CERD on 20 key issues where institutional racism is affecting outcomes for Māori in New Zealand. It condemns the absence of the Treaty of Waitangi in public health policy, the way Māori are portrayed in the media, and the deep institutional racism of the public health system.

It also offered the government solutions to this systemic racism. They’re solutions that engage the potential of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi to improve outcomes for Māori, and embracing the potential of a Māori worldview to contribute to health policy. But first Pākehā New Zealand needs to accept and acknowledge this problem exists.

Your bio lists you as an activist scholar; what is an activist scholar?

An activist scholar is a particular methodological approach where you generate your research topics and dialogue with activists to advance political goals. It is political research but it is particularly rigorous research because you anticipate others accusing you of bias.

Where has that lead you?

I’ve been an activist all my life. I’ve only more recently, accidentally become an academic. The focus of my activism is Treaty work, anti racism work, and that means I’ve been working with Māori for a long time and trying to advance Māori aspirations in the context of health, by clearing out of the way some of the obstacles to Māori success and flourishing, which is of course the institutional racism of our government.

How is Te Tiriti o Waitangi powerful for realising these ideas and better outcomes for Māori in general?

It is the terms and conditions by which my ancestors came to this country, so it is incredibly personal. But also as a public health practitioner it is essential to our ethical practice that you engage with the Treaty.

My understanding is that Māori entered into that agreement with the British to advance their aspirations, it was strategically beneficial. It affirms tino rangatiratanga. It promises equity. It is something that I think about, and work with.

Do you think the importance, and the power and potential of Te Tiriti is widely recognised?

We’ve got a paper that’s coming out in the New Zealand Medical Journal, that looks at public health policy over ten years, from 2006 – 2016, looking at how they talk about either The Treaty of Waitangi or Treaty principles. We found 49 policy documents, and only 12 actually mention it. Given the relevance of Te Tiriti to health, and the work of Mason Durie and others, that have shown this time and time again, I don’t think we are giving nearly enough attention to the Treaty in meeting our obligations.

That is particularly obvious when looking at the Wai 2575, the health related Waitangi Tribunal claims, which are currently beginning to go through the Waitangi Tribunal. And there are over 100 of them, citing examples of when the minister of health, or senior crown officials have breached the Treaty of Waitangi. That is not something the health sector should be celebrating. There is clearly more we should be doing or there wouldn’t be all of those deeds of claim being processed at this time about historic and contemporary breaches of the Treaty.

I would argue there continues to be breaches. We haven’t stopped breaching Te Tiriti. Māori are our Treaty partners and that’s different to some low level stakeholder that you need to consult with. These are people you need to make decisions with, these are your partners.

If you are honouring Te Tiriti you are sharing your power, and there should be no evidence of institutional racism in how you make decisions and in your practices.

What inspired the decision to take the shadow report to the UN? It seems like a really big deal that this is where it got to. What does it say about the state of racism in NZ?

Listening to the New Zealand delegation speak in Geneva I think they believed their own propaganda. I think they believe they are doing really well.

We went because we wanted to challenge what our government was saying. I think we were heard and the UN committee agreed with us that we weren’t doing as well as we could. It means that forever it is on the record that we disagree, that it isn’t all rosy, because it isn’t. Currently, the human rights of Māori in New Zealand aren’t being protected.

It was the first time we had such a big health sector report, because we had a whole lot of different agencies that stood with us and put forward evidence to go into our report. We will be reporting in that forum and in that setting, until the New Zealand government, the ministry of health and the DHBs, and the other people that shape the health sector, are compliant in their delivery to Māori.

What does institutional racism look like in New Zealand?

Institutional racism is a pattern of behaviour that disadvantages one group while advantaging another. So there’s always a flip side. Whenever there is racism, there is privilege.

Lots of our work has been documenting the institutional racism in the health sector. My PhD looked at policy and funding practices – I did a nationwide survey and looked at Māori health providers’ experiences of Crown funding. We compared this with the experiences of primary health organisations, other non-governmental organisations, and public health units that are based in DHBs – mainstream providers. What we found was that across those different providers, in terms of factors like the length of their contract and the frequency of how they were scrutinised, there were a whole lot of domains where we could show statistically different treatment of Māori health providers – and that treatment was negative. That was an example of the racism.

There was no justification if you read the policy documents, and frameworks, and how the ministry of health or the DHBs are supposed to be doing procurement, there is no explanation for why they would be giving Māori shorter contracts than other providers. There are a whole lot of places where you can identify this racism.

How does institutional racism manifest itself for individual experience, once it reaches the people?

Our work is about the structural stuff. Other people like Ricci Harris at Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare, have done a lot of research around what happens when people are trying to access health services. They’ve done research that shows if you turn up at A&E and you’re Pākehā, and you have a set of symptoms, and you turn up at A&E and you’re Māori with the same set of symptoms, you will get offered different treatment plans. You will get offered more expensive stuff, and more aggressive stuff if you’re Pākehā, because there are assumptions about how motivated your family are, or what resources you have available to care for yourself. The failure of screening programmes to reach Māori and Pacific communities means they miss out on early protection, and that impacts on their health outcomes.

My discipline is public health. And that is about keeping whole populations well. We are the people that try to get people to wear seatbelts, we are the people that try and stop people from smoking, we’re the people that are interested in ending poverty because it is a key determiner of health. So we are interested in groups of people rather than individuals, but you can see the reach of institutional racism across all sorts of domains.

Do you think New Zealanders are aware of the extent that racism exists in our country?

I think racism has been normalised, so it is often hard for Pākehā to see the racism. We are enormously monocultural in how we conduct ourselves.

I think we could do much more, for example by making te reo Māori compulsory in schools and helping encourage and nurture people to learn more about te ao Māori. Certainly for me, my contact with te ao Māori has been really positive – I’ve learnt lots of amazing things about this land and the people who live here that make me feel a fuller and more useful human being. I think there are lots of opportunities to learn from te ao Māori.

In the last few weeks we have seen the commentary that’s labelled the Treaty a cover up and complained about hearing te reo Māori on the radio. What effect do comments like that have on Māori, and the success of New Zealand?

I think it is great if people can take the time to read the text of the Treaty and take the time to learn a bit about our colonial history. If we believe in fair play, which I believe many New Zealanders do, we need to come to terms with the impact of historical racism on this country. If we manage to stop the racism in this country and improve the health and educational outcomes of Māori, we will lift up the health and well being of all New Zealanders. It is in our best interest to support Māori taking control of their health and well being.

What needs to be done to make that happen and what role would the Treaty have in that?

I would love every New Zealander to spend a day going to the Waitangi Tribunal hearings, and listening to the evidence and getting a bit of the sense of what happened. I went to the Wai 1040 claims up in Nga Puhi because I was living there at the time. There wasn’t many Pākehā there, but it was very humbling and interesting.

From my understanding of a Māori worldview, the past is before us – it is not tucked away, it is forever present. The way Māori were talking about Te Tiriti at that hui I was at, it was as if it was signed yesterday. For a lot of Pākehā people, 1840 is ancient and buried history.

We have an opportunity to choose to engage with Māori going forward with integrity and honourability going forward, and to honour the agreement that my ancestors made on our behalf. That is an approach of integrity and fair play – and that is a more useful way forward than burying it and pretending it never happened.

We can make this right, if we have the political will to do this. For a lot of Pākehā family like mine, my god daughter is Nga Puhi, I am a seventh generation Pākehā New Zealander, my nieces are Ngati Maniapoto and Ngati Whatua, my grandchildren are Ngati Kahungunu. This is the future of Pākehā that we are going to have this blended whakapapa.

There are a hundred reasons why we have to come to terms with what’s happened in this country, and try to end the institutional racism that we have. Let’s not be a divided country, but instead a country that is rich in equity.

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university, we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.