Yesterday’s Extinction Rebellion protests may have caught the media’s attention – including The Spinoff’s – but do such small-scale disruptive events actually do more harm than good?

There’s something beautiful in the air. People are striking and protesting in numbers unheard of for a generation or longer. Issues like inequality and climate change have reached crisis point and ordinary New Zealanders are mobilising around them, in numbers and networks beyond the subcultural activist ghetto that provided the usual suspects to the demonstrations of yesteryear. It’s an exciting development that offers us hope for much needed social change.

I totally support the cause of Extinction Rebellion and fervently rang my bike bell in solidarity as I passed them yesterday morning on my way to work. Nonetheless, a discussion is needed about which tactics work best, and how we win people over to support our values and inspire them to take action around them.

Spokesperson Sea Rotmann told Radio NZ yesterday morning: “Going on the streets, and disrupting the process, enough that people are willing to engage with how bad the problem is, is the kaupapa of Extinction Rebellion and it’s been very successful so far.”

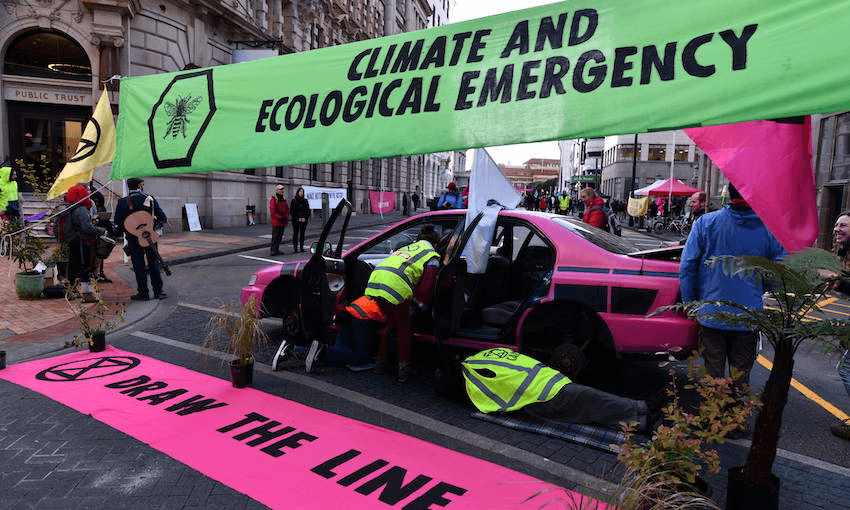

Statements like that are worrying. What process was disrupted? Not the profit-gathering process of the energy companies, nor the other processes by which the corporations destroying our planet go about their dirty business. As far as I can tell, small groups of protesters caused traffic jams while waving banners with demands around climate action. The goal is to gain media attention firstly and attention from commuters and the general public secondarily. The means is disruption, primarily to the previously mentioned commuters.

But does this work? Everyone is already aware of climate change, if anything they’re bombarded with awareness. I suspect most people switch off and attempt to live in denial about it, as a survival mechanism for getting through the day.

If those already convinced of the need for climate action must reach out to and win over the huge group wavering in the middle – aware, but inactive or unsure what is to be done – in order to isolate and politically defeat the reactionary backward minority of climate change deniers and big business acolytes, do we do so by deliberately inconveniencing ordinary people in their thousands, though the dedicated efforts of small groups of protesters? Is this effective political action, or substitutionism that risks backfiring?

There is sometimes an assumption that media attention around activists doing things is always good and useful. It’s easy for us to not realise we’ve alienated people while the endorphins are flowing after an exciting demonstration, but footage of roadblocks during rush hour will quite simply piss a lot of people off.

Are we sure that in exchange we will win over a worthwhile number of people who didn’t already agree with us and weren’t already prepared to act?

Contrast the actions of Extinction Rebellion with the tens of thousands who marched the week before last in the School Strike for Climate. That also shut down the city, in an ultimately even more disruptive way, but it did so via an undeniable display of mass support and people power. Those who weren’t already on board were confronted with evidence they may be on the wrong side of history, that the world and popular opinion may be passing them by. I’m not convinced the same reaction will be achieved when footage plays of 50 to 100 people blocking an intersection.

I spent many years involved in relatively small protest actions carried out by committed activists in order to gain media attention and reach the public that way. It was a hard lesson to learn that this is as likely to piss people off and push them away from you as it is to convince them of your argument. Small protests are often driven as much by passionate activists’ need for catharsis as by any concrete strategy.

Peter McKenzie argued in September that “disruptive” tactics like those of Extinction Rebellion are a necessary step beyond mass demonstrations and rallies, but I’m not so sure. There is a negative trend in the history of social movements in which the organisers of mass demonstrations grow frustrated with the pace of change, lose faith in the political agency of ordinary people, and instead substitute for mass community action an ever more radical and ever more isolated series of direct actions.

A useful example is provided by the story of Students for a Democratic Society, an American political movement which at its height in the late 1960s could mobilise tens of thousands of supporters. Student strikes against the Vietnam War paralysed campuses across the United States, but the leadership of SDS became convinced this was not enough, went on to dissolve their own organisation by fiat and formed the Weather Underground.

The ostensibly more radical organisation declared itself to be on a war footing with the US government, aiming to bring the Vietnam War home and confront politicians, cops and the general public with militant and even deadly political action that would blow the wax from their ears. In reality, SDS chapters collapsed in disarray across the country, the Weathermen (as members of the Weather Underground were known) succeeded only in blowing the bodies of their own members apart in botched bombings, and the former leaders of a mass movement found themselves underground, on the run and disconnected from any ability to reach the public. The main thing disrupted by their new strategy was their own capacity to be politically effective.

This is not to suggest that McKenzie is encouraging the leaders of Extinction Rebellion to go down the same failed road of urban guerrilla action. The new generation of activists are firmly committed to non-violence and remain convinced, for now at least, that the New Zealand public can be won over. However, the political analysis he puts forward is remarkably similar to that on display when SDS tore itself apart. Political change takes time and a tremendous amount of effort, and with climate disaster looming it would be easy to conclude time is the one thing we don’t have and the effort can come from an enlightened few prepared to put themselves on the line.

To come to this conclusion would be a serious mistake. People are currently flocking to the banner of climate justice in unprecedented numbers. Hope lies in this trend, and we must do nothing to jeapordise it. A hundred or even a thousand activists cannot act on behalf of the ordinary people who make society’s wheels turn, bringing about transformational change without mass involvement from the working class. If those wheels are consciously brought to a halt, however, everything is on the table.

This is the difference between disruption and politics. Between media spectacle, and the collective power of the people.

Perhaps rather than disruption for its own sake, we should ask ourselves who we must disrupt in order to change the world. Working people driving to the office, or big business at the point of production? And perhaps rather than seeking media attention for its own sake, we should ask ourselves: who do we want to see us, how can we be seen in a way that makes them more likely to listen, and what action are we asking them to take?

If the answer to the latter question is that we ask them to come along to the next protest, further questions become necessary. Do we have a strategy to challenge power and win? Or do we risk creating a self-perpetuating cycle of protests by a passionate activist minority, that industrial capitalism has historically shown itself to be very adept at co-opting and neutering over time?

Our tactics must be carefully designed to bring the greatest number of ordinary people along with us and into action with us. They should not target or negatively impact the lives of those same people, our key audience, in what can at worst become a patronising effort to ‘wake up the sheeple’. We need no condescending saviours.

The politics of spectacle are a risky business. Tears ran down Greta Thunberg’s face as she passionately denounced the criminals destroying our planet to their faces, and without irony they applauded her. Being seen is not enough. We need hundreds of thousands walking out of schools and workplaces, not dozens blocking a road at rush hour. We need to strengthen the alliance between the climate movement and the industrial power of organised labour. We need to ensure the rapacious elite destroying our climate not only hear us but fear us as well. All we will ever have to make that happen is numbers; we are many, they are few.

Alastair Reith lives in Wellington, where he works for the Public Service Association. All views expressed here are entirely his own.