In recent years, checking online for a green tick has become a necessary habit for Aucklanders heading to the beach. Shanti Mathias tags along with the team tasked with testing the water for pollution – and figuring out how to stop it.

“We get to be poo detectives,” Stephen Ashley says. This is how the water quality specialist at Auckland Council explains his job to other people. His idea of a good – although often gross – puzzle to solve at work is someone else’s idea of very bad news for their after-work swim plans.

The sun is shining and the sea is sparkling at Castor Bay, a beach next to Milford on Auckland’s North Shore, but Ashley, a lean Pākehā man with a practical wide-brimmed hat, is more interested in what’s going on at a microscopic level: how much bacteria might this innocent stream outlet pipe be sloshing across the beach, currently mainly occupied by squawking gulls and a single swimmer? And where did those pathogens come from?

His colleague Martin Neale, Safeswim’s technical lead, bends down in the sand and starts drawing a branching diagram with his finger. “The contamination might be here, or here,” he says, circling nodes in the branches. “It’s like a process of elimination.”

Ashley shows me the more professional equivalent of the branching diagram – an app used by Auckland Council’s Safe Networks team, which monitors water quality in streams, watercourses and the stormwater network to identify the sources of contamination.

This monitoring is vital work, because Auckland’s beaches are frequently so polluted, mostly by human waste, that swimming in the water poses a danger to human health. Last year, a major sewage pipe burst discharged thousands of litres of raw sewage into the water in Parnell, rendering most inner-city beaches dangerous for weeks. (“Seeing it caused me to lose a bit of faith in humanity, to be honest,” Ashley mutters). But most of the contamination is less dramatic: rain can cause wastewater and stormwater to mix in older sewage systems, so many beaches are reliably unhealthy after rain.

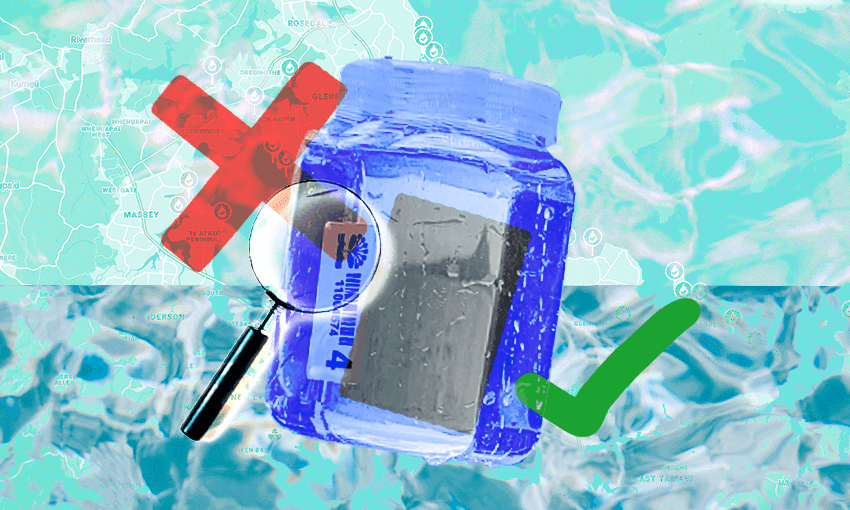

Safeswim, a collaboration between the Auckland and Northland Regional councils, Watercare, Te Whatu Ora, Surf Lifesaving NZ and Drowning Prevention Auckland, is one part of the solution: to stop people from getting sick, simply provide advice about when not to go in the water! The app and website use a mix of sampling and an algorithmic model to alert people in Auckland and Northland about the water quality at their local beach with a colour code system. Green means a beach is clean and the risk is low, red means there’s a high risk, and black means there’s a direct wastewater overflow affecting the water.

Ashley’s detective work – part of the council’s Safe Networks programme – is another piece of the puzzle. If a beach is contaminated when it hasn’t been raining, it’s particularly concerning, but it’s also an opportunity to isolate the cause. They take samples at every branch of a stormwater pipe, or their more old-fashioned equivalents, streams, to isolate the source of pollution. It might be one particular house or outlet pipe that can then be fixed. If there are consistent quality issues that they can’t explain, then they will put the beach under a long-term health risk alert on the Safeswim website.

“It’s nice when it’s an issue that can be fixed quickly,” Neale says. More structural problems – like the ageing water infrastructure – take longer, although solutions like the $1.5bn Central Interceptor pipe should help. Meola and Te Auaunga creeks in Central Auckland have long-term alerts, for instance, although that should change with the Central Interceptor.

But before an investigation can take place, the water needs to be sampled. Ashley has already changed into his sand shoes and is walking to the edge of the water grasping a little plastic jar. He takes note of the number of dogs and people on the beach, the weather conditions and the birds, all factors that can contribute to the water quality reading.

The Safeswim team tries to take samples at times when people actually swim, so at muddy beaches there’s not much point wading across hundreds of metres of sediment to get to the water at low tide. They have “runs” of beaches, 10 to 20 sites that one of the small sampling team might get to in a day, although some beaches – like those on the islands of the Hauraki Gulf – present more of a logistical challenge. Waiheke is doable with the ferry, a contractor on Great Barrier couriers samples to the lab on a plane, but it’s much more time consuming to get to the other islands. Ashley’s favourite runs are on Waiheke and along the rural beaches from Te Ārai Point north of Auckland.

“I’ll just demonstrate a sample for you,” he says now, splashing into the water, aiming for about knee depth. He scoops water into the jar, then screws on the lid. When he’s back on the beach, we inspect it together. There’s not much to see, as it’s perfectly clear. “It looks good enough to drink!” Martin jokes, then adds more sombrely: “I’ve seen samples like that come back from the labs and been astounded by the numbers.” Ashley did his masters in water-borne pathogens that affect mice. “I found that it had to get to 10 million bacteria [in a sample of this size] before it would be visible to the naked eye.” The swimming guidelines say that there is some risk once there are more than 260 E. coli in 100ml of water, so clear water is no guarantor of safety.

After taking a sample, it’s placed in a chilly bin so more bacteria don’t grow and throw off the results. Then it’s taken to the lab where the sample is tested, which takes about 24 hours; the result then needs to be checked by one of the scientists before it can be compared to the national healthy swimming guidelines and fed into the Safeswim’s database. At Castor Bay, Ashley tells me the beach was sampled two days previously but the result isn’t in yet.

This might sound slow, but the system doesn’t rely on sampling alone. The data gathered at Castor Bay is a tiny fraction of the amount of information that is required to run the Safeswim website. “Taking a sample once a week doesn’t give you a very accurate read,” Neale says. “We’ve made a huge investment in sampling – but it’s more important to look for patterns.”

They need at least 50 to 100 samples from a beach, in a range of weather, before they can include it on the website. Beaches get their status based on past patterns, as well as sensors that detect rainfall around the region; it could be that whenever there is more than ten millilitres of rain in an area, a pipe leading to the beach will overflow, so a warning will appear on Safeswim before it’s been sampled.

Tide movements, currents, levels of rainfall, watersheds and locations of stormwater drains: these are all built into the Safeswim model to provide accurate water quality forecasting, faster than any lab alone could deliver. Neale calls it the “best available information on water quality and safety”.

Safeswim gets plenty of petitions to add new beaches, but they need to be able to accurately predict water quality in addition to having a base of information from sampling before a location can be added, which is why lots of samples are necessary first. Watercare, which manages Auckland’s water network, works closely with the Safeswim team, and has sensors to detect sewage overflows.

For the most part, contamination is predictable. Neale shows me a sheet of data for Castor Bay, dating back to 2019: there have been 11 times when bacteria levels have exceeded guidelines. Two of those were during dry weather, rather than as a direct effect of rain – the kind of results that prompt urgent second samples to check results and one of Ashley’s poo investigations.

As water activists have pointed out, simply telling people when it’s unsafe to swim can’t fix the chronic contamination on beaches. But does Safeswim actually change how people behave? That’s the hope: signs on beaches are usually ignored or taken down, but if people check Safeswim before leaving, it might divert them to one of the healthier beaches.

According to research from Auckland Council in 2023, 84% of people said Safeswim impacts whether they get in the water, and there has been a 134% increase in visitors from 2020 to 2022. “No one will physically stop you from getting in the water: [Safeswim]’s just advisory,” Neale says. “But people tell me all the time that that they go to Safeswim to select the best beach to go swimming at.”