On March 9 2020, the first Covid-19 collaboration by Siouxsie Wiles and Toby Morris was published. Twelve whiplash months on, Siouxsie ranks the good, the not so good, and the downright ridiculous.

Our Covid-19 coverage is funded by The Spinoff Members. To help us stay on top of this and other vital New Zealand stories, please support us here.

Today is a bit of a momentous day for me. It’s the one-year anniversary of The Spinoff publishing the first animation Toby Morris and I created together. You might remember it. It was called Flatten the curve and was based on a picture I’d seen shared on Twitter. I thought the concept was really important – that we should try to keep Covid-19 cases low so they wouldn’t overwhelm our health system, something we had seen happen in China and was happening in Italy at the time. But what struck me about the original was that it didn’t show how our attitude and actions could help. This is where, as a long time admirer of Toby’s work, I thought he could help. So, I asked Spinoff editor Toby Manhire if he thought the other Toby would be interested in working with me. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Nothing could have prepared me for the journey since. Our version of “Flatten the curve” was an instant success. The first tweet I sent with it garnered over six million impressions. Jacinda Ardern used it at a national press conference. The Washington Post, Buzzfeed and Wired shared it. NBC News called it “the defining chart of the coronavirus”. It went, pardon the pun, viral.

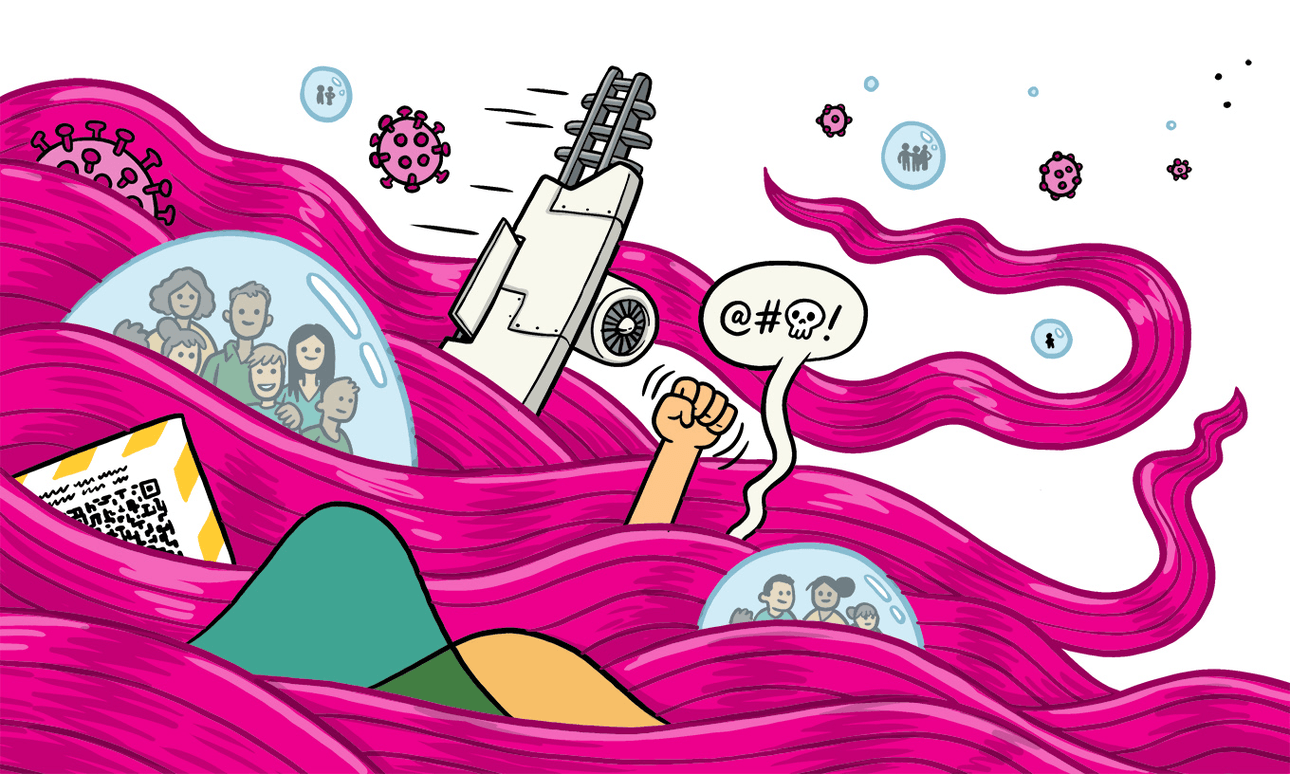

One year on from “Flatten the curve”, it seems a good time to reflect on my ride on what director general of health Dr Ashley Bloomfield recently described as the rollercoaster we didn’t buy a ticket for. And as The Spinoff is famous for its rankings (be it biscuits, Zoom backdrops used by members of the New Zealand parliament, or creatures from the Hairy Maclary universe), why not do it as a listicle of the good, the bad, and the ugly from my first year (and a bit) of the pandemic? Yes, I know, to rank these things is to a large degree an arbitrary exercise, but let’s try anyway.

10) Going viral with the wrong message

Ironically, that “Flatten the curve” graphic is my biggest personal regret of the pandemic so far. It sent the world the wrong message. We didn’t need to flatten the curve. We needed to smash it. Almost immediately, Toby and I started working on a new graphic, this time based on a paper published in the prestigious medical journal the Lancet. We wanted to show how with strong collective action we could eliminate the virus. But we’d also need to keep up our efforts. If we took our foot off the brakes too soon, cases would start rising again. Just five days later we released ‘Stop the Spread’. Unfortunately, this one didn’t go viral. I wonder if things might have been different in some countries if it had. Maybe. Maybe not. But I’ll always wonder.

9) Covid-19 isn’t ‘just a bad flu’

I can’t quite believe that one year later some people are still comparing Covid-19 to the flu. To date, worldwide, there have been over 117 million confirmed cases and over 2.5 million deaths. Both of those numbers are underestimates. The numbers are so big now, we’ve become numb to them. But every death was a person living their life, with hopes and ambitions, and friends and families that are now grieving them. Every case is someone who may still not even be fully recovered. Who may never fully recover. A recent small study found that about a third of the recovered cases they followed up with still had at least one symptom, usually fatigue or a loss of sense of smell or taste, months after they were first infected. And that wasn’t just in people who were hospitalised with Covid-19. The study also included people who’d had a mild infection.

There was a really interesting study published recently that tried to measure not just deaths from Covid-19 but the years of life that have been lost. That’s the difference between an individual’s age at death and their life expectancy. The idea is that if people are relatively old when they die, there will be fewer life years lost when compared to people who are much younger when they die. Their analysis goes to January 6 this year and covers nearly 1.3 million deaths. Based on that data, they estimate that globally more than 20.5 million years of life have been lost to Covid-19. The average years of life lost per death is 16. The average age at death from the whole dataset was 72.9 years.

But globally, just a quarter of the years of life lost come from people over the age of 75. Almost half the total comes from the deaths of people between 55 and 75 years old, and the rest from people younger than 55. It’s worth pointing out that the number of confirmed deaths is now over 2.4 million, so their results will already be a massive underestimate.

Yeah, Covid-19 is definitely not “just the flu”.

8) Haters gonna hate

As a woman with opinions on the internet, I’ve obviously come across haters before. But it didn’t prepare me for what I’ve experienced over the last year. Some days the deluge of hate has been overwhelming. I’ve had threats and hateful messages via email, text, my work voicemail, as well as on social media. I’m a fat pink-haired witch. A clown. A Satanist. A Covid celebrity. There’s even a guy in Dunedin who thinks I’m lying about my PhD because he can’t find it on the internet. The thing is, I haven’t done anything wrong. So, I’m just going to keep being me, and try to remember that while they may be loud, the haters are in the minority.

7) Becoming embroiled in a Covid conspiracy

The last thing I could have imagined a year ago is that my love of fireflies would leave some people believing I was a Satanist and part of a global conspiracy codenamed “luciferase” in which Bill Gates aims to microchip the world’s population. The evidence? Well, first is the fact that my research involves taking the genes that glowing creatures like fireflies use to make light and putting them into nasty bacteria. Those genes code for enzymes called, wait for it … luciferases. And the chemicals those enzymes work on are called luciferins. They both get their name from the Latin word for Venus, lucifer, which means light-bearer. The second piece of “evidence” is the fact that more than 10 years ago I was part of a Gates Foundation-funded research project to make the bacterium that causes TB to glow in the dark. Well, that settles it, obviously. The third bit of evidence is that I own a company called Lucy Ferrin Ltd. Lucy Ferrin. Get it?! Never did I think that pun would cause me so much hassle.

6) ‘Building the plane while flying it’

That was a phrase coined by a friend of mine at Harvard, Associate Professor Bill Hanage. It so well describes the situation we found ourselves in a year ago, and to some extent are still in. With Covid-19, we are trying to understand and respond to a virus and disease we’ve never encountered before. So, we are constantly having to make judgements and decisions based on the best evidence at hand and on our values. Because Covid-19 is so new, much of the early evidence we used was based on viruses like influenza and the coronavirus that caused SARS. But as the pandemic has progressed, so has the science, and as the evidence has changed we’ve adjusted our response. To some people this has looked like the experts don’t know what they are talking about. In actual fact, this is what science is like. Scientists are supposed to change their mind if the evidence changes. Beware those that don’t. A year on, there are still many gaps in our knowledge. And there are new variants of the virus evolving. That means we’ll need to keep following the evidence and adjusting our response accordingly.

5) Science at its best and worst

Speaking of science, the pandemic really has shown us the best and worst of research and academia. At its worst we’ve got medical doctors and people with PhDs ignoring and cherry picking evidence to argue that we should just be protecting the vulnerable and learning to “live with the virus”. That the pandemic is manageable by the herd-immunity-by-infection route. It’s bollocks. Not only is it bollocks, it’s unworkable, unethical, and eugenicist, and ignores the massive toll so many countries who’ve followed that model have paid, for no benefit. What’s depressing is that these arguments are being used to undermine efforts to aim for #ZeroCovid.

We’ve also seen research groups pivot their time, energy, and resources to trying to answer the unanswered question we have about the virus and to race to develop effective treatments and vaccines. That we are already vaccinating our border and MIQ workers with a vaccine that has been shown to be safe and effective is a testament to what can be achieved when the world puts its mind (and its money…) to it.

4) The importance of leadership

For me, this past year has really shown just how important good compassionate leadership is. I’m so grateful we had a prime minister and a government who decided that it was unacceptable to allow people to die just for the sake of the economy. In doing so, they’ve shown that a good health response is also good for the economy. When we entered our alert level four lockdown in March 2020, a journalist from the UK asked me why New Zealand had acted as it did. What evidence did we have that others didn’t, they asked? It’s quite simple really. We all saw what had happened in China and was happening in Italy and Iran. We all had the same evidence. We just acted differently based on our values.

3) Will we apply what we’ve learned to other challenges we face?

Given what we’ve learned about how a good health response is also good for the economy, what I really hope is that we apply this lesson to the other challenges we face. Because we face so many. Violence. Poverty. Inequality. The housing crisis. Antimicrobial resistance. Climate change. If you had asked me a year ago whether we would soon be closing our border and entering one of the strictest lockdowns any country has applied, I would have said no way! But a few weeks later, we did exactly that. We did something none of us would have ever imagined doing. And it shows we can take unbelievably drastic action to tackle a serious problem. We’ve shown we can be world leaders. So why stop with Covid-19?

2) Living through a pandemic isn’t what I thought it would be

Despite infectious diseases being my specialisation, I can’t say I’d spent much time thinking about what it would actually be like to live through a pandemic like this one. One of my favourite movies is Contagion, and it’s been interesting to watch it again and see what they got right and what they got wrong. Here in New Zealand, there was no looting or rubbish piling up in the streets. Instead, we had our big lockdown, with everyone but our essential workers staying home. We put teddy bears in our windows. Every day I went out for a bike ride. It was such a surreal experience without the usual traffic. I’d love our cities to be more like that in the future.

And speaking of essential workers, the pandemic has changed many people’s understanding of who an essential worker is. So many are on low wages, having to work multiple jobs to try to make ends meet. Knowing what we know now, how can we stand for this? I’m so grateful to the essential workers who have to work when we are asked to stay home. But they don’t need our gratitude. They should be paid a living wage and valued as the essential members of society they have always been.

1) The importance of communication

As a publicly funded scientist, I’ve long believed that my research doesn’t end with the publication of an article in a scientific journal. I’d even go so far as to say I feel morally obligated to engage with people beyond my scientific peers. I’ve taken that obligation seriously and have spent the last 10 years working on how to be a better communicator. In 2013 I was awarded both the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science Media Communication and the Royal Society Te Apārangi Callaghan Medal. A whole year before the pandemic I was made a member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to microbiology and science communication.

But many times over the last 10 years I’ve been close to giving it all up. Being a good science communicator isn’t how you get grant funding or a pay rise or promotion. In fact, I was told on more than one occasion that I couldn’t possibly be a serious scientist with all that working with artists and tweeting and blogging. In 2013, on a high after winning those awards and trying to secure a more permanent lecturing position, I was told I should count myself lucky that they were even considering giving me a job.

So it’s ironic that working with cartoonist Toby Morris has turned into the most productive and impactful collaboration of my career. As a scientist, I’ve always hoped I would be able to make a difference in the world. For the last five years, I’d thought that might be through the work my lab is doing trying to discover new antibiotics that kill antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

My collaboration with Toby has also shown me that I can really make a difference through communicating science too. Over the last year we’ve worked on over 40 graphics together. We’ve covered everything from masks, vaccines, and contact tracing, to genome sequence and viral variants and transmission. Our work has been seen by millions of people all around the world. It has been adapted and translated by governments and organisations and has even led to Toby and the Spinoff working with the World Health Organisation.

I’m glad I didn’t give up 10 years ago to fit someone else’s idea of what a scientist should be like. And I’m glad people are finally starting to realise how important communication is, especially when it comes to science. I’m just sad it took a pandemic.

Siouxsie and Toby’s collaboration, along with all our Covid-19 coverage, is funded by The Spinoff Members. To help us stay on top vital New Zealand stories, please support us here.