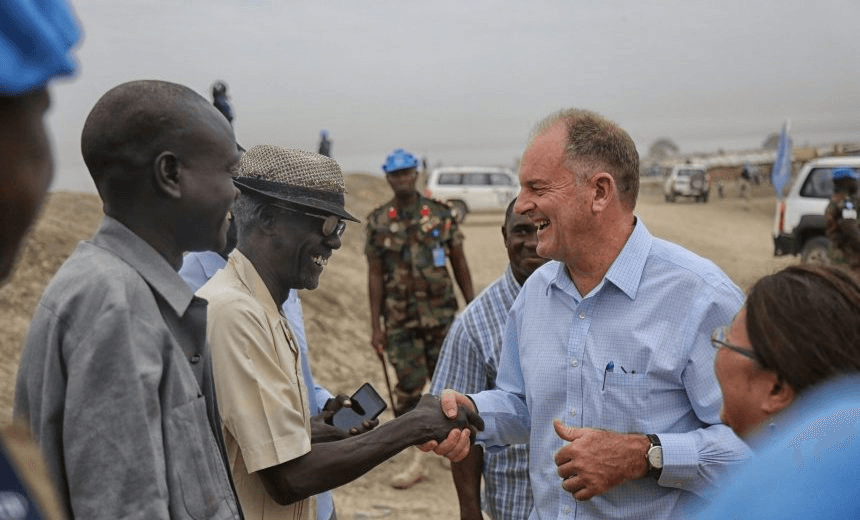

As the world’s youngest nation, South Sudan, celebrates its sixth birthday, the pursuit of a durable peace hangs in the balance, but there are glimmers of hope, writes New Zealander David Shearer, head of the UN mission

Just five days after Americans celebrate 241 years of independence, the people of South Sudan will today mark their sixth anniversary as the world’s newest nation.

Like the US, South Sudanese independence was born out of violent struggle. In contrast, any sense of citizenship was put aside as the country’s leaders went to war with each other just two years later.

A third of South Sudan’s 12 million people have fled their homes and almost two million live on the brink of famine. Inflation is running at 350% – the economy feels like a patient on life support.

Even without war, the obstacles the country faced when it won independence are immense. A country twice the size of New Zealand inherited just 200 kilometres of tarmac road. A simple 1,000 kilometre trip from the capital, Juba, to the northern-most town of Bentiu takes two and a half weeks during the dry season. In the rainy season that we are in the midst of now, it is impassable.

South Sudan is blessed with good rainfall, fertile soils, oil and mineral wealth. Yet realising that potential requires education, expertise and, above all, good government. Sadly, many of the elites that took control of the country after independence squirreled away millions to their own bank accounts.

This is a situation that no one wants to continue, particularly the US, which played the role of midwife in delivering the newly independent nation. At the time, it described how its “special relationship” with South Sudan brought with it “special responsibility” and, today, it continues to shoulder the biggest burden as the largest donor of humanitarian aid.

Political and media commentators wax ever more lyrical about the problems. But confronting them, and building that elusive peace, is much more difficult, particularly when confronted by those involved; many of whom believe that their successful war of independence offers the way forward – more conflict.

The United Nations is also no stranger to nurturing new nations. Liberia, Haiti and Côte d’Ivoire are countries now in peace that they are withdrawing from. But South Sudan is a particularly tragic case. The sheer scale of the obstacles make it one of the most difficult the UN has ever taken on.

The UN’s role in South Sudan is simple – to protect civilians and build durable peace. In reality it is far from simple.

There are glimmers of hope. A national dialogue has begun and may help pave the way forward for reconciliation among South Sudanese, as long as it engages genuinely with everyone. Meanwhile, the regional countries that surround land-locked South Sudan are re-engaging with both government and opposition groups to revitalise the peace agreement that was signed in 2015 but collapsed a year later.

The UN mission in South Sudan is also taking a fresh approach. It directly protects 220,000 internally displaced people who live inside or next to its bases across the country. Thousands of these people would not be alive today if it was not for peacekeepers drawn from 57 different countries.

New Zealanders make a strong contribution in South Sudan, working in humanitarian roles as well as with the UN Mission.

The Defence Force has three military liaison officers on the ground plus one based in my office.

But the New Zealand Defence Force could magnify its impact many-fold through positioning two or three trainers here. That simple presence could raise the capability of our 12,000 troops and make a real difference for our peacekeepers trying to do a difficult job in incredibly challenging conditions.

The UN mission has needed to step up its efforts. It is doing so with a new approach best described as proactive, nimble and robust.

Peacekeepers now patrol deeper into the country than ever before to reach far-flung communities. They now deploy rapidly in crisis situations, such as the helicoptering of 80 Rwandan peacekeepers to the village of Aburoc two months ago when fierce fighting forced humanitarian workers out, leaving tens of thousands of exhausted and frightened civilians facing an imminent outbreak of cholera. Just that intervention, together with humanitarian agencies, saved hundreds of lives.

Peacekeepers respond robustly when denied access to areas by armed actors and when they come under attack themselves. When Ghanaian troops came under fire in Leer, threatening the lives of 1,300 displaced people sheltering next to the base, they rapidly returned fire, deterring the attack.

But the UN is in South Sudan as peacekeepers, not war-makers shooting its way through situations as others often expect us to do. Getting the balance right – standing up for civilians yet staying neutral and out of the conflict – is tricky.

The UN is not alone in its endeavours. Hundreds of humanitarian workers risk their lives every day in atrocious conditions to reach people needing food and health care. They show tremendous courage and their efforts are working. The aid is getting through.

While the mood in South Sudan for their 9th of July celebrations may not be celebratory, we remain hopeful that in time the people will feel the same pride of being citizens of a country protecting their rights as in the US, New Zealand and so many countries around the world do. We take it for granted – they dream of doing the same.

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.