The Olympic women’s marathon was first held in 1984, largely thanks to one woman and her historic run 16 years earlier.

On February 7 1984, two men walked untethered in space for the first time. Six months later on Earth, women were allowed to run the marathon at the Olympic Games for the first time. In both instances, viewers questioned whether it was physically possible for the participants to complete the exercise.

One woman who knew better was marathon runner and commentator Kathrine Switzer. She watched as her fellow American Jean Benoit won comfortably in a time of 2:24:52. A time that would still be a top ten finish 30 years later. As each runner entered the stadium and was cheered on by the Los Angeles crowd, Switzer knew progress was being made. Finally everyone would know that women were not only capable of running marathons, they were capable of running them fast.

Twenty minutes later, all but eight of the 44 runners had crossed the line and Switzer’s broadcast was about to be cut. A massive success for women runners all over the world. Then Switzerland’s Gabriela Andersen-Schiess stumbled into the stadium.

Andersen-Schiess was never expected to win, or even place well, but she went into the historic race expecting to finish strong. Instead, with the smothering heat of Los Angeles in August and running straight by the last water station, Andersen-Schiess was fading fast. Her mind was clear and she knew she only had 300m to go, but her body wouldn’t listen. A medic rushed over to help but she waved him away, determined to finish at any cost.

Switzer watched as Andersen-Schiess staggered sideways, arms flailing, head bobbing, and nearly toppled off the track. She watched and wondered if as well as this being the first women’s marathon at the Olympic Games, it would also be the last.

Kathrine Switzer had run a lot of marathons since taking up long distance running at 18, while attending Syracuse University. “There were no women’s sports at all at this university,” she said, speaking from the 2018 New York Marathon expo, where she’s partnered with New Zealand menstrual cup company Hello Cup to support women distance runners, particularly those facing the unenviable task running a marathon while on their period.

“I went to the men’s cross country coach and asked if I could run on the team. He said no.” But he let Switzer train with the boys and soon she found herself running with veteran marathoner and volunteer coach Arnie Briggs. Briggs would regale Switzer with stories of his marathon races while they ran, which made her desperate to finish one, despite not running long distances at all. “The longest I’d ever run at that point – the autumn of 1966 – was three miles.”

Six months later in April of 1967, Switzer would become the first woman ever to register and complete the Boston Marathon.

“I did it because Arnie Briggs said he didn’t believe any woman could ever run a marathon,” she said. “He was absolutely convinced that women were too weak and too fragile, even though we were running together every night.” So Switzer ran with him, further and further, until two weeks before the race when they ran the full 42km and then some.

“When we were coming into the imaginary finish line he said ‘I can’t believe it, you look great.’ I said ‘I don’t think we measured this course right, let’s do another 10k’. So we did, and he passed out at the end of the workout.”

Switzer always knew she would finish the Boston Marathon. At 20 years old and having run 50k, she was even hoping to post a good time. Briggs, a recent convert to the idea that women could run more than a few miles at a time, would accompany her, no longer believing that she would spontaneously combust mid race. “Remember when you were studying in school, people used to say they’d be afraid that they’d fall off the edge of the Earth,” she said, in an attempt to explain his thinking. “Well Arnie was always convinced that some demon thing would happen and that I would collapse, I would fall off the edge of the Earth.”

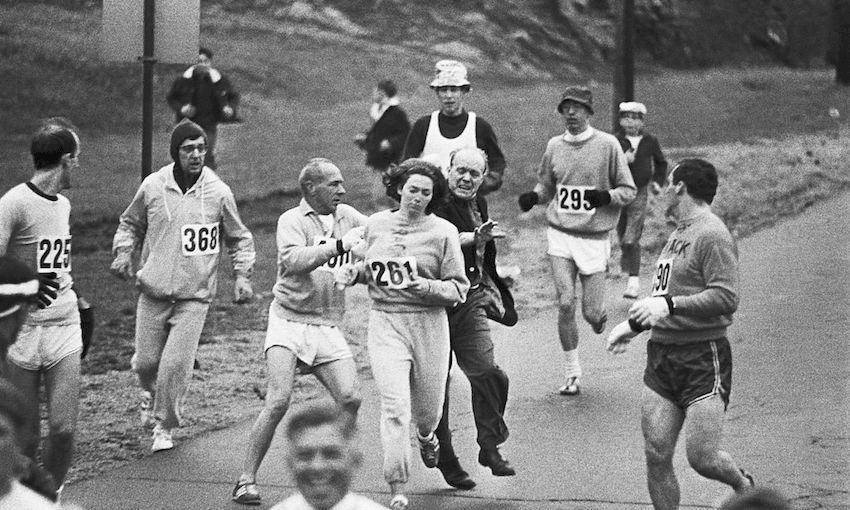

A demon did appear, in the form of Boston race organiser Jock Semple. Semple didn’t allow women to run in his race, but with registrations only requiring an initial, K. Switzer could’ve been any man. Switzer’s identity was revealed early in the race when a reporter in the press truck pointed her out to Semple. Outraged, Semple ran onto the road and tried to stop Switzer from running by pulling off her race number, 261. Switzer’s boyfriend at the time executed what can only be described as a textbook shoulder check, sending Semple flying. Switzer continued her run, flanked by her friends and coach, and finished with a time of four hours and twenty minutes, a full hour behind the first woman finisher Bobbi Riggs, who ran unregistered.

“I was paranoid because I thought the police were going to throw me out or something. So it was under difficult circumstances. The objective was simply to finish that first race.” The event was covered in national media, including the New York Times. “Kathy Switzer, despite her soft brown hair and winsome look, can be more than peaches and cream,” read the report.

It wasn’t until 1972 that women were allowed to officially register for the Boston Marathon, and Switzer placed second in 1975 with a career best run of 2:51:37. But despite that, and winning the 1974 New York Marathon, Switzer never considered herself an elite athlete. “I was more interested in the fact that we were denied opportunities and that somebody needed to make those changes happen,” she said.

“I knew that I had a voice and a substantial photograph [laughs] and that I was good enough to be taken seriously as a good athlete, so I had the credibility.” She used that platform to organise the first women-only long distance races, with cosmetics giant Avon acting as the major sponsor. After getting the races into 27 countries across five continents, Switzer had one last goal: to get the women’s marathon into the Olympics.

“I told Avon we could get the marathon into the Olympics, so we supported doctors who were very forward thinking about women’s ability and endurance and stamina. They gave us data that showed that something like the shot put or the 400m or the 100m were not ideal for women. But the ideal event would be the marathon because that’s what we naturally excel in.”

In 2017, Courtney Dauwalter won the MOAB 240 – a 240 mile ultra-running race where men and women compete together – beating the next finisher by more than ten hours. While men, for thousands of years, have had the raw strength and speed over women, it’s the women who have the stamina. As is becoming clearer, the ultra-running endurance races are one of few sporting areas where women and men can compete together.

Switzer and Avon’s public campaign worked, and in 1981, the women’s marathon was voted onto the 1984 Olympic programme. Switzer had accomplished her biggest feat, and was glad to be commentating, rather than running. “People were saying ‘I bet you’re sorry that you didn’t get to participate in the Olympic Games’ and I said ‘When you get the event in the Olympic Games, the real talent emerges from the woodwork.’” She was right. Switzer’s best time of 2 hours, 51 minutes would have placed her in the last five finishers. Instead, she watched from the commentary box as Gabriela Andersen-Schiess looked ready to collapse on the track in front of millions of viewers. “I was really worried that when the world saw that they would say ‘oh see, women aren’t capable’” But instead, the crowd roared and cheered Andersen-Schiess around the final bend and down the home straight, appreciating the heroic finish.

After the historic race, it was Switzer’s now-husband, New Zealand runner Roger Robinson, who summed up the impact of that race on young female athletes around the world. “Maybe the greatest thing of all is that this Olympic marathon allowed women to be exhausted in public.”

Last year Switzer ran the Boston Marathon again, aged 70. She registered and wore the same race number she wore 50 years earlier, 261. With 12,000 women running that day, nobody looked at her twice.