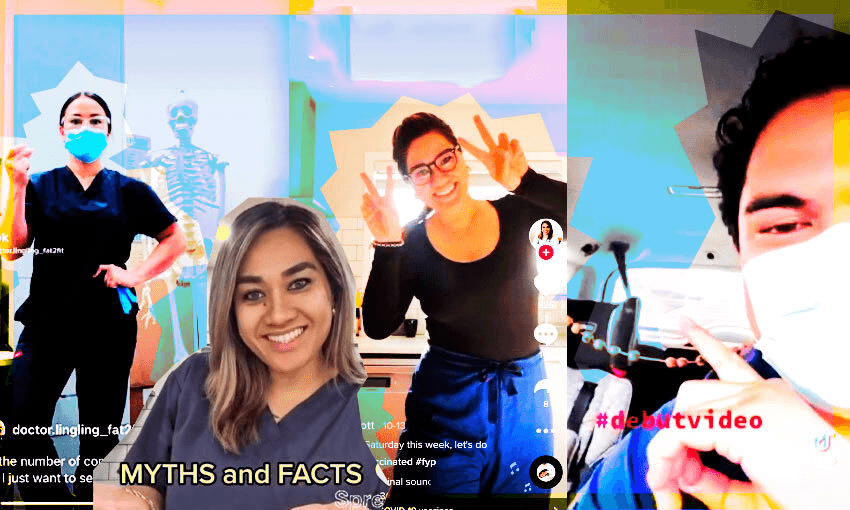

In an effort to get more Pacific people vaccinated, a group of doctors have taken to TikTok and Instagram to get the message out there.

Singing “vax-a-nation time come on” to the tune of ‘Celebration’ with a broom handle mic and her kitchen as a backdrop might not make Dr Vanisi Prescott TikTok-famous. But the way the Tongan doctor from Mt Roskill sees it, rejigging Kool and the Gang’s classic 80s hit could just be what a vaccine hesitant person needs to see. And Prescott is not the only Auckland medical professional employing these tactics. Prescott is part of a small group of young Pacific doctors utilising their social media savvy and meagre spare time to promote the Covid vaccine and debunk myths.

Prescott, who works at the Stoddard Road Medical Centre, Mt Roskill Grammar and Three Kings Accident & Medical clinic, says the long hours and lost time with her children will be worth it if she can help her community get protected against the worst effects of the virus.

“Lockdown has been pretty overwhelming,” the mother of three says. “Trying to educate our community and our youth, on top of work, has been pretty crazy and I’ve basically had to sacrifice family time to get the word out there and advocate [for people to get vaccinated].”

She says using TikTok was initially just a way of letting her hair down while doing some funny dances with her daughters, but it’s quickly become an important tool in her work encouraging those still feeling unsure about getting immunised.

“My daughter is 12 and she’s on TikTok quite a bit, so I was wanting to just get involved with what she was involved with,” she says. “Then all the misinformation started going around [about Covid] that I thought, wait a minute, this will be a good opportunity to actually reach out to those that aren’t listening to mainstream news or media.”

Prescott’s page, which has grown to over 24,000 followers in the last 18 months, not only features her hearty singing but also showcases her dance skills and answers to questions like “Does the mRNA vaccine change my DNA?”

View this post on Instagram

Alongside her full-time role as a Māngere GP, Dr Emma Chang-Wai has in recent months begun adding weekend stints at pop-up vaccination sites and check-ups with patients in MIQ. Like Prescott, she’s active on social media, but Instagram is her platform of choice. Chang-Wai has over 5,000 followers, and while she initially used her videos to inspire others with her own 30kg weight loss journey, she has also pivoted to Covid-related content. She says because there is such a “big mistrust in the system” she felt it was necessary to combat misinformation and be “visible in this space” as a local Pacific doctor.

Ōtara Family and Christian Health Centre’s Dr Va’aiga Autagavaia is relatively new to TikTok but between clinic shifts and parenting two children under three he has started to make videos about protecting yourself and your community from Covid-19. He made the decision to get active on social media after seeing a post accusing Pacific doctors of only doing vaccinations to protect their jobs.

He’s also spoken to a number of churches, workplaces and community groups via Zoom – events that he says “have been really good because it shows there’s a clear desire from communities wanting to know more and hear from doctors like us”.

“I’ve just been trying to promote open, respectful discussion about this stuff and I’ve been surprised by the number of people who respond positively.”

However it hasn’t all been positive. Prescott and Chang-Wai say their videos have also brought out social media’s ugly side.

“Initially I just got a lot of positive feedback but when I started posting about Covid and the vaccine I got overrun with so much hate and negativity,” Prescott says.

“I’ve had quite a lot of threats, like people saying they will come and get me if something goes wrong [with the vaccine] or that they will report me. But I’ve learned to just brush it off and just think about our people and that we need to get this message to as many people as we can.”

Chang-Wai says the negative feedback is one reason why most doctors aren’t doing similar things, but she feels as a Pacific doctor she has an extra obligation. “The easiest thing for me would be just to just live my life but it’s so hard for me to just sit back and say nothing. This is our protection and we have to reassure our people this is the right thing to do.”

All of which makes the affirming reactions that much more meaningful, Prescott says. “I’ve had people tell me, ‘if it wasn’t for you Pacific doctors speaking about this, I wouldn’t have got vaccinated’. We’re really putting ourselves out there, but seeing the wider good that can come out of it has been truly amazing.”

Given the extra stresses it places on their free time, do they resent the government for not rolling out more pro-vaccine messages catered to their Pacific community?

“I know there are people employed to do this sort of thing,” Chang-Wai says. “But I also think it’s important for these messages to come from our people who are actually working in these spaces.”

Autagavaia is less sanguine, noting that delays to the vaccine rollout to Pacific people has given more time for misinformation and conspiracy theories to take root.

“We aren’t doing this to get paid and even though we are doing it out of love and care for our patients, it probably should have been a formal campaign – not just now, but rolled out ages ago in a proactive way.”

Though he’s pleased to see Pacific vaccination rates creep towards 90%, Autagavaia is also concerned about the unintended consequences of mandating vaccinations for people in certain industries.

“When you’re being mandated and your livelihood is at stake of course you’re going to get it. But what I’m hearing from my patients, family and friends is that this has done a lot of damage to their trust in authorities. I don’t think that will heal anytime soon or once the pandemic is out of the way, which is really sad.”

But despite the mistrust and division that’s been sown over the last few months, the doctors know their public efforts will be worth it save more lives. They also want to encourage others to help share the same messages – even if that means doing some bad lip syncing in the process.