Isobel Ewing and her mate Georgia Merton rode their bikes through northern Pakistan for a month and made a film about it. This is (some of) their story.

It’s only when I catch my reflection in a shop window that I see why people have been staring.

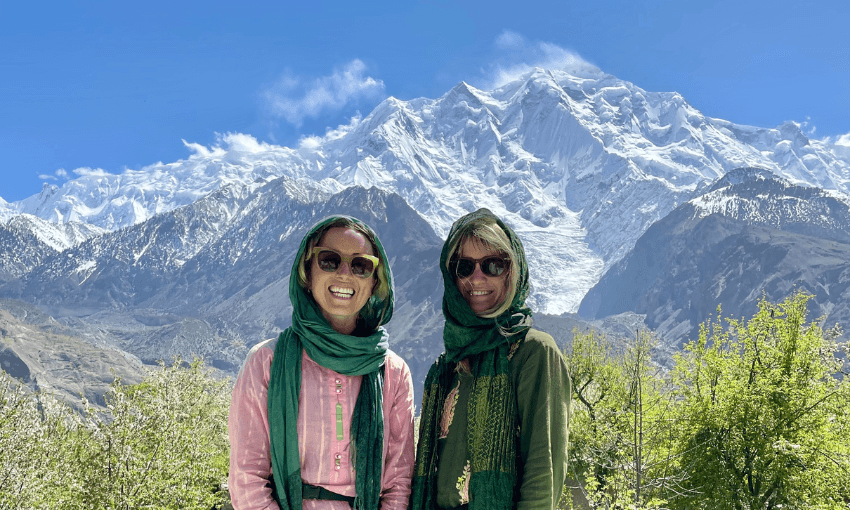

My Barbie-pink shalwar kameez, the long tunic and pants worn by men and women in Pakistan, is billowing behind me. It’s vibrantly complemented by the emerald green head scarf tucked under my helmet, but clashes with my big, yellow-framed sunglasses.

I’m also riding a gravel bike heavily laden with panniers, in a country where over three weeks of riding we barely saw women outside of a domestic setting, let alone riding a bicycle. In fact, one perplexed local man with the surprising name Jeff asked us: “Is it necessary to go everywhere by bicycle?”

I’m not new to bike touring, having extensively pedalled the back roads of enchanting countries from Tajikistan to Hungary. But I am new to cycling in full respectful garb in the middle of Ramadan, accompanied only by my good mate Georgia Merton.

So, what is it like to be two Pākehā women cycling alone through the backcountry of a devout Muslim country? Well, clearly our efforts at modesty did little to help us blend in. But as we soon discovered, the biggest risk to our safety was our tendency towards the cavalier (misjudging distances to the tune of 20km in a remote valley as snow began to fall) and a complete lack of mechanical knowledge (failing to recognise a crucial washer was missing from a rear wheel resulting in an almost catastrophic failure, saved only by a fortunate encounter with a bike mechanic in the town of Aliabad).

We’d landed in Lahore and taken an overnight, hair-raising bus trip to Gilgit, a town that’s a smudge of green in a broad, grey valley near the confluence of the Gilgit and Hunza rivers. The plan: to ride our bikes north on the Karakoram Highway, one of the world’s highest paved roads that snakes its way up to the border with China. And while we were at it, to shoot a film that’s soon to screen at the New Zealand Mountain Film Festival.

The shalwar kameez was suggested by our kind Lahore guesthouse host Hashaam, and we happily obliged, eager to be respectful of local custom. It was only after we hopped on our bikes that we discovered the loose, floaty clothing provided the added benefit of helping us feel feminine in the saddle, a sensation denied by squeezing one’s flesh into Lycra.

After some days on the road, we began to wonder if we unknowingly bought our shalwar kameez from the “novelty” or “fancy dress” section of the department store, as we did not see one woman clad in such a garish pink. Women wore mostly mute tones in their kameez and head scarves, which fell in step with their quiet presence in society in general.

Crowds of men would materialise when we bought vegetables, or stopped to inspect the map, and it would be only men who struck up friendly conversation. We found ourselves craving the company of other women, but when it did happen, we found the scraps of conversation we could manage with men were impossible with women, who never had the chance to practise their English, spending most of their time in the home.

One morning I was kneeling on the dusty roadside making a right scene of dealing with a flat tire, when a man passing by paused to have a chat. From his few English phrases, I was able to deduce an invitation to breakfast, and upon his direction we followed a small boy up a dirt track through cherry and apricot trees thick with blossom to a traditional mud-walled house.

It turned out the man wasn’t in fact present to host us, instead it was his wife who kindly invited us inside, her kind face betraying no displeasure at the sudden requirement to host two alien-looking strangers.

Warmed by the rudimentary wood stove inside, we sat cross-legged on piles of thick rugs adorned in faded floral and leaf patterns while she served us a spread of eggs, biscuits and fresh bread and butter alongside dried apricots, almonds and almond oil from the trees outside. Even in early April there’s a briskness to the air, and the locally-sourced foods remind us that during winter people here are forced to be entirely self-sufficient.

Soon, the couple’s son appears and sits down to eat with us, while his young wife helps her mother-in-law. Conditioned to Western norms, I ask how the couple met, and he replies good-naturedly that during his time at university in Karachi he “tried for two years to find a love marriage but did not succeed.” So he came home, and his father identified a suitable young woman in the village. They were wed soon after.

After breakfast the gentle couple helped us mend a puncture, him holding the tube steady as she carefully applied glue to a patch from my kits. In our month of cycling, it was one of countless small kindnesses bestowed on us. Another example was the many rides we were offered, our bikes slung in the trays of trucks or lashed to the roof.

On one occasion, two men picked us up as we hitch-hiked at the entrance of the “China Pakistan Friendship Tunnel”, a monumental piece of infrastructure vastly incongruous with its remote location, which was built after a landslide obliterated the highway and an entire village in 2010.

As we sped through the darkness, one of the pair suddenly demanded, “Are you afraid?” We falteringly replied that no… well, maybe we were a little bit afraid, then he interrupted.

“The whole world thinks we are terrorists. Do you think we are terrorists?”

In earnest unison we chorused that, no, not at all did we think them terrorists. His eyes fixed on me through the gloom. I was suddenly aware of how narrow-minded these stereotypes are, cast from far away on an entire nation of people, despite the people who believe and propagate those stereotypes often knowing little to nothing about that nation.

It was a remarkable moment that Georgia managed to capture on camera, and it forced us to confront our preconceptions while also exposing a frustration held by a local whose country’s reputation has been tarnished by extremist activity.

As women travelling on our own in Pakistan, some might say we should be a little bit afraid. But riding our bikes afforded us the slow pace that lent itself to interactions with locals, which were almost exclusively pleasant.

Jalal, a man with a roadside cafe who, upon hearing we would like chai and fries, hooned off in his car and returned 30 minutes later with a drum of water and a huge sack of potatoes. The truck drivers who hauled our bikes onto the sacks of fertiliser on the tray and gave us a ride when we realised we’d vastly miscalculated the distance to the nearest guest house in the remote Chapursan Valley.

Ali, our guest house host in the Chapursan Valley who reinstated the makeshift chimney and wood burner that had been packed away for spring for the benefit of two shivering New Zealanders. And the bike mechanic whose name we never learnt, who miraculously had the specific washer my broken bike needed and made several other repairs in under 10 minutes, then refused to accept payment.

We might have been completely out of place, despite our best efforts at dressing like local women, but Pakistan received us with a warmth that made us feel like welcome guests.

Although probably guests that you might have a chuckle about after they’ve left.

Inshallah screens at Session 6 – Pure NZ Rua in Wanaka on June 23 and Session Q2 Pure NZ in Queenstown on June 28. Tickets available here.