Anti-vaccine mandate protesters have now been outside parliament for more than a week. With parliament grounds closed indefinitely, and the weekend downpour turning the fields into sludge, what will become of the beloved government lawns?

It’s a verifiable urban oasis, with metres of luscious green grass stretching out in front of the curiously mismatched parliament buildings. Richard John Seddon, aka King Dick, stands guard, waving over his expansive domain. The pōhutukawa rustles its happy song in the brisk Wellington wind, and the pigeons coo their soft lullaby while risking their feathers to have a nip at the picnickers’ chips. Office workers loosen their ties at lunch and kick off too-tight oxford brogues. Forget the Garden of Eden; the parliament lawns could just be the closest thing to paradise in central Wellington.

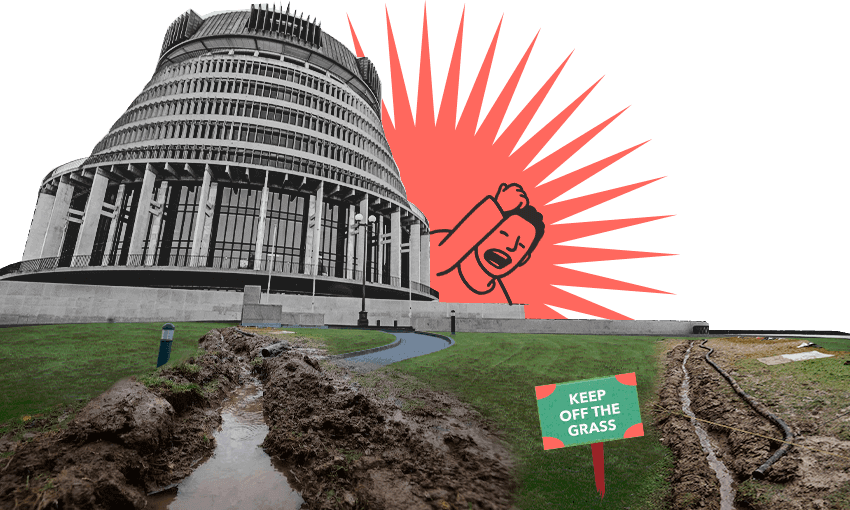

And now they’ve been destroyed. Anti-vaccine mandate protests are in their eighth day of occupying the parliament grounds, and they’re taking our sweet, sweet grass down with them. Tents have been up for days, sprinklers have been left on in an attempt to flush out the protesters, trenches have been dug, and extensive amounts of hay have been distributed over the new mud-scape that was the parliament lawns.

The parliament lawns aren’t just a nice spot to have your lunch. They’re a place of cultural and historical significance, having seen many protests before. From the Māori land march of 1975 to the Springbok protests of 1981 to the more recent school strikes for climate, the parliament grounds are no stranger to public dissent. But the lawns have never yet withstood a protest this size, for this long. It’s one that prime minister Jacinda Ardern has called “not any form of protest I’ve seen before”. In other words, the grass outside parliament has seen a lot of shit, but before now, none of it was literal.

Protests outside parliament can occur legally, and have occurred legally in the past. However, the current protesters are in clear breach of parliament’s rules, according to its website, mainly because they’re definitely fucking up the grass. OK, so there’s other ways in which the protest has breached the law, including trespassing, blocking the roads and harassment. But one of parliament’s first stipulations around protests on its grounds is that protesters must use walkways “to avoid damage to the lawns and flower beds”. Another clear condition is that “no structure, such as a tent, may be erected”. The whole web page gives “get off my lawn” old-man energy, and for the first time, I get it.

Tents destroy grass if left up too long. According to tentadvice.com – yes, that’s a real website, and no I don’t know how to put up a tent – tent stakes can destroy the root systems of grass. Additionally, sun not being able to reach the grass can kill it after a week, as the grass is cut off from, y’know, its main food source.

By turning the sprinklers on before the arrival of Cyclone Dovi, speaker of the house Trevor Mallard also contributed to the destruction of the parliament lawns. Accumulated water will drown grass roots.

Additionally, protesters have dug trenches to redirect the water from the sprinklers, claiming the lawn’s edges along the way.

But the last nail in the coffin for the parliament’s lawns is the hay that’s being spread over the protest grounds in an effort to keep the mud at bay. If the grass wasn’t suffocated before, this is the lawn equivalent of a pillow directly over the face. With this new blanket of hay, the parliament lawns have completed their transformation into a perverse parody of Rhythm and Vines – only without the drugs, and Celine Dion instead of drum and bass. Our only solace is that the smell of wet hay must be somewhat masking the smell of sewage.

Thus, our Garden of Eden, the paradise that is the parliament lawns, has been temporarily lost to us. A nation mourns. Although I can feel the eye-rolls through the abyss of the interweb void – stop being dramatic! It’s just a patch of grass! – let’s put all that lawn in perspective.

Last year, the total cost of maintaining and operating the parliament buildings was $33,151,000. Most of that is tied up in operating security and the parliament tours. This year, the budget that’s been set for those operational and maintenance costs sits at $29,209,000.

But after all the rubbish has been collected, the portaloos emptied, and the last straw of hay has been gathered out of the mud, the whole area will need to be cut off from public traffic, and the lawn repaired from scratch, said Jono, a lawn care expert at Lawn Pro Solutions.

The old grass structures will have been turned into mud, he said, so the top layer of the grass needs to be completely removed, and new pre-made turf laid down. That’ll involve a lot of heavy machinery and gear, which could get “quite complicated” in a high foot traffic area. There’s also the option of hydro-seeding to repair the grass, but according to Jono, “there’s no doubt about it. Given the high traffic [in the area], [and because] it’s gonna look like an eyesore in front of parliament, you’d definitely turf it.

“The average lawn [is around] 200 square metres, [which costs] upwards of 4.5 to 5k if done properly. So if you’ve got 500 square metres of grass there, [it’ll be] upwards of 20 to 25k,” said Jono. Looks like the government is going to have to reallocate some of that budget, and quickly.

“It’s not a cheap process, it would be pretty bloody expensive,” he added.

But there’s good news for all parliament lawn enthusiasts out there: the work can be done pretty quickly. In the late-summer heat and with the help of the irrigation system, the lawn would be “back in shape” within four to five weeks, he estimated, provided the area is completely cleared soon and the recovery process can begin.

This story has been corrected from an earlier version that said the cost of maintaining and operating the parliament buildings was $33,151. The correct figure is $33,151,000.