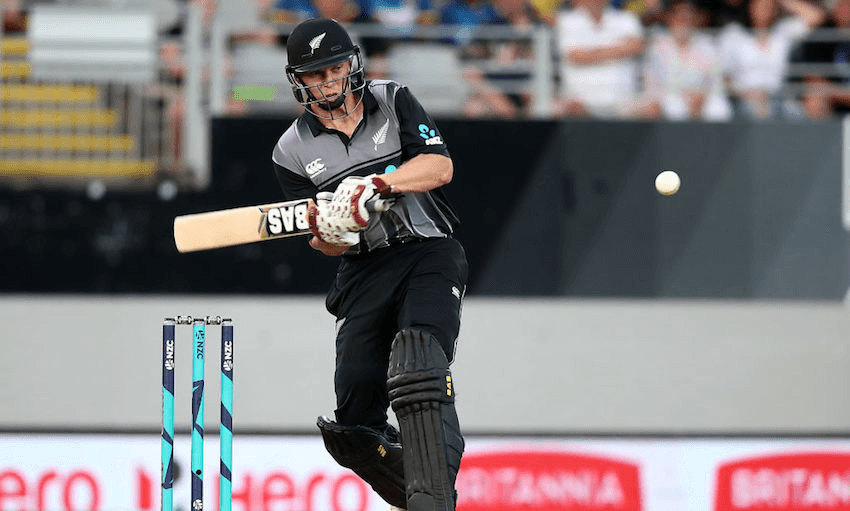

When cricketer Scott Kuggeleijn took to the pitch for the Black Caps last Friday there was no mention of his two trials for raping a woman in 2016, for which he was ultimately found not guilty. Asks Jessie Dennis, is silence really the best NZ Cricket can do?

Content warning: details of sexual violence.

On Friday evening I watched my first cricket game since I was a kid. It’s never been my thing, but I decided, after some holiday campground cricket forays, that I could get into it. After the rules were explained to me and I had the most basic of understanding, I even enjoyed it.

Among the players facing Sri Lanka on Friday was Scott Kuggeleijn. The name rang a bell, but I figured it must have just been from some sports news that I normally quickly tune out.

It wasn’t until Tuesday when I read this excellent blog by Nicola Gavey, a psychologist at the University of Auckland, that I realised why he sounded familiar. Kuggeleijn was put on trial for rape in 2016, and again in 2017 after the jury couldn’t reach a decision in the first trial. I looked around online to find what I thought would be the critical response to Kuggeleijn representing New Zealand on the world stage, but other than Gavey’s blog, there was nothing. Stone cold silence.

Kuggeleijn was found not guilty of the charges. There will be many who say that’s the end of the story. The justice system has spoken, and we should all just move on. Unfortunately, the story just isn’t that simple.

If we have any intention of reducing New Zealand’s horrific rates of sexual and domestic violence, we simply can’t watch on in silence as a man takes his place in our national team who, according to witness testimony, said ‘he’d been trying for a while and that he had finally cracked it’. He said this about sex with a woman who told the court she repeatedly said no and was crying and looking at the ceiling while he held down her arms. As the Crown Prosecutor said at the time, this woman had no reason to lie. Anyone who spends five minutes looking into the trauma involved in going through a rape trial as an accuser knows this.

If you’ve forgotten the details of the case or didn’t follow it at the time, Kuggeleijn did not deny having sex with the woman who accused him of rape. He argued that after repeatedly saying no to sex the night prior, she consented in the morning. The court heard that the woman had a panic attack in the morning when telling her flatmate about what happened, and that Kuggeleijn sent a text the next day apologising for “the harm mentally I have caused you”.

Kuggeleijn’s defence pulled out every victim blaming line and rape myth possible to discredit his accuser, well documented in this Spinoff article. I feel physically ill when revisiting these comments, about the accusers’ clothes, appearance, drinking and behaviour, and when thinking of what she went through during that trial, only to see him quickly reinstated to the team and be hailed as a future sporting hero. Kuggeleijn’s lawyer went so far as to say “Were you saying ‘no’ but not meaning ‘no’?” and suggested that her mention of being on the pill somehow meant she was consenting to sex.

Kuggeleijn’s lawyer said that “She couldn’t turn this man down yet again because she would then be thought of as a bitch or a tease.” Note here, that even Kuggeleijn’s own defence is not arguing she was enthusiastically consenting, but that she was reluctantly giving in to sex.

The judge in the second trial, in his ruling, said “Consent given reluctantly or later regretted is still consent.”

Well, no. Consent is enthusiastic and communicated.

It seems that Kuggeleijn’s defence rested on an outdated and incredibly damaging notion of what consent is and common rape myths. And it worked.

Even a few years on from that first trial, can we now agree, as a society, that what a woman was wearing and whether or not she said she was on the pill has zero bearing on whether or not she was raped? Can we now agree that saying no always, undoubtedly, means no?

So much has been achieved in recent years to draw attention to a culture in which women are subjected to gendered harassment, violence and aggressions on a daily basis. Incredible progress has been made in outlining how this culture is created and what behaviour builds and reinforces it. One of the most fundamental ways this culture persists is silence.

One could be forgiven for thinking that New Zealand Cricket simply hopes that enough time has passed that we might have forgotten the facts of this case and will therefore let Kuggeleijn’s joining the Black Caps go by without comment. For every survivor out there, not least of all the woman who went through these horrific trials, who saw Kuggeleijn on the pitch last Friday and felt minimised and hurt, silence simply isn’t good enough. What does this silence say to those women? What does this minimisation say to young boys about what kind of behaviour is acceptable?

No one is arguing that any man who ever commits any act of violence be forever shunned from society. But the alternative is not silence. New Zealand Cricket must step up and explain what makes them now confident that Kuggeleijn has significantly worked on his attitudes and behaviour towards women. If he hasn’t, he shouldn’t be in the team. And whether he is or isn’t, they should show the work they are doing to educate all their players on issues of consent.

We all know how much power sport, and cricket as one of our most popular games, holds in our society. NZ Cricket can choose to be a leader on reducing sexual violence in Aotearoa, or it can be part of the problem.

Jessie Dennis is Kaiwhakahaere/Manager of The Women’s Self Defence Network – Wāhine Toa.