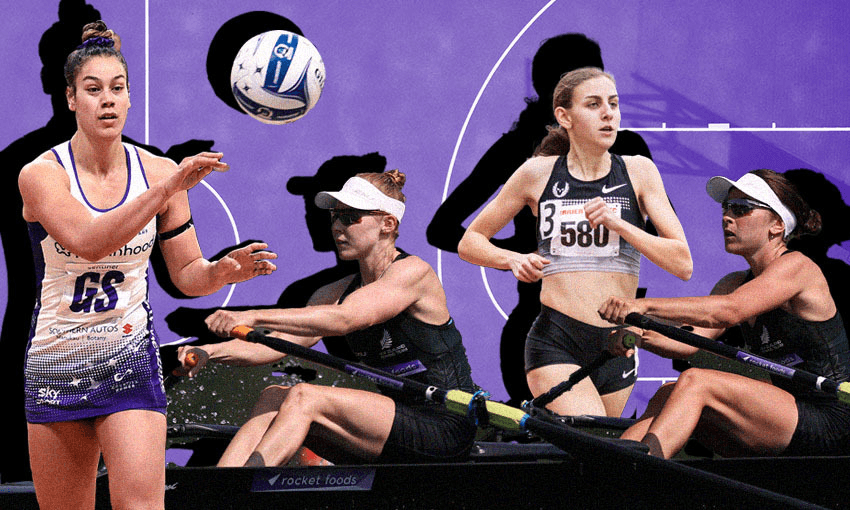

Elite sportswomen are expected to be faster, stronger, fitter, and leaner than ever before. But at what cost to their health? On the eve of the Tokyo Olympics, Venetia Sherson talks to experts about the risks to long-term health of women who will stop at nothing to be the best in the world in their sport.

This story discusses disordered eating and extreme weight loss – if these are issues you’ve been affected by please take care. A list of support resources are at the bottom of this page.

When New Zealand rower Zoe McBride stood on the podium at the World Rowing Championships at Ottensheim in Austria in 2019, she was on top of the world. She and lightweight double sculls partner Jackie Kiddle had just won gold, beating the second-placed Netherlands pair by more than four seconds, and smashing a world record on the way to the title. McBride appeared the picture of peak health.

What no one knew was she was starving herself. For more than a year, she had been eating fewer calories than a catwalk model. Her typical day began with a small bowl of oats, followed later by a small cup of cereal and perhaps a banana, to give the illusion she was refuelling between training sessions. Lunch was normally rice crackers with tuna; dinner a salad. She woke ravenous. She rarely went out to avoid facing food she dared not have. At the same time, her daily training schedule was rigorous, typical of an elite athlete preparing for world competition: four to five hours a day, including rowing at Lake Karapiro and weight and ERG sessions in the gym. Sundays should have been a day of rest, but she added running to her programme.

The rowing weight for lightweight women is less than 59kg. McBride’s weight was above that. She dreaded weigh-in days.

Just before the 2018 World Championships, she suffered a rib fracture – a sign of brittle bones, but not uncommon for rowers since all the power is directed from the legs to the arms through the ribcage. She rowed through the pain. Her periods became erratic.

After the world champs in Austria, she began counting the days until the Olympics, then scheduled for August 2020. “In February last year, I thought, it’s only five months to go. If I lose 250gm a week, I can still make weight.” She had done it before.

But on 24 March, New Zealand went into full lockdown; the following day the Olympics were postponed for a year. McBride, in isolation at her parents’ home in Dunedin, converted their garage into a gym and ran laps around her neighbourhood to maintain fitness. She suffered a stress fracture in the neck of her femur and, with no crutches available during the pandemic, sat at home and wept. “It was a really tough time. On the outside I kept up Zoom chats with my coach and other rowers, but inside I was really hurting.”

In desperation, she added another weapon to her arsenal. She began throwing up her food. Her menstrual period stopped.

When she returned to Cambridge, she was still above her target weight. “I felt overweight and unhappy with my body. Every waking moment was filled with anxiety and sadness. I was overwhelmed. But I still thought I could do it.

“I thought it will all be OK if I get to the Olympics and do well. I believed if I didn’t make it I would be a failure. I would do anything it takes to get there.”

But, in the end, not everything. After talking to her doctor and psychologist over several weeks, she realised the harm she would potentially do to her body long term outweighed her dream to win Olympic gold.

In March, she quit.

Her decision made headlines, but she is not the first elite sportswoman to speak out about the succeed-at-all-coats obsession with weight and training. This month, Silver Ferns goal shooter Maia Wilson wrote on Instagram about her determination to be the “skinniest version of myself” to ensure selection for the Ferns. “I created the narrative that the more weight I lost, the fitter I would be,” she wrote. “I started weighing myself six times a day.” Like McBride, she extended her training regime, doubling the number of conditioning sessions. She started feeling exhausted and her period stopped for four months. She was told to put on weight.

Katherine Black, an associate professor in the Department of Nutrition at Otago University, is in awe of the women who speak out about their experiences, which she says takes huge courage. Her research focuses on the health of female athletes and the risk of LEA (Low Energy Availability) when athletes aren’t eating enough to fuel their training loads, disrupting normal physiological functions such as metabolic and immune function, bone health and menstruation.

Results published this year from a survey by the WHISPA (Healthy Women in Sport) group, which reports to High Performance Sport New Zealand, showed half the female athletes had experienced changes to their menstrual cycles and nearly a quarter had had stress fractures. Fifteen percent reported eating disorders. Overall, nearly three quarters of the athletes believed sport was damaging their health.

The results reflect overseas studies. Some research suggests three quarters of sportswomen at this year’s Olympic Games may have ceased menstruation or be experiencing irregular periods as a result of low body fat, up from 30% two decades ago.

“Alarmingly,” says Black, “a large proportion of females possibly think they are doing the right thing by exercising and watching what they eat, when they are actually putting their health at risk. Some may know, but they don’t want to say anything which may jeopardise their chances of competing.”

For women, changes to menstrual cycles and amenorrhea, when periods stop completely, can be the first indication something is wrong – what some experts refer to as the canary in the coalmine. The female body cannot menstruate below a certain percentage of body fat. When periods stop due to low body fat, the body feels it is entering a state in which starvation is a threat. It begins to shut down all systems not deemed essential to life, including the reproductive system.

“Nature is very clever,” says Dr Stella Milsom, a reproductive endocrinologist with Fertility Associates in Auckland, whose research includes ovulatory disorders. “A lack of periods as a result of energy deficiency means that oestrogen levels are at rock bottom. They are likely to be that of a 60-year-old woman. And that can have significant long-term consequences for things like brain and bone health.”

And fertility. Without the correct signals, the ovary cannot stimulate follicles, produce oestrogen, nurture an egg, and release it into the fallopian tube for fertilisation. This can affect a woman’s ability to conceive even after she has stopped competing. Last year, top Australian netballers Natalie Medhurst and Geva Mentor shared their struggles with infertility, saying they hoped by speaking out that female athletes would consider their health as well as their sporting careers.

Milsom says many women think once they stop competing their cycles will return to normal. “This often is not the case if an energy deficiency state continues.” For teenagers competing at a high level, menstruation may not even begin, potentially leading to lifelong issues with bone density. “The key thing is that half our bone mass – the bone we are going to get to keep us strong and stop us fracturing – is accumulated in the years between your first menstrual period and around 20,” Milsom says. “Let’s say your first menstrual period is not until you are 17, and then it is very erratic; you’ve compromised that component of bone mass. For someone who might be going to row from age 13-30, you can’t catch up that lost ground. When periods stop, it is not just about the reproductive system. The whole body doesn’t work properly.”

She says while being relatively lean and training hard is clearly the goal, it should not be to the extent that a period stops. “If you are energy deficient, you are not matching energy in with energy out. When periods becomes irregular, it is an important cautionary sign.”

Katherine Black says many athletes are unaware or choose to ignore some of the warning signs. “People don’t talk about their menstrual cycle. It’s a bit of a taboo subject in many circles. To come out and say something is wrong, you’d have to have a large amount of trust. Historically, athletes have felt as long as they are meeting their goals, everything else is irrelevant. For some, not having a period is a badge of honour. It demonstrates they are training hard. But if you are unaware of the downstream consequences, you don’t know the damage that might be done. We were all young once. You feel like you are invincible.”

Zoe McBride says as a young rower she believed lack of periods was a sign she was working hard. “But by 2019, I knew it wasn’t healthy.”

Both Milsom and Black say social media puts further pressure on athletes to lose weight. In 2017, former Silver Fern Cathrine Tuivaiti went public about fat shaming. She told Stuff she always felt she didn’t live up to Kiwi expectations of how a Silver Fern should look. She said, “I am an elite athlete, but I was obviously bigger than everyone else… It is sad. We have all this pressure to look a certain way… But we don’t have to look like what people say. We don’t have to look like supermodels; we are athletes and we are allowed to have muscles and curves.”

One of New Zealand’s most successful triathletes, Andrea Hewitt, has also said triathletes always face pressure to lose weight so they are lighter on the course, which can result in eating disorders. “There is a general perception in triathlon that being skinny is related to being fast. But there are healthy ways to be skinny and it is all about balance.”

Overseas, elite US runner Mary Cain, at 17 the youngest track and field athlete to make a world championship team, made international headlines two years ago when she broke her silence to reveal how her former coach excessively pressured her to continue to lose weight, including taking diuretics. She suffered from amenorrhea and osteoporosis.

But Katherine Black believes attitudes are changing as a result of a greater awareness of the health consequences of LEA. “Athletes speaking out do wonders. People can relate to it. As hard as it is [for them], it really does help to raise awareness and increase knowledge.” Since the WHISPA research there have been changes to the protocols to work out who is at risk. She says researchers have to come up with intervention strategies, not just at the elite level but also at high schools and developmental level. “We want our young, female athletes to be healthy.”

Zoe McBride, meanwhile, is looking forward to a life beyond rowing. She has moved to Auckland with her partner, former world champion rower Ian Seymour, who missed out on a place in the men’s eight for these Olympics. McBride says while she has given away competitive rowing, she and Seymour will compete in the “Love Double” at the National Rowing Championships at Lake Karapiro next year. Crew members are defined as “a loving couple and a couple in love”.

“It will be fun.”

Where to get help

If you are suffering from an eating disorder, or if you suspect a loved one is, you should make a GP appointment as soon as possible.

- Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor

- Healthline: 0800 611 116. (Available 24 hours, 7 days a week and free to callers throughout New Zealand, including from a mobile phone)

- Eating Disorders Association of New Zealand: phone 0800 2 EDANZ / 0800 2 33269 or contact them via their website.

The NZ Mental Health Foundation has more information and advice on the causes, symptoms and treatment of eating disorders.