New research released by Good Shepherd New Zealand has exposed the country’s hidden economic abuse issue. The findings should be an important catalyst for action, writes Nicola Eccleton.

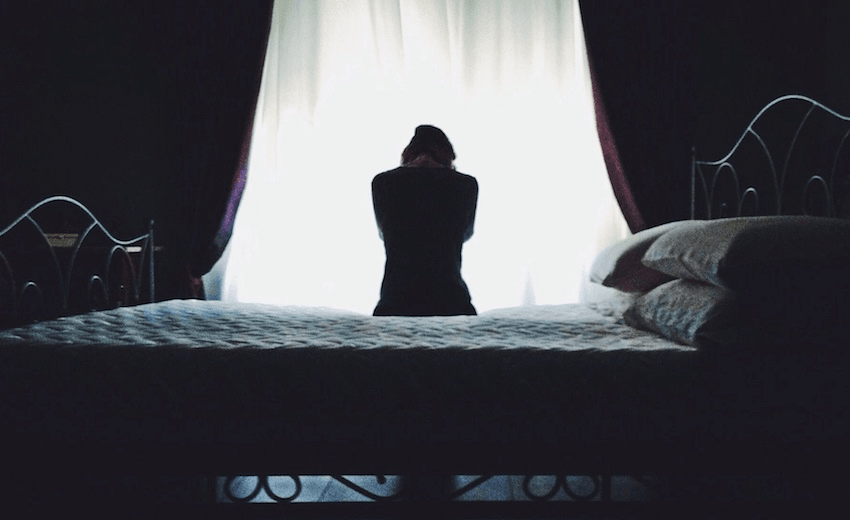

Economic abuse is a powerful, silent weapon used to control women – stripping them of their independence and trapping them in coercive relationships. There are no bruises, and no shouting heard through the walls to prove that it’s happening.

Good Shepherd New Zealand supports women and girls experiencing disadvantage. We recently undertook research to learn more about economic abuse as a form of intimate partner violence, specifically instances where men abuse women.

Our final report, ‘Economic Abuse in New Zealand: Towards an understanding and response’, was developed in consultation with more than 50 frontline workers and policy makers – including community groups, financial institutions, government agencies, legal support services, and women with first-hand experience of economic abuse.

Economic abuse is broader than financial abuse, which specifically limits access to money. Economic abuse restricts not only access to money, but also employment, education and other resources to limit independence or ability to improve circumstances. It is a pervasive and sinister form of control.

Examples include forcing women to provide food, clothes and care for the family with inadequate budgets, restricting her access to bank accounts and telling her what she is allowed to buy. Undermining a woman’s ability to earn money is common – men perpetrating abuse have reneged on childcare so she misses shifts, dictated her hours of work, and slashed the tyres on her car so she can’t get to her job.

These women are saddled with unmanageable debt and bad credit ratings as a direct result of their partner taking out loans in their name – referred to within the industry as sexually transmitted debts, or STDs.

Sadly, children are often used as leverage during and after the relationship. In many cases, men refuse to pay child support unless a protection order is lifted, or insist their partner ‘behaves nicely’ in order for the children to get Christmas presents.

The subsequent impacts are far-reaching, and often lead to long-term poverty. Women cannot access decent housing, have lost the confidence to hold down a job, and are not eating because they have spent all their money feeding their children.

Economic abuse is often cited as the single biggest reason women don’t leave physically and sexually violent relationships – they just don’t have the resources to leave. Many are choosing between homelessness and being in an abusive relationship.

During a discussion with a group of women affected by family violence, I suggested that women made decisions based on a hierarchy – the children’s safety, the woman’s safety, and can she afford to feed and house herself and the kids if she leaves. They quickly corrected me.

“No, Nicola. It goes the kids’ safety, how am I going to pay for it, then my safety.”

Whenever I talk to people about this work they ask me how widespread it is, and in the next breath tell me that what I have described has happened to their mother, sister or aunty. When I ask social workers how prevalent they think it is, there is never any hesitation in their response. “Oh, almost all family violence cases involve economic abuse.”

One of the reasons economic abuse is so difficult to identify is because it can be hidden within complex relationship dynamics. It is pretty common in New Zealand for partners to share bank accounts, a mortgage, and household income. But there are some real differences between sharing income and costs, joint decision-making about the budget and household priorities, and one person arbitrarily making all the decisions.

One of the most worrying findings was that while workers in family violence agencies are much better placed to identify economic abuse, they don’t actually know how to support people affected by it.

Women are of course not the only ones affected by economic abuse, but structural factors ensure they are significantly more vulnerable to it. Much of the domestic work undertaken by women is unpaid, and women are more likely to take time out of the workforce or take on casual or part time jobs in order to fit around their caring responsibilities. Women are also less financially secure across the course of their lifetime.

The current and previous governments have done significant work on family violence legislation. However, there are still no specific provisions for dealing with economic abuse in isolation – further contributing to the lack of awareness and understanding. An economic abuse lens needs to be put over existing policies and responses, and frontline workers need to be trained on how to respond and provide support.

But legislation is never a silver bullet. Sitting back and waiting for the government to fix our horrific family violence problem lets us all off the hook.

We need businesses and community organisations to invest in family violence training to upskill employees on recognising the warning signs. We need parents and schools to raise awareness of power and control in relationships, and the role of money. Banks, creditors and utilities providers need to have hardship policies that respond to economic abuse. As a community, we need to talk to each other and build peer networks so women experiencing abuse don’t feel isolated.

We also need to look at the factors that make women more vulnerable to economic and other types of abuse in the first place, and this means addressing the lack of financial security for women. We need to look at gender equity not just as a fairness issue but also as a safety issue.

As a nation flying the flag for female empowerment and gender equity, it is unacceptable that so many New Zealand women are reduced to poverty at the hands of their partners. Public concern needs to translate into public action.

Nicola Eccleton is Good Shepherd New Zealand’s Social Inclusion Manager. She has also worked at the front-line of family violence, supporting and advocating for men and women affected.