After 35 years of give-way eccentricity, amid predictions of chaos and catastrophe on the roads, Aotearoa reversed its law in 2012. Toby Manhire indicates carefully and takes a trip down memory lane.

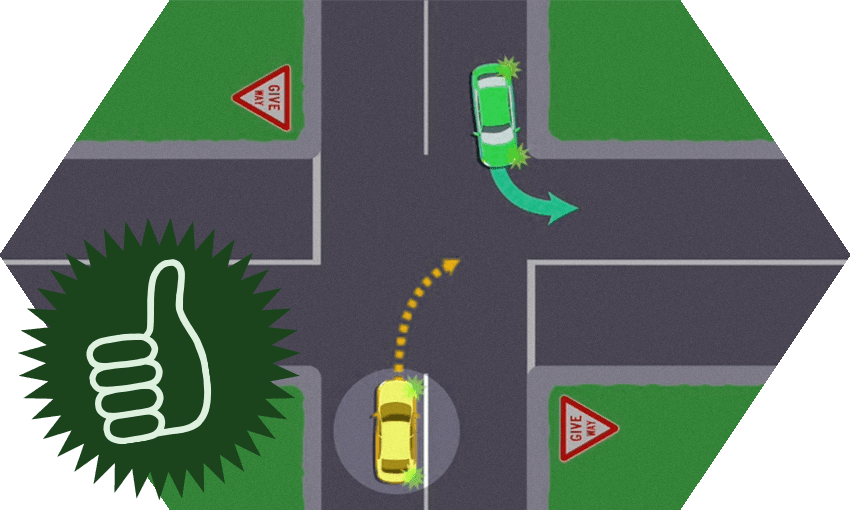

At 5am on Sunday March 25, 2012, something changed. Specifically, the New Zealand give way rule changed. From that point on, were you to find yourself nearing a left turn in your motor car, horse drawn carriage or bicycle as another driver set upon turning into that very same road approached from the other direction, well, you could just keep on going around that corner. New Zealand’s strange and unique 35-year-long experiment privileging the right-turning driver had come to an end. Across the country, people peeked nervously through their curtains at neigbourhood intersections.

“Chaos looms,” the New Zealand Herald had warned. “Get ready for confusion,” was the headline on a Herald on Sunday story foreseeing “motorists screwing up”. “Monday may descend into commuter chaos,” warned Stuff.

There were in fact two give way rules that changed that day: the turning-left-versus-right scenario and the rule for T-intersections, which before March 25, 2012, required a driver turning right from the horizontal bit of the T to give way to a driver right from the vertical bit onto the – look, it’s hard to explain. Watch the videos if you don’t know what I’m talking about.

Versions of those ads were the centrepiece of a $1.2 million TV campaign. Leaflets were delivered to 1.7 million homes. A poster advertising the change appeared on a Ferndale wall in Shortland Street. A Tui billboard got in on the act. “So now I give way to the right?” it read. “Nah, left.” Across talkback radio, social media and in appeals to parliament, however, the sound of resistance was heard.

“The give way rules should not change,” began Paul Marks, in a submission to the select committee considering the changes under the “Safer Journeys” policy programme. “There will be mass confusion by most drivers if it changed. It will cause thousands of accidents over the months while people would be getting used to the rule.” He pointed to an unscientific online poll that found 76% of respondents opposed change, and quoted someone called Alex who in response to the poll had remonstrated: “The argument that the existing rules are confusing is news to me because I have been driving for six years and I have never had any difficulty with the give way rules.”

A Facebook group called Don’t Change the NZ Give Way Rule, meanwhile, insisted that the rule wasn’t just fine as it was, it was a badge of national pride. “NZ is the only country in the world that has a Nuclear Free policy as well,” wrote the unnamed administrator of the page. “That is a very good policy, the best in the world I think. Our Give Way rule is also the best in the world but we want to change it because no one else has the rule. That is a stupid reason, we should embrace the rule and be proud because it is the best and be proud that we are different from the rest of the world!!”

In the comments, Sharon said: “Yeah NZ stick to your guns, don’t be like some places, sucking up to the rest of the world. I love NZ, don’t chuck it in.” A few minutes later, Sharon added: “One thing [that] does confuse me heaps is the roundabout near Welcome Bay in Tauranga. Freaks me out whenever I come over!!”

Dylan Thomsen started working for the AA in the months before the law change kicked in. “I was there,” he said, generously pausing for dramatic effect, “when it all happened.” It was, he recalled, “a huge deal at the time. The things that really stick out in my memory are that there was a lot of nervousness ahead of it and there were a lot of people expecting chaos and carnage on the roads.”

How did New Zealand end up with such an unusual give way rule, and what were the arguments to bin it? My search for some crunchy empirical evidence took me to a 2008 thesis by one AJ Wilkins, titled ‘Intersection Performance and the New Zealand Left Turn Rule’, completed for a master’s in engineering transportation at the University of Canterbury. Across 390 pages replete with sources and charts, the author had examined 10 intersections around Christchurch, modelling how they might be impacted by a change in the give way rule.

In a scene that might have come directly from the 2015 award-winning motion picture Spotlight, I found on the internet one Anna Wilkins, a consulting traffic engineer who shares her time between New Zealand and Australia. Could it be her? I fired off a message.

“Indeed that was my thesis,” came the reply, “and I reckon this email has approximately doubled the number of people who have ever looked at it.” I called her immediately. “At the time I’d just learned to do traffic modelling,” she said, explaining what attracted her to the subject, “so I thought that was quite exciting – not a view that was shared widely.” When a tranche of road changes were made in 2004, everyone from the AA to the Land Transport Safety Authority, as well as the minister and public sentiment were in favour of change, but the government decided against it. So the issue remained “kind of topical”, said Wilkins. “And all the other topics were pretty boring.”

In her thesis, Wilkins traced the history of “far side priority”, as the rule is technically known. It had been inherited in New Zealand in 1977 from Victoria, the Australian state famous for its love of culture, sport and blood-curdlingly idiosyncratic tram-inspired road rules. The introduction of the rule in New Zealand engendered in the late ’70s “public outcry, confusion, delay and annoyance”, Wilkins wrote. Victoria ditched it in 1993, a change which saw a 7% reduction in accidents. But New Zealanders kept on giving way to the driver turning right.

Across the 10 intersections, from major arterial route to smaller suburban areas, Wilkins found that “where there were volumes of traffic to make it a concern, the intersection had already been built to a level where that interaction wasn’t going to happen – it has been signalised, or had added lines”.

Her conclusion was clear: the rule should be flipped. It would be safer, it would be simpler, and any impact of efficiency would be negligible. Her research suggested that instead of wreaking havoc, “it would probably be just fine”. She found there would be some implications in terms of waiting times or intersections that needed tweaking, but “generally people would just get used to it … A lot of people are resistant to change and think we won’t cope. But people are just better at adapting than we give them credit for.”

Her research taught her another thing. “I remember at the time laughing and thinking: a lot of people don’t know the road rules now,” she said.

The minister of transport who made the decision to push ahead with change was Steven Joyce. Within the Safer Journeys reforms, he told The Spinoff, there were other changes that were more important – “the changing of the young driver age, the zero-alcohol for under-20s and those sorts of things”. But none excited the public mood quite like the give way rule. Together with demands for compulsory third-party insurance, it was “the issue that people randomly brought up the most”. Essentially: “A lot of people thought it was a silly rule.”

My research confirms this. Opponents of the rule change were outnumbered. A headline in the international pages of the Adelaide Advertiser newspaper, directly below a story about New Zealand’s Marmite shortage, called the existing rule “crazy”. One Marlborough driving instructor described the rule as “crazy”. A Waikato driving instructor, meanwhile, said the rule was “downright crazy”. On the Britishexpats.com forum, Matt said the rule was “absolutely crazy”.

Joyce thought so, too. “My favourite line about it was that it was one of those world leading things that New Zealand did that the rest of the world didn’t bother to follow … It just sort of sat there and confused everybody.” There was, however, some hesitation in cabinet. “It is fair to say that my colleagues were a bit nervous about it,” said Joyce. “They’d say, ‘Is it ‘worth it?’ Because, you know, you always spend a little bit of political capital on contentious things. ‘What happens if people get it wrong and smash into each other?’”

In September 2010, Joyce announced that the change would go ahead. It was timed for March 2012, to avoid getting tangled up in the 2011 World Cup or the election campaign. “Our current give way rules for turning vehicles are confusing and out of step with the rest of the world,” said Joyce at the time. “Research shows changing the rules could reduce relevant intersection crashes by 7%.”

As it happened, the post-election reshuffle meant Joyce was in a different cabinet chair come March 2012. “Gerry [Brownlee] had transport when it came into effect. I don’t think it was the thing he was most enthusiastic about inheriting – just in case it went wrong, right?”

How, then, did it all go in March 2012? Did the prophecies of doom bear out? According to the earliest reports, yes they did. “Just took the cat to the vet and can report that no one is following the new rules. It’s chaos out there people!” wrote Holly Walker, then a member of parliament, on Facebook. Her report was so early, however, the rule hadn’t yet changed. Distracted, perhaps, by the situation with the cat, she had been driving the streets of the Hutt Valley on Saturday.

Come the next day, there was no chaos to be found. “People were just like ducks to water,” Joyce said. “I remember driving around the first few days and just marvelling at how much people were following the new rule. And then I realised a fair number of them were probably following the new rule before it was the new rule. Some had never actually taken on the old rule. So perhaps in hindsight it wasn’t quite as difficult as it looked. The old rule had been set up in a way that was not instinctive for people.”

There was no chaos beeping the radar for AA’s Dylan Thomsen, either. “It all ended up being rather smooth and uneventful,” he said. “The change happened. People adjusted. There was a period of time where, rather than there being carnage on the road, people were extra-cautious.” Soon that hesitation had dissipated, too. “People navigated it all, and within a few weeks or months life was just carrying on with a different give way rule. No harm had been done.”

These days, he suggested, it would be a different challenge to communicate such a change. “One of the things that really stands out to me looking back on it is how much the New Zealand culture has changed. I remember when this change was coming in and being promoted. I remember both the 6pm news bulletins doing big stories on it, and both the 7pm current affairs shows,” he said. “It was a time when it was a lot easier to reach most people in the country with information and messages in just a few places. If you were doing the same thing today, I think it would be much more challenging, given all the different ways that people get their information.”

What did the official analysis find? To answer that, we turn, very naturally, to Simon Bridges and Jami-Lee Ross. Some years before Ross drove through the night from Auckland to Wellington and attempted, metaphorically but furiously, to run Bridges off the road, the then 27-year-old newbie National MP for Botany had the duty of putting a patsy question to the then associate minister for transport.

“What reports has he received on the public’s understanding of the new give way rules?” asked Ross from the back bench at the end of June 2012. “I am informed,” said Bridges, “that Kiwis are giving way like never before. We are a little over three months into the change, and I want to give credit to Kiwi drivers for the smooth switch-over to the new give-way rules. In April the New Zealand Transport Agency commissioned a survey of a thousand drivers. It shows high levels of awareness and understanding of the rule changes: 90% of respondents chose the correct option when asked which vehicles give way at an uncontrolled T-intersection, compared with just 61% surveyed in February. For the right-hand turn rule, 89% answered correctly, compared with 74% in the earlier survey.”

Returning with a supplementary patsy, Ross again: “Are there any other indicators that show that drivers are adjusting well to the changes?” Bridges: “To date there have been no serious incidents attributable to the changes. AA Insurance has reported only a handful of claims for minor crashes. There were a few very vocal critics who predicted widespread chaos and argued Kiwis would not be able to cope with the changes. These naysayers have been proved wrong.”

Asked for data on the impact of the change, Waka Kotahi provided the chart below, which shows a decline in deaths or serious injuries at intersection crashes of around 15% from the start of 2012 to the start of 2013, and a fall in the proportion of serious traffic accidents that took place at intersections. Whether the give way change is to thank for that is another question, and recent years suggest there is plenty of work still to do at the places roads meet.

I wanted to find out how the give way U-turn impacted ordinary people, but my deadline was closing in, so instead I asked my colleagues. Eli said it changed her life. Actually what she said was: “It changed my driving life in NZ.” Having migrated from the US, she said: “Only until this change did I feel comfortable driving the mean streets of Auckland. Before that I’d just call shotgun.”

Another colleague helpfully added: “The old rule was a leveller and gave the car turning right a chance. Now the car turning left has everything on its side.” And another: “Turning left is the honourable choice.” Yet another, whom I shall not name, seemed genuinely surprised to learn that the rule had changed at all. Another still, whom I have reported to authorities, said: “I still don’t understand the new one. I just vibe it, usually presume I should be the one giving way until someone toots me.”

Does Steven Joyce afford himself a small smile as he indicates left and takes the right of way, thinking I did this? “Ah, no,” is the answer. “There’s a whole lot of things that I probably get more excited about,” he said, offering examples such as the ultra-fast broadband, the Waikato expressway and electrification of Auckland railways. “But every now and then, I’m sure like a lot of people, I approach an intersection and get a sudden urge to give way to the drivers turning right across in front of me. And you remind yourself: no, the rule is actually very straightforward now.”

I sent a message to the Don’t Change the NZ Give Way Rule Facebook group. It was a longshot; it had been 10 years since the change and 10 years since anything was posted on the page. The next morning, my eyes lit up like a left-turning indicator. There was a reply. “Wow has it been 10 years already! Thanks for letting me know, I appreciate it,” said Don’t Change the NZ Give Way Rule Facebook, with a love-heart emoji.

What, I’d asked, did they think of the change all these years on? On the broader point, they were not for turning. “I still don’t see why NZ had to change its road rules just because most other countries have a different give way rule.” But also, they said this: “Well, it hasn’t been horrific having a new give way rule, that’s for sure. In the end it just seems pretty much the same as it was before.”

If there must be a moral to the story, let’s go with this, from Wilkins. “You look at how people react to one parking space being taken off the road or a bike lane [being added] – you’d think the apocalypse is going to come,” she said. “If you just snuck out and did it overnight people would probably adapt to it. We just get used to it and move on.”