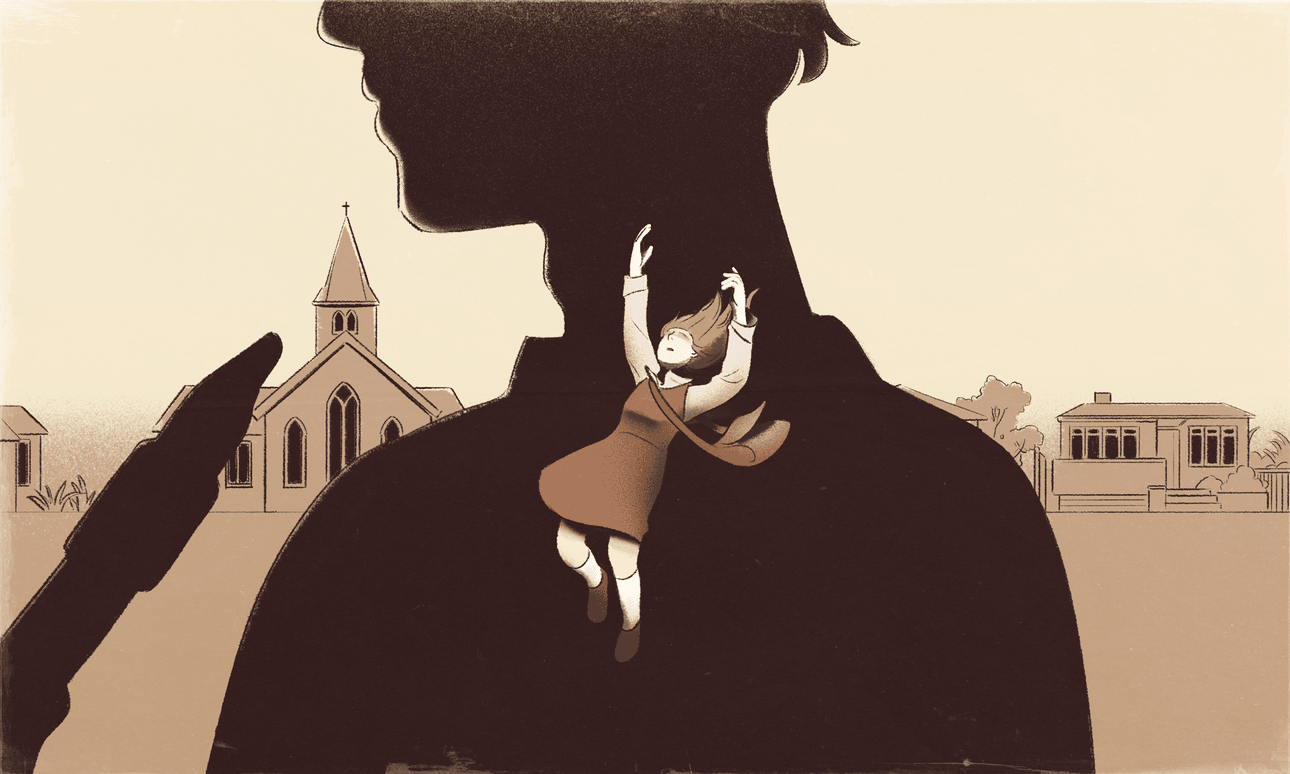

In April, The Spinoff published an investigation into music teacher David Adlam’s relationship with his 16-year-old student in 2004. Today, another former student of his from more than three decades earlier shares her own traumatic experience.

Content warning: This feature contains distressing descriptions of a sexual and emotional nature, along with their mental health implications. Please take care.

This story was made possible thanks to the generosity of The Spinoff Members.

Sarah* had only read one paragraph of When the lessons end when her stomach dropped. The story, published on The Spinoff in April, detailed the traumatic experience of Eva*, who was 16 years old when she had a sexual relationship with her clarinet teacher in his 50s. Her account included allegations of manipulation and non-consensual sex, the impact of which continue throughout her personal life and music career.

Sarah scrolled down until she found the only name she needed to see: David Adlam. “I thought to myself ‘that’s it’,” she says matter-of-factly, perched on the tidy grey couch of her Hamilton home. “I am going to stand up and speak now.”

What she proceeds to share is her own harrowing experience as a teenager with Adlam in 1973 – more than 30 years before Eva’s story took place – including allegations of non-consensual sex, a traumatic abortion procedure and a social climate that looked the other way. Although she had never before told the full story to anyone, it was Eva’s bravery in speaking up that inspired the retired medical practitioner, now in her 60s, to share her experience publicly for the very first time.

“Eva can just sit back now and think ‘I’ve started it, something is happening’… She can feel as though she has done all she can, which is something that I have never felt.”

Sarah grew up the eldest of four children in a deeply religious home in Hamilton – her mother had taught Sunday school and Sarah attended every week from the age of four. “My life really revolved around family, friends, school and church,” she laughs. “I didn’t really do anything else.” She was a studious young woman who participated in athletics, Christian youth group and Girl Guides, and didn’t care much for teenage hijinks. “I always loved school. I hated school holidays because I would be bored out of my brains.”

Hamilton in the 1970s was less of a city and more of a large town. Everything died at five o’clock at night, except on a Friday when things died at about 8.30. There was one cafe called Pigeons up in Thackeray Street, and there was one nightclub that Sarah never went to. She wasn’t the nightclubbing type, her biggest display of teenage rebellion was sneaking into the more “charismatic” Assembly of God Church – her family was Anglican – and getting re-baptised when she was 15.

Her musical tastes were equally chaste compared to her peers. Sarah didn’t care for the Bay City Rollers, or Led Zeppelin. There were no boy band posters on her wall. “I didn’t really like popular music at all, to be honest, I just liked classical music.”

Sarah had wanted to play the piano from a very young age, but her family’s financial situation meant this was not possible. Her music education began at Fairfield Intermediate School when she was 11 years old, where she learned the descant recorder every Saturday morning. The classes were free, a necessity at the time. “We were not a wealthy family, so things had to be cost-effective.” After a few years, another instrument caught her attention while she was idly listening to National Radio. “I heard this wind instrument and I just thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard in my entire life,” she recalls.

At her next Saturday morning lesson, she told her teacher about what she had heard. He handed her a clarinet.

The instrument entered Sarah’s life at a destabilising time. Her parents separated in 1971 and quickly divorced, which was not the norm in the early 1970s. Her father stopped living at home and her mother married a prominent local businessman, regularly attending social engagements at night and leaving Sarah and her brother to look after their younger siblings. While she juggled the stressful demands of her family life, clarinet provided a soothing escape. She would frequently skip her double geography class to spend three hours practising.

“I heard this wind instrument and I just thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard in my entire life.”

It was through clarinet that 16-year-old Sarah was introduced to David Adlam. He started teaching clarinet at the Saturday morning music class in 1973, the year he turned 19, and Sarah remembers being immediately dazzled. “He was a fantastic teacher, he was a great musician and he was very charming and had a good sense of humour,” she recalls. “Some people just sort of move slowly and everything happens slowly, but with David there was always zest and energy there. He was a very attractive person.”

With Adlam as her Saturday morning tutor, Sarah’s clarinet playing quickly began to improve. Even nearly 50 years later, she remains complimentary of his musical talent. “He’s a very good clarinettist, he understood the instrument and how to get the best out of it – more than any other teacher I had,” she says. “There’s a lot more to music than just getting notes together, you’ve got to put the emotion and the understanding into what you’re playing, and he could do that too. He really was very, very gifted.” She had three other clarinet teachers prior to him, but says that “nobody was like David”.

Soon, Sarah was too good for the rest of the Saturday morning class, so began private lessons with Adlam at his parents’ home. She was still 16 years old. “I was getting his undivided attention for an extended period of time and he was an extremely good teacher. So I thrived,” she recalls. “I thrived.” As her playing strengthened, so too did her feelings. “I fancied him, you know? He was older than me, and he began to take me places to see some of his acquaintances and it just developed from there.”

She remembers continuing to be astonished by his musical talents, which he would occasionally rely on as a party trick. “We’d be in a social situation and people would say ‘David, play something in the style of Mozart’ and he would compose something that sounded just like Mozart on the piano, then and there,” she recalls. Despite his talents, her family had reservations – there was still the age gap and the fact that he was her teacher. But he visited their home and “was very charming to them”, and Sarah says their concerns soon dissipated.

“He came from a very nice family, his parents were lovely people, I don’t think anybody really suspected what he was really like.”

Being raised in the church, Sarah’s experience with boys at the time was very limited. She chuckles as she recalls kissing her best friend Roy at the age of six – “grossly overrated” – and going to the movies with Philip when she was 12 – “not interested”. At a Christian youth event at age 14, she held hands with a boy on the bus home, and that was the extent of her relationship history. The idea of having sex before marriage was not even on Sarah’s radar at 16. “Oh, that was a big no-no,” she explains. “It’s in the Bible and it’s very, very clear: absolutely not.”

Late one night in August, 1973, Sarah’s life changed forever. She was in the lounge of her family home with Adlam, after they had been rehearsing together in the orchestra pit for an amateur production of My Fair Lady. Her mother and stepfather were sleeping in the room next door and her siblings were sleeping down the hall. She and Adlam began quietly “making out” on the sofa, she says. “There was no expectation of it ever going any further, especially on my part, and no discussion about it.”

They were both fully clothed, and she recalls being shocked to realise that he had pulled down his shorts and underwear to expose his erect penis. She was wearing a skirt, and says he quickly pulled her underwear to the side and shifted himself on top of her. That is when she remembers starting to feel very concerned. “I remember trying to actually move him off me and trying to say ‘stop’ but I felt suffocated, absolutely suffocated because the weight of his body was on me and he was kissing me and I couldn’t do anything except mumble.”

Adlam then forced his penis inside the entrance to her vagina. She recalls a sharp pain as he thrusted and ejaculated inside her. Although it was over quickly, she says she still remembers it as if it were happening in slow motion. “There was absolutely no consent,” Sarah recalls. “I was shocked and I didn’t even fully comprehend what had happened. I was a total innocent, a virgin, I’d not had any sexual experience at all.” Adlam pulled up his pants and promptly left in his car.

In an email to The Spinoff, Adlam denied allegations of non-consensual sex with Sarah at her parents’ house in 1973, saying there was “little accuracy” in her recollection of events and said their relationship was “entirely consensual”.

Nearly 50 years on, Sarah’s voice still wavers as she recalls her feelings in the immediate aftermath of that evening. After Adlam had left, she remembers sitting on the edge of the bath in the darkness of her family bathroom, stunned.“There was a lot of self-blame and just sheer ignorance and disbelief about what had happened – did he mean to do it? Was this intentional? Was this just an accident on his part?” She blinks away tears from her eyes. “I sort of thought I should have been able to stop him – how could I have let somebody do this to me?”

In the days that followed, Sarah’s feeling of devastation started building exponentially, threatening to become “completely overwhelming” for the teenager. “That was when I thought ‘oh no, I have to shut this down, I can’t think about this now’.” Clapping her hands firmly together in front of her face as if slamming a book shut, she explains the emotional pain became too much to endure. “I blocked out the feelings associated with the event and I put a very firm barrier around them.”

For the next few weeks, Sarah says that she tried her best to carry on with regular life. She continued to have lessons with Adlam, even sharing the orchestra pit with him during a local production run of My Fair Lady. “I was still having contact with him despite what had happened,” she explains. “I thought to myself ‘I will think about this one day, at some stage, when it is safe for me to do so’.”

“I sort of thought I should have been able to stop him – how could I have let somebody do this to me?”

Over a month later, the vomiting started. “I had morning sickness, but of course I didn’t realise what it was.” She hadn’t told a soul about what had happened that night, convinced that the best way forward was to “stomp down” the memory. Her mother took her to their family GP in an attempt to figure out why she couldn’t stop vomiting. “Our family GP knew me well and it would have never occurred to him that I was pregnant,” she explains. After getting a second opinion, the GP instructed Sarah to take a pregnancy test.

In 1973, gaining a pregnancy diagnosis was not that simple. Home pregnancy tests weren’t available in Aotearoa until the early 1980s, which meant the only option was to provide a urine sample that would be sent to a laboratory for processing that would take at least several days.

When the results came back and Sarah was told she was pregnant, whatever was left of her past self completely shut down. “I had blocked off a tiny bit of myself after that first episode, and then the rest of it after that, completely.” Her mother was “very angry” and “disgusted” by the news. “My mother was very sensitive to social opinion, so it was just the most appalling conflict for her,” she says. “There was her Christianity, there was the social disgrace, and the appalling cost to my life of being pregnant and unmarried.”

The social and political climate at the time was not favourable towards young, unmarried pregnant women, and women’s reproductive rights were severely limited. Although the contraceptive pill had become available in Aotearoa 1961, a fear that it would fuel extra-marital affairs meant that single women weren’t able to access it until 1973. As the second wave of feminism gained momentum, so too did attitudes towards a women’s right to choose. According to Te Ara, the number of abortions increased from fewer than 70 in 1965 to over 300 by 1970.

Still, access to abortion care remained extremely restricted. A 1961 amendment to the Crimes Act made abortion legal, but only if it was performed “in good faith for the preservation of the life of the mother”. Opposition to abortion remained widespread across the country in the 60s and 1970s, led by The Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC). Largely funded by the Catholic Church, members included Ruth Kirk, wife of then prime minister Norman Kirk.

It wasn’t until 1974 that New Zealand’s first abortion clinic opened, a move met with strong opposition including court action, police raids and $100,000 worth of damage to the centre. Three years later in 1977, the Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion Act made abortion access slightly easier, although it still required authorisation by two consultants, and had to be deemed “‘clinically appropriate” in terms of physical and mental health after 20 weeks. It was not until 2020, 43 years later, that abortion was removed from the Crimes Act.

This meant that in 1973, Sarah had two options – either she would seek a termination, or she would be sent to one of the seven Bethany homes in Aotearoa. First established by the Salvation Army as a private maternity hospital for single mothers in 1897, Bethany homes were said to provide support during the 60s and 70s without the judgement or religious expectation that was often associated with single, unwed mothers.

Hushed conversations were had about what should happen to the pregnancy, but Sarah was never a part of them. “I was a bystander at the mercy of whatever was going on around me,” she says. “I just sat there and I existed and I didn’t let myself think and I didn’t let myself feel because it was all just too big and too dangerous for my mental health.” In hindsight, Sarah is grateful that her subconscious protected her. “This is what people do in times of horrendous trauma… So you can survive it, you just shut down.”

Sarah’s mother banned Adlam from visiting the house after the news of the pregnancy, but she never asked about the circumstances under which her daughter became pregnant. “She never wanted to know, she never, ever talked to me about it,” says Sarah. Her mother died in 2021.

Adlam confirmed to The Spinoff that he was the sexual partner involved in the pregnancy, but maintained that it was not a result of penetrative sex. “Both of us were extremely shocked, because at that stage we had not had sex and didn’t think pregnancy was a possibility. It was the one saving grace with both our sets of parents, as we were able to say honestly that we had not had sex, though I had climaxed (once?) while outside her vagina – hence the pregnancy.”

After a meeting between Adlam’s parents and Sarah’s mother and stepfather, it was arranged that Sarah would have a termination at Waikato Hospital. She remembers visiting a psychiatrist for assessment, and wondering how he would know she was mentally unwell – an essential criteria for approval of pregnancy termination – given her complete lack of emotion at the time. “I didn’t cry, didn’t appear distressed, I was just frozen,” she says. “But he picked it up, so obviously he was quite good at his job and maybe he realised what had actually occurred.”

Having now worked for more than 40 years in medicine, Sarah can diagnose her younger self in an instant: “I disassociated. I would have diagnosed myself as being extremely traumatised.”

After the psychiatrist she saw a gynaecologist who carried out the abortion at Waikato Hospital in late 1973. He was a well-known Catholic in the community, and Sarah sensed immediately that he was agitated about performing a procedure against his religious convictions. “He was extremely abrupt, extremely offhanded and was actually quite barbaric when he examined me,” she recalls. “He caused a huge amount of pain to the point where I was actually screaming, and then he told me off for screaming because I disturbed the other ladies in the waiting room.”

The procedure itself was brutal. “I’m convinced that he was a very angry man having to perform this abortion, or dilation and curettage as it was called then, against his strict religious beliefs,” Sarah recalls. “I bled horrendously, I was bedridden for over a week and was passing phenomenal great lumps of clots and endometrial tissue.” When her mother called their local GP, she was told it was normal. “I know from my professional experience as a medical practitioner that what I experienced was not at all normal.”

Sarah says she was clearly “very, very anaemic” from the bleeding, and her sporting success would be impacted for at least six months. When asked how she felt during that time, Sarah could only offer one word: “unwanted”. None of her friends or siblings knew she had an abortion, not even her own father – just her mother, stepfather, Adlam and his parents.

Having had an upbringing devoted to God, Sarah turned her back on the church after her termination. “I’d lost my faith, I’d lost my virginity, I’d lost my innocence and I’d lost my self-respect.” She was raised to believe that if she did good things, God would look after her, and if she did bad things, she would go to hell. “I remember thinking, ‘I did all the right things and then this happened to me, so, what does that actually mean?’ Her faith was broken, she says. “I just couldn’t believe in God when life is such a dangerous thing.”

Sarah held little faith in another institution too – the New Zealand Police – laughing when asked if she ever considered reporting Adlam. “Life was very different back then,” she says. “The social disgrace! It’s just your word against theirs, isn’t it, and it is the woman who is looked down upon for actually being a whore. You went from Mary, Mother of God to Mary Magdalene so, no, I never even thought about it.” Sexual violence support services only began to form in Aotearoa in the early 1970s, with no official national organisations until the establishment of Te Kākano o te Whānau in 1985, and the National Collective of Rape Crisis and Related Groups in 1986.

A couple of months after the termination procedure, while the family were staying at their bach in the Coromandel, Sarah’s mother made a derogatory comment about her daughter’s abortion. “She was obviously still very angry with me,” Sarah recalls. Deeply upset by her comments, Sarah was determined to hitch-hike alone back home to Hamilton. “She must have felt guilty about what she said, because she eventually drove me back to our house.” Her mother returned to the Coromandel, and Sarah found herself alone in their family home.

Now barely 17 years old, and feeling uncomfortable being home alone, Sarah phoned two of her close friends. “They came over and we sat there chatting for a few hours – things girls talk about, stupid, irrelevant stuff.” Some time after 10 o’clock her friends went home, and Sarah heard a loud knock at the door. It was Adlam. “I do not recall contacting him, I’m not sure why I would have contacted him, to be honest – but there he was.” Adlam asked if she wanted to stay at his parents’ place for the night, given that she was at home alone.

Sarah was still feeling unsettled about the argument with her mother, and says she still had a detached “go with the flow” approach to her own safety. “I hadn’t even started healing, I was just going where life takes me.” She believed the offer from Adlam had come from his parents, who knew about the experience she had with the termination a few months earlier and may have been concerned about her being alone. “I remember thinking ‘that’s very kind of David’s parents for asking me to stay’.”

It was late at night and the house was dark when they arrived – there was no one else home. “That’s when he made it quite clear that he wanted to have sex with me,” Sarah recalls. “He didn’t ask, he just said ‘oh I’ve got some condoms’ and he took me to the bedroom and I lay there, I just lay there.” She says she remained completely still as he had sex with her four times over the course of the night. “I may as well have been a corpse,” she recalls. “My body was there but my mind was just saying ‘you’re a disgrace’ and ‘what right do you have to say no?’”

In one of Sarah’s personal notebooks recounting her experience, provided to The Spinoff, she poses another question: “I wonder what it’s like to have sex with a dead thing?”

Even as the sun rose the next morning, Sarah hadn’t moved or slept. She felt completely disconnected from her body. “Women who have been through what I went through lose their self-respect – you feel you are already a disgusting person, so you don’t protect yourself properly.” Adlam drove her back to her house. “That was probably the worst thing that happened to me. I viewed it as the ultimate betrayal, especially after what we had all been through.”

When asked about the events of that evening, Adlam says the pair resumed their relationship over the summer of 1974 and that “everything within the entire relationship was consensual”.

After that night, a fellow clarinet student of Adlam’s told Sarah that he had also been “seeing” two other young women that he was teaching, who were at least two years younger than her. She confronted him about it and says he explained that he got different things from the other girls, and she was just used “for sex”. Nearly 50 years on, she still remembers her response.

“That’s when I turned to him and I said: ‘I’m not one third of a person, David’.”

Adlam denied both telling Sarah that the relationship was only about sex, and that he was in a relationship with two more of his students at the time. “I liked [Sarah] very much and feel sorry that she saw it as anything like that,” he wrote. “I believe that we had a reasonably normal relationship for the time (apart from the most unexpected pregnancy) with mutual respect on both sides.” He said that Sarah began taking the contraceptive pill over Christmas 1973 “so that we could have sex relatively safely”.

Sarah disputes this. “I did not go on the pill with David, I went on the pill a huge amount of time later – well over a year – in a completely new relationship.” She recalls that she first began taking the contraceptive pill over 15 months after her experience with Adlam, and was only able to stay on it for about a month because her body could not tolerate it. “It made me so nauseous because of course it was a very high dosage in those days.”

In her final year of high school in 1974, Sarah slowly started to piece her life back together. She stopped playing clarinet and picked up the oboe, and began spending time with a new group of friends who were at various stages of their arts and science careers at university. “These three people, they saved me,” she says. “They let me go to their flat whenever I wanted and they would effortlessly involve me in their lives. I would sit there for hours, just crying silently in front of them while they carried on with their marking and lesson prep.”

Although Sarah never told them what she had been through, there was an unspoken understanding that she needed a safe space to rebuild herself. “They had this unrelenting good humour and laughter and they really did save me.” She went to as few of her lessons in seventh form as possible, and began making plans to get far away from Hamilton and far away from Adlam. “I swore I would never come back here again. Over my dead body.”

The only way Sarah could justify a move away from home to her family was to choose subjects that weren’t available at Waikato university. She travelled to Auckland university for enrolment week, and settled on cell biology and marine biology – two courses she couldn’t do back home. Despite her motivation being primarily to get away from Hamilton, she quickly clicked with the “fascinating” subjects. “I just absolutely thrived. I loved university, I met the most amazing people and had the most amazing teachers.”

Academically she was soaring, but Sarah’s experience with Adlam left her romantic relationships suffering for many years in her young adulthood. “He stuffed it up dreadfully for a long time,” she says. “I had gone from being this totally innocent never-had-sex-ever Christian girl to what I went through… you tend to not look after yourself as well as you should because you don’t feel entitled to.” She describes herself as “a bad chooser for a while there”, referencing a long period of time where she found intimacy extremely unenjoyable.

Although she had moved cities, Adlam had also relocated to Auckland and they had friends in common in the music and university scene. Sarah describes bumping into him at social gatherings and even visiting his flat, recalling an ongoing feeling of numbness when they interacted. “I think when you are young, you don’t understand the power dynamics of relationships, part of you thinks that it was still all your fault that this happened,” she says. “You carry on with this social contact because you don’t understand what’s really happened to you.”

Where Sarah largely abandoned all musical pursuits following her experience in 1973, only occasionally playing the oboe, Adlam went on to have a successful career as a clarinettist, conductor, composer and teacher. He played principal clarinet with the Symphonia of Auckland from 1976 until 1981 and performed regularly on Radio New Zealand. He gained diplomas from Trinity College of London in both piano and clarinet and a Master of Philosophy in music composition from the University of Auckland, cementing himself as an influential figure in the local classical music and music education scene.

“I think when you are young, you don’t understand the power dynamics of relationships, part of you thinks that it was still all your fault that this happened.”

After Sarah graduated from university she spent time working for the department of labour, and then at a halfway house for discharged psychiatric patients run by Catholic priest Felix Donnelly. “I’m fairly introverted by nature but what really surprised and humbled me is that I really love people, just the average person,” she recalls. Combining that with her newfound love of science, she decided to apply for medical school. Sarah began studying in chemical pathology, before moving to psychiatry, and then settling on general practice.

That decision would shape the next four decades of Sarah’s professional life. She went on to become one of the first female GPs working in Mount Eden Prison in the 1980s and 90s, before spending a decade working in remote clinics across Aotearoa, from Whangārei to Greymouth, Te Puia Springs to Fox Glacier.

Now retired and in her mid-60s, she describes her 40 years in medicine as a tremendous privilege. “You get an invitation into people’s lives that you get in no other profession,” she says. Caring for survivors was also a constant reminder of the trauma and secrecy that sexual assault carries with it. “I think there’s a lot of unrecognised harm out there and a lot of women who have been through similar experiences who have never received any help, never received any recognition, some that have been too afraid to tell anyone about it.”

“I remember a few decades ago when I was GP locum, I had this lady come in and tell me about her rape by her father when she was a child. She was 84 years old and I was the first person she had ever told, you know? People didn’t tell.”

In the late 90s, Sarah considered speaking up about her experience after she found out that Adlam was taking up a new teaching position in the music department at Epsom Girls’ Grammar School (EGGS). “I nearly wrote a letter saying ‘do you know this man is not safe around young women’,” she says, “but then I thought, who on Earth is going to believe me?” Still working as a GP, she didn’t want to put her name on it, and if she wrote it anonymously she thought she wouldn’t be taken seriously. “I felt quite powerless to do something about it.”

Following the publication of When the lessons end on The Spinoff, the NZ Herald reported that multiple EGGS students had complained about Adlam’s behaviour during his time there. “He showed interest in lots of girls, like he would be flirty but not like anything you could report. Just kind of creepy,” a source said. The story also said that he was alleged to have been in an “inappropriate relationship” with a student. Adlam told The Spinoff that “insufficient evidence” has been found in regards to impropriety. He left the school in mid-2000.

Having worked in a field that has strict rules to manage the power imbalance between doctor and patient, Sarah says she wants to see more clarity in the private teaching sector. “Everyone has got to be aware: it is a no no, teachers should not have sexual relationships with their students. Thou shalt not have sex with your student, ever, and you must understand the power dynamics.” She hopes that by going public with her story and showing the intricacies of Adlam’s behaviour, and the parallels with Eva’s story from more than 30 years later, more people will feel empowered to share their own experiences.

In June 2022, the Amber Heard vs Johnny Depp defamation trial, and subsequent ruling in favour of Depp, resulted in Sarah deciding to conceal her real name in this story in order to protect herself and her family. “Regardless of the truth, there is going to be an empowered backlash against women by abusive men now,” she wrote in an email the day the news broke. “I feel as if women’s rights have now regressed back to where my story began.”

A week after approaching Adlam for comment on the allegations in this story, The Spinoff received a letter from Adlam’s lawyers, sent on his behalf. “He is concerned that you are contemplating publishing a further article about him that appears likely to contain material that is untrue and seriously damaging to his reputation,” the letter read. “Please be put on notice by this letter that should you publish any material about Mr Adlam that is untrue and damaging to his reputation, we have been instructed to file an action in defamation.”

Sarah, who signed an affidavit confirming her version of events, remains resolute in her desire to speak up. “I can talk about it now, if he wants me in court I can stand up now and tell my story. I wasn’t sure if I could in the past but I can now. I can now.”

Over the course of reporting, Sarah also took her story to the police, who responded quickly to the complaint and provided her with free counselling. Within a week she was called back into the police station, where both the officer she first spoke with and another sergeant were waiting for her in a small room. That’s where they told her that they were unable to progress with her complaint because they were bound by the legislation at the time of the incident.

Given that nearly 50 years have passed since her experience, Sarah didn’t have high hopes for further action – but she was concerned for other survivors of historic incidents. “When they told me that, I thought about how disastrous it could be for a lot of women, that it might stop them coming forward,” she says. “But it shouldn’t, because everything I have said to the police is sitting now there in a file – they may not interview him but the information is all there, and that’s the important thing.”

Now retired from medicine after being “burnt out” by the stresses and demands of the pandemic, Sarah says she has found a new strength and healing in this next chapter of her life. There’s work to do in the garden, books to read, and she’s planning to return to her first love – playing and composing music – after nearly four decades away from it. “I’ve had these bits of music just sloshing around in my head just waiting to be put on paper, so that’s what I’m planning to do,” she smiles. “I just needed time and space again.”

On the second floor of her Hamilton home, there’s a cosy, booklined nook where Sarah is getting reacquainted with music. Two shiny black music stands greet us in the middle of the room, their crisp warranty tags still attached. There’s an instrument fingering chart lying open on one and sheet music on the other. Sarah is learning Schubert’s ‘Ave Maria’, depicted as a prayer to the Virgin Mary inspired by the Walter Scott poem: “Thou canst hear though from the wild; Thou canst save amid despair.”

Sarah gently takes her latest purchase off the shelf and quietly cradles it in her hands. It’s a second-hand clarinet, the instrument she gave up in 1973, that she bought from an antique store on a recent road trip. At the moment, she finds it too painful to play – “it messes with my head and emotions somewhat” – so she is focusing instead on the alto recorder and piano. Normally Sarah practises her music with the curtains open, facing out the window.

Today, the curtains are closed, but the afternoon sun is still peeking through.

*Name has been changed to protect her identity

If the events depicted in this story have been triggering in any way, please consider contacting any of the following organisations: