The government has commissioned an inquiry after forestry waste caused widespread devastation in Cyclones Hale and Gabrielle. But records show experts have been sounding the alarm for decades – why did no one hear them?

This story was first published on Stuff.

Ten minutes into the grey wasteland of the Mangatokerau valley, just north of the East Coast’s Tolaga Bay, Bridget Parker slams on the brakes of her truck and mutters quietly, “oh god look at that”.

She is pointing at a collapsed slab of riverbed, its silty sides littered with the dead trees. The water below is a chalky green. As she watches, a pile of gravel from the road slips further into the stream.

Parker, a farmer who has lived at Tolaga Bay since she was a child, jumps out of the truck, wading through the mud in her sandals, for a closer look. “That used to be our swimming spot,” she says, her hands covering her face in shock. “It was a meadow, the grass sloping down to the edge. We used to bring the kids here for picnics. And now look at it. It’s totally lost.”

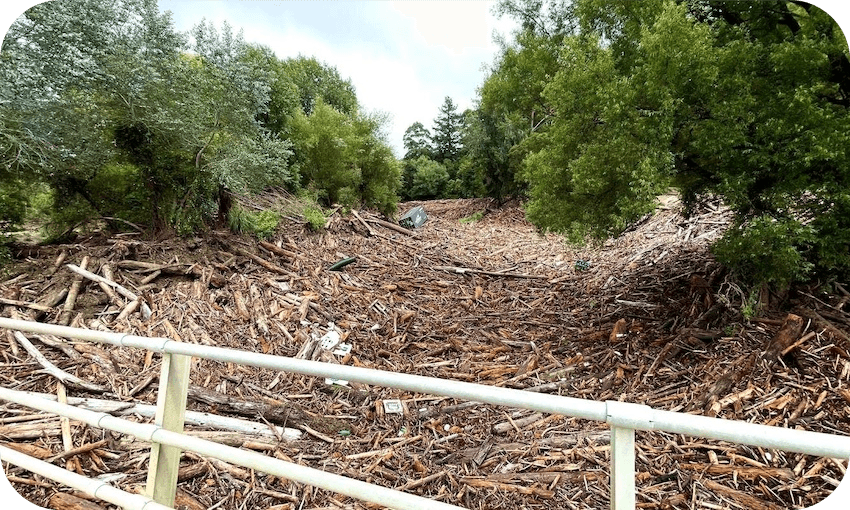

The Mangatokerau river – and its neighbours in the Ūawa catchment, the Mangaheia and the Hikuwai – were wrecked by Cyclone Hale on January 10, then wrecked again by Cyclone Gabrielle a month later. Rafts of full-grown logs and wood slash from the commercial pine forests above careered down the valleys, gouging out the riverbed, smashing bridges and choking rivers, smothering fish, flooding houses, clogging Tolaga Bay’s famous beach.

And alongside the wood: silt, slipping from the steep, unstable harvest sites in great chunks, and washing on to the land below.

Where the rivers merge with the Ūawa river at the fertile, lowland plains there is grainy mud everywhere: it swarms sweetcorn paddocks and swamps fences, seeps across roads, into homes, into cars. It inundated the Parkers’ fledgling kiwifruit orchard, due for its first harvest this March. The silt pile was so deep it took 60 workers digging for a week to get it out. The Parkers sold their stock, unable to feed them on silt-covered grass.

Since 2017, the region has been regularly plagued by floods of wood and silt every time there is a heavy rain event.

During the worst example, severe storms at Queen’s Birthday in 2018 weekend saw 400,000 cubic metres of woody debris spread across the Ūawa catchment. In total, the clean-up across Ūawa cost $10 million.

In response, the council took a series of five prosecutions against companies who managed the forests near Gisborne, accusing them of breaching the Resource Management Act by illegally discharging sediment and woody debris into the environment. On December 9, 2022, Ernslaw One Ltd, which refused to plead guilty for more than four years, was the last of those companies to be sentenced in court.

Judge Brian Dwyer fined the company $355,000, punishing it both for the pollution and for its “obdurate” position, which repeatedly delayed the council’s investigation and the court case.

A month later, logs and silt from Ernslaw’s Ūawa forest site came crashing through the Parkers’ property again.

“We feel as though we are being chased out of our home,” Mike Parker says. His family have farmed in Tolaga Bay since 1958. “We keep saying, ‘don’t we have a right to live here safely?’”

After Cyclone Gabrielle tore through in February, the government announced an inquiry into forestry slash and land use, prompted both by the widespread devastation and the death of a child at Gisborne’s Waikanae Beach on January 25. Witnesses said the 11-year-old boy was hit by a log while playing in the water. The inquiry, led by former National MP Hekia Parata, will run for just two months, concluding at the end of April.

Tolaga Bay residents are among those scrambling for information to present to the inquiry panel. They don’t understand why it has taken so long to come to this point. Because, for years, multiple reports, investigations, and prosecutions have carried warnings about the risk of allowing poorly-regulated forestry on the steep land surrounding their homes and farms.

“Everyone knew about this and did nothing,” Mike Parker says.

The rise of Pinus radiata

Pine trees were first introduced to Tairāwhiti as the solution to a problem: erosion. Pākehā settlers had burned and cleared the indigenous forest, and populated the country with sheep and cattle. But without the tree cover to protect the soil, the steep hillsides began to erode – their soft soils slumping into gullies and, eventually, out to sea.

By as early as the 1950s, it was conceded that the most vulnerable land needed trees back. But instead of reverting to native bush, the New Zealand Forest Service chose to plant the exotic Pinus radiata, a species noted for its rapid growth and ability to withstand harsh conditions, and already in use around Aotearoa as a replacement for native wood. The Crown began to buy pockets of land – both in Gisborne and in the erosion-prone Tasman region – to turn into “protective” forest.

Then, in 1988, Cyclone Bola hit. The storm completely devastated the pastoral hill country, with landslides scarring almost every slope.

To prevent more damage, the government subsidised a mass planting scheme in Tairāwhiti called the East Coast Forestry Project. Private investors rushed to take advantage, in hope of huge returns. At the same time, the Crown sold the cutting-rights to its own forests, including those first planted as erosion protection. By 1997, 27,0000 ha of paddocks had been replanted in exotic forest. By 2020, there was more than 150,000ha in radiata on the East Coast.

Pines take 28 years to mature. For years, as harvest grew near, forestry companies nationwide were required apply for consent and meet the individual consent conditions of each council, which varied by district. But as the mass of post-Bola plantings in Tairāwhiti grew ready for felling, the companies began to push back against the regionalised regulations. They wanted national guidelines, to save time and money.

In 2009, the minister for the environment, Nick Smith, asked the ministry to look into the creation of a national environmental standard for forestry (NES-PF). Straight away, Gisborne District Council mayor Meng Foon pushed back, asking the ministry not proceed with the idea.

“The key reasons for the request are the likely adverse environmental effects in the Gisborne District,” Foon wrote. The region’s shallow, erosion-prone hills needed site-specific controls, he said, not a one-size-fits-all rule.

By 2015, the proposal was raised again by the Ministry for Primary Industries.

The councils opposed it. One called it fundamentally flawed. Another labelled it an “industry led proposal driven by industry for the benefit of industry.”

Gisborne council was critical that it relaxed rules on all but the sharpest slopes, meaning forest owners would be able to harvest on huge swathes of erosion-prone land without a consent covering specific details of how they would mitigate against landslides.

The council repeatedly tried to make the point that it needed the ability to set conditions to protect the environment, particularly given the known issues with what scientists call the “window of vulnerability” after a clear-fell harvest, when all the trees are cut down.

According to Landcare Research scientist Mike Marden the “window” of risk lasts about eight years. It’s the time when neither the roots of the harvested trees, nor the roots of any new trees planted, are capable of stabilising the soil, and there is no canopy cover. If a storm hits, the land is completely vulnerable.”

“It’s during this period that foresters cross their fingers and hope that there’s not another cyclone,” Marden says.

Cyclone Cook struck Gisborne at Easter 2017, after harvest of the Bola-era plantations had begun. Floodwaters dragged waste downstream, with slash and logs clogging the Ūawa catchment.

Afterwards, Gisborne District Council principal scientist Murray Cave wrote a report warning that forestry debris was likely to cause huge damage in another big storm.

Cave found the foresters were not following best practice. Slash piles known as “birds’ nests” were routinely stored on flood plains and future downpours would cause risk for buildings and infrastructure. Slash traps meant to catch the debris were overwhelmed or had failed. Earthworks next to streams did not have the safeguards required to stop sediment reaching streams.

Cave recommended the council “where practicable” review harvest consents to ensure they were fit for purpose, and that it ramp up its compliance and monitoring arm.

However, he said the council would also need to find new environmental tools to address the issues, as they were not “fully addressed” by the guidelines in the new national standard, which had been finalised in August 2017.

‘You can’t afford to fight us.’

One day shortly after Cyclone Hale hit in January, Bridget Parker came across two managers from forestry company Ernslaw in her orchard. “What are you doing here?” she asked. The pair were inspecting the damage. Parker asked them to help clean up the mess. Ernslaw agreed to pay for removing the logs from the orchard, but not the silt.

Up and down Tolaga Bay, the stories are the same. After 2018, forthcoming help from some of the companies was extremely slow. They quibbled endlessly over what proportion of the wood on the beaches was from forests, and what was natives or other species like willows. The council later found 85% came from pine forests.

When pushed, some of the companies ended up paying landowners partial clean up costs. Permanent Forests, for example, paid Paroa Station owners $388,000 for the damage and clean-up work. But the station owners estimated it would cost up to a further $175,000 to remove the debris. All of the companies faced further fines in court.

At Linda Gough’s house in the Mangatokerau valley, mud has taken over the entire property. It stinks from the puggy silt and the toilet no longer works. Gough has lost her garden, her fruit trees. All her fences are down.

Civil Defence convinced Gough and her family to move out, after she started getting chest pains from stress. Gough had been arguing with Aratu, the company who owns the forest upstream, to come and dig their property out.

“Imagine if we put that amount of silt and logs on their property,” she says. “And yet they say we are ungrateful because we complained they haven’t come to fix our driveway because they helped dig out a bit of mud weeks ago.”

In 2018, it was even worse, Gough says. The forest owners’ lawyer turned up on her doorstep to negotiate a payment, Gough says. When she told them the offer was too law, and she would take them to court, she says she was told they would just drag it out because “we know you can’t afford to fight us.”

Forestry have all the money and all the power, the Tolaga Bay locals say. During the national standards’ formation, they constantly pushed for weaker rules, according to former Gisborne District Council environmental services manager Trevor Freeman, who was on the working group.

In the prosecutions taken after 2018, the court highlighted the companies’ attitude to the laws they helped create. The forest owners’ had not taken necessary precautions to prevent the damage caused by their practices, the court found, even though they could have. The judge suggested this was because of the cost.

In one instance, he said, Ernslaw had even written a letter to the council outlining the costs of preventive work it could undertake. “Ernslaw obviously reached the view that the economics of these measures were such that it was not practical to take them,” judge Dwyer found. The court noted Malaysian-owner Ernslaw was one of the largest forest owners and the second-largest private landowner in the country, and had earned $53.8 million between 2014 and 2018.

The forestry owners’ deep pockets afford them a long reach: they can hire expensive public relations firms, hold flashy events, write economic impact reports about the importance of forestry for earnings and employment. In 2013, industry lobby group Eastland Wood Council (EWC) produced research arguing it employed 10% of the regional workforce.

Forestry’s contribution to the economy also affords them access to politicians. In 2022, the industry’s national body, the Forest Owners Association, had regular catch-ups with minister of forestry, Stuart Nash. Diary entries show he even attended their board meetings.

On the flip side, when he was in Gisborne after Cyclone Hale, Nash held a meeting with forestry stakeholders and the council, to which local landowners were not invited to attend.

This upset Mana Taiao Tairāwhiti, a group representing landowners, iwi, and environmentalists, who had just presented council with an 8,000 signature petition asking for a forestry inquiry.

Nash had earlier rubbished the inquiry idea, saying the forestry industry was best placed to self-regulate in conjunction with councils. This response – and the fact Nash had previously taken large electoral campaign donations from forestry-related companies – gave rise to allegations he was a forestry apologist, which he strenuously denied.

But Mana Taiao wasn’t convinced: A week after prime minister Chris Hipkins overruled Nash and the inquiry was announced on February 23, Nash was still pushing forestry industry talking points. On February 26 he told Q+A: “Keep in mind, about one in four families up and down the East Coast rely on the forestry and wood processing industry.”

This week, Nash refused to answer why he had attended a Forest Owners Association meeting, only saying he regularly met with stakeholders. He also didn’t explain why he resisted an inquiry for so long. Instead, he said forestry “is and will continue to be a significant contributor to the Te Tairawhiti economy.”

‘I can’t recognise anything’

At the Mangaheia River, Mere Tapanui (Ngāti Patuwhare, Te Aitanga a Hauiti) is measuring the water quality with students from Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Mangatuna. They lower a bucket from the bridge into the water and pull it out. It is cloudy and warm.

The fish like it to be under 20 degrees, Tapatio says. “The warmer temperatures and the sediment are suffocating them.”

Tapanui has been monitoring the stream for ten years. Since 2017, after Cyclone Cook hit, she has noticed other changes linked to the increased waste in the river – the eels are getting smaller, there are fewer whitebait and shrimp and mullet – all food sources for the locals put at risk. Today, she wants to check on the health of the mussels too, but she can’t get down to the water because of the slips, and is worried she will get caught on one of the logs jammed in the stream bed.

Instead she focuses on the lesson for her students. She tells them she can see the remnants of the traditional kūmara gardens at Paroa, and further away, the remnants of marshy grounds where wetlands used to be. Further up the river was the spot that was the hapū’s “olympic swimming pools” she says, although the storms have wrecked that.

“What can you see?” Tapanui asks the children.

Karma Jane Thatcher, who has put mud from the river on her face like war paint, squints at the ruined landscape of silt and log litter. “The problem is I can’t recognise anything,” she says.

Before Pākehā arrived in Tolaga Bay, the steepest hillsides were covered in thick native forest, with the lower hills clad in sparse scrub. The plains and frost-free hillsides were cleared for gardens and housing.

Mana Taiao members like Tapanui, and former Gisborne District Councillor Manu Caddie say it’s time that thick native bush was encouraged back on the steepest slopes – not for harvest, but to hold the hillside together and preserve what land is left.

“Diverse native forest is the best, perhaps only land-use option for remote, erosion-prone landscapes,” Caddie says. “Even with native regeneration there will still be uncontrollable erosions, but we can save a lot of land that is otherwise turning into a moonscape.”

Forest Owners’ Association spokesperson Don Carson said they were anticipating that as a result of the inquiry, some steep land would need to be retired. But that would be expensive, he said, and difficult, as natives were much harder to grow than pine. Then there’s the question of who pays.

“If the government requires managed retreat from that land I think the companies would expect compensation for doing so,” Carson said.

Part of the opposition to phasing out clearfell pine is the consequence for employment. Work has always been part of the industry’s sales pitch, and still is. Whether its promises have come true, however, is a matter of opinion.

Forestry is largely contract work. When there’s thinning or harvesting to be done, the money isn’t bad. But if the crews are stood down – when the log price drops, or after a storm – there’s no pay. For example, in the weeks after Cyclone Hale, Gisborne’s Ministry of Social Development office was faced with workers that had been laid off, wanting help finding new jobs, or applying for welfare.

“People thought it would create jobs for the young men,” says Sarah Gibson, 91, who has lived in the village for 70 years. And at first, there were jobs, she says. But after the initial planting was done, the work dried up and all those young men started to leave.

Back then, Gibson says, Tolaga was a thriving township. All the shops were open. On Friday nights the farmers and their wives would all come into town, it was humming . Now, the streets are empty, the shops boarded up. “Our town is dead,’ Gibson says. Out here, it’s hard to see where the cash from the $6billion forestry industry is ending up.

The forestry industry rejects the idea it destroys communities and jobs, citing a 2020 report commissioned by MPI that showed forestry had a larger economic value per hectare than pastoral farming.

The right tree in the right place

A complete retreat from commercial pine seems unlikely in the imminent future: there is too much money involved. Both independent experts and the Ministry for Primary Industry say it’s also unnecessary, but agree that some change needs to happen rapidly, particularly in the face of the likelihood of more extreme storms to come due to global warming.

Landcare scientist Mike Marden says instead, there should be a partial retreat – from the steepest hillsides, and nearest the water. Those are the areas that should be allowed to revert to natives like Kanuka. Already some companies, such as Aratu, have begun to creating wide strips of natives along rivers, to reduce risk. And it’s not only about reducing pine: Marden says more land still in pasture should also be given over to native bush.

“This isn’t the death knell for forestry,” he says. “It’s more about getting the right tree in the right place, and changing practices, so we aren’t stripping an entire catchment at one time.”

Marden says much of the damage on the East Coast and Hawke’s Bay could have been avoided if expert advice and warnings had been heeded earlier, about the danger of planting all the same crop, at all the same time, everywhere, right down to the rivers.

“Everyone was in such a hurry to prevent further damage,” he says. “The absence of foresight in recognising that harvesting would undo the erosion control and other environmental benefits accrued during the growing phase, has led to unintended consequences.”

He hopes the inquiry will avoid making the same mistakes again.

Meanwhile, the risk to the residents of Tolaga Bay remains. Even though the recent cyclone washed some of the slash out, there is more still trapped in the hills, waiting for the next storm.

“I can’t even think about that,” Parker says. She shudders. “That scares the hell out of me.”