Yesterday Auckland Council voted unanimously to endorse the rāhui placed by local iwi Te Kawerau ā Maki on the Waitākere Regional Park, and close all walking tracks to help fight the spread of the deadly kauri dieback disease. Edward Ashby, the executive manager of Te Kawerau ā Maki, explains what it’s all for.

New Zealand is known for its ‘clean green’ brand and New Zealanders love the outdoors and our wilderness spaces. It is part of our cultural DNA to spend the summer at the beach or tramping through the bush. Our natural environment is also the central pillar of our multi-billion-dollar tourism industry. While the natural environment is a core part of our identity, lifestyle and GDP, there is a severe deficit in what we invest back into nature – both fiscally and socially. The inevitable result is an environment in decline. This is true of the Waitākere Ranges where millions of visitors pour through the forest each year extracting experiences yet giving nothing back to the forest. The situation is worsened when under-investment is combined with a deadly pathogen.

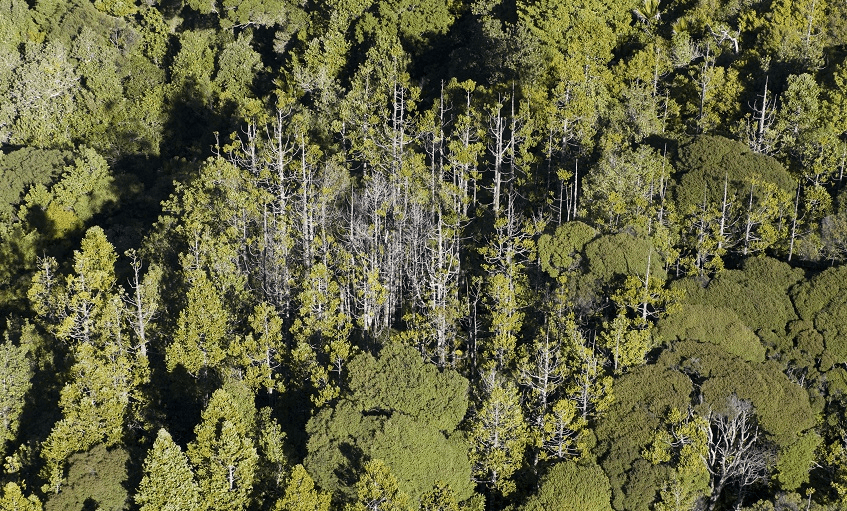

Kauri dieback disease has a long but uncertain history. Its presence in Waitākere was confirmed in 2008, though it may have been there longer. There is a lot still to learn about the disease. What we do know is that phytophthora agathidicida (aka kauri killer) lives in the soil for years, loves water, and attacks its host through the roots eventually starving the tree to death from the inside out. The result is 1000 year old trees – some of these giants have been here longer than humans – dying within a few years. On our watch. We know it is spread primarily by humans (70% of infection in Waitākere is within 50m of a track) as we move infected soil around the forest on our shoes. Pigs and poor track design contribute as well. We also know there is currently no cure.

In mid-2017 Auckland Council released a report that outlined that approximately 20% of kauri in the Waitākere forest were infected with kauri dieback, and that nearly 60% of kauri stands over 5 ha were infected, meaning Waitākere is facing mass habitat and biodiversity loss. Worse still is the fact that the infection rate had doubled within the past five years. It doesn’t take a math genius to figure out that, at the current rate of deaths, there could be localised extinction of kauri within a generation. The impact doesn’t stop there. Kauri are keystone species – they create the conditions in which they thrive by changing soil chemistry, hydrology, forest canopy, and ground cover which creates the habitat and conditions for a large number of co-dependent plant, fungi and animal species. In essence, if we lose kauri we lose the forest altogether. Fast growing replacements such as manuka and kanuka do not hold the same habitat value, and are themselves the targets of the vile Myrtle Rust disease.

Kauri is an iconic species and national taonga (treasure). It is one of the oldest species of tree in the world, and kauri forests are some of the oldest forests on earth. Its natural distribution is roughly the upper half of the North Island, taking in Waikato, Coromandel, Bay of Plenty, Auckland, and Northland. The fight against kauri dieback is supposedly led by the National Kauri Dieback Programme (NKDP) set up about a decade ago. The NKDP is led by the Ministry of Primary Industries, with DOC and regional councils as partners. There is also a Tangata Whenua Roopu that is an advisory board on matters of tikanga and mātauranga Māori. While the NKDP did make some positive steps in the early days, its current function, management, research programme and relationship with mana whenua as Treaty partners is questionable at best, and a dysfunctional and broken barrier to progress at worst. Auckland Council as a member of the NKDP is bound to this bureaucracy while also having responsibilities under its own auspices. Despite the money, tools, resources and time at the NKDP and Auckland Council’s disposal, the death rate doubled and meaningful engagement with mana whenua was for all intents and purposes non-existent.

This is the context in which Te Kawerau ā Maki, the iwi with mana whenua over West Auckland, was forced to try and navigate until deciding to act directly on behalf of Waitākere forest – Te Waonui a Tiriwa – by placing a rāhui, or cultural quarantine, over the forested area of the Waitākere Ranges. The decision was not taken lightly, but was taken to ensure that the forest and kauri are still standing for our grandchildren in the future. A rāhui is many things and is a deeply spiritual matter for Māori. It is implemented for a variety of reasons and is a sacred means of managing an area or resource. Employed as a method of what might be termed indigenous conservation, the rāhui over Waitākere is a means to protect the environment and allow time for the forest to heal, to stop the spread of kauri dieback, to allow time for remedial works and infrastructure upgrades to make access safe, and to buy time for scientists to come up with the tools to manage or kill the disease.

The Waitākere rāhui is one of the largest indigenous conservation efforts in New Zealand. It is certainly the largest and most unique rāhui of this kind in living memory, given the size and complexities of the Waitākere Ranges. It also sits at the heart of a debate around the role of kaitiakitanga (the sacred obligation of mana whenua guardianship) in the 21st century and the role of the Treaty of Waitangi in how the Crown and Māori work together on conservation issues.

Among other things the Treaty provides for the protection of Māori and their taonga. Te Kawerau ā Maki have gone on record stating that kauri dieback is an existential issue and that if the forest dies so too does the iwi. The obligation on the Crown is to protect both the iwi and kauri. The principles of the Treaty are captured in a number of relevant pieces of legislation. The RMA (1991) directs local authorities to account for the exercise of kaitiakitanga. The Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area Act (2008) specifies that the Waitākere Ranges are nationally significant, require the Crown and Auckland Council to protect and enhance its heritage features, and recognises Te Kawerau ā Maki as tangata whenua including their responsibilities as kaitiaki. The Te Kawerau ā Maki Claims Settlement Act (2015) recognises Te Kawerau ā Maki mana whenua (and kaitiakitanga) over Waitākere, apologises for nicking the land and chopping the trees down, and gives additional statutory recognition over much of the Waitākere Ranges. The Auckland Unitary Plan also provides tools for recognising kaitiakitanga and the need for shared decision-making over matters that directly impact mana whenua.

Auckland Council have been slow to respond meaningfully and boldly, but to their credit they have done demonstrably more than any other Crown organisation. It was after all Council’s own report that provided the evidence on which Te Kawerau ā Maki acted. Their 5 December decision to keep the forest open not only failed to protect kauri and sent the public a mixed message, but failed to live up to their obligations as a Treaty partner. It is a cause for celebration that Auckland Council voted unanimously to rectify this on the 20th February, with a decision to close the forested area of the Waitākere Regional Park (with exceptions to be worked through). Less impressive has been the response and engagement of the NKDP and the Crown. To date, Te Kawerau ā Maki have not been formally and meaningfully engaged by either since placing the rāhui on the 2nd December. The silence has been deafening and our forests are the worse for it. New ministers in a new government are of course very busy people, but it is difficult to imagine what reaches the benchmark of their notice and engagement if the country’s largest rāhui and indigenous conservation effort does not meet the grade. In my experience I lay most (not all) of the blame at the feet of the inept NKDP which has only blocked action in Waitākere in recent years and has refused to engage meaningfully with Treaty partners.

The Waitākere rāhui has given us all an opportunity to pause and reconsider our relationship to our environment. It is part of us, our identity, our economy, but it is very sick. We are in the midst of a positive and constructive national debate about the quality of our lakes and rivers, of our clean green image. We also need to have a genuine debate about the health of our native forests. We need a national policy statement on forest health. This will enable us as a nation to better manage and look after our forests, perhaps to consider them as integral national infrastructure requiring protection and investment.