With government officials, community leaders and the Crown coming together on the day of commemoration for the New Zealand Wars, it could have been a time to examine the wounds of colonisation. Instead, everyone patted themselves on the back, writes Laura O’Connell Rapira.

One hundred and eighty-three years ago, on October 28, northern rangatira signed He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni, the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand, in Waitangi.

The document asserts that the mana and kīngitanga in Aotearoa was to be held fully by Māori, and that non-Māori would not be allowed to make laws for this land and the people living here without the full consent and permission of Māori. It stated that Māori leaders were to rūnanga at Waitangi in autumn each year to discuss and enact laws, and that a copy of the declaration would be sent to the King of England to ask him to act as a matua for our newly established sovereign nation.

Often referred to as just, ‘He Whakaputanga’ the document was drawn up after Ngāpuhi chiefs appealed to the Crown with concerns about the drunk and disorderly behaviour of some European settlers, and a request for their leaders to take responsibility for their people.

The British government had appointed James Busby to be an official ‘British Resident’ here. He drafted the declaration because the British were worried that France or the United States might try to conquer New Zealand.

The declaration was officially acknowledged by the British Crown at the time. Busby called it the “Magna Carta of New Zealand: a statement of sovereign authority that set limits on the power of outsiders”.

Then in 1840 some Māori rangatira signed a second document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Ngāpuhi leaders say Te Tiriti was a confirmation and enaction of He Whakaputanga – two sovereign societies agreeing to live together in this land but with Māori to retain the rights to have rangatiratanga over their/our land, villages and treasures, and the Queen to gain rights to govern European settlers in Aotearoa. Te Tiriti guaranteed that Māori spirituality be protected and that everyone in Aotearoa enjoy the same rights under protection from the Crown.

Māori motivations to sign both documents were, and still are, clear. It was about creating a working and strategic relationship with the British. It was a promising agreement that was broken by the Crown almost immediately as settlers began forcefully taking (or questionably acquiring) Māori land, locking up Māori who rebelled against colonisation in cave prisons, banning and punishing Māori children for speaking te reo Māori in schools and prioritising Christianity over Māori spirituality by funding missionary schools throughout New Zealand.

It was this historical backdrop that I held in my mind, when I received an invite from Government House to attend an event with the Duke and Duchess of Sussex to celebrate 125 years since women won the right to vote in the settler government’s democracy. A right that isn’t actually available to all women since people in prisons cannot legally vote.

The event was held on October 28 – a day that is supposed to be a remembrance for the New Zealand Wars. A date chosen because it marks 183 years since we declared our independence. A commemoration that was hard fought for and long won by Māori activists, but is underfunded, underreported and not a public holiday so it’s likely most New Zealanders don’t know that a “New Zealand Wars” day even exists.

Imagine if we treated ANZAC Day with the same ambivalence. Imagine if we resourced the remembrance of the wars in this land the same way we resource our celebrations of the suffragettes. Imagine if Parihaka peace movement leaders had a place on one of our banknotes just like Kate.

I RSVP’d, still not totally committed to going, and then put up a Facebook post asking friends and whānau to give me a compelling reason to go or not. I got 82 comments – a mixture of “Go, it will be a great story to tell your future kids”, “Go for the free food” and “Don’t go, the British Crown are imperialists and Harry promotes militarism”. I always appreciate the different perspectives I get when I crowdsource wisdom.

I decided to go after a friend suggested I look at what my tūpuna did in relationship with the Crown and take guidance from them. I took my lead from Dalvanius Prime, the driving force behind ‘Poi E’ who used old-school crowdfunding methods to get the Patea Māori Club to England to perform for the Queen, and Dame Whina Cooper who led the land march in 1975. Both of them engaged with the Crown to advance the rights of Māori. I figured I should try and do the same – though I was realistic about how much advancement could happen.

The event was a little bit of a disappointment. There’s been a lot of rhetoric from the National Party and some commentators lately that the government’s working groups are just well-resourced “talk-fests”. But in my view, this was the real talk-fest. The working groups have been a welcome form of participatory democracy, usually held in community halls and public libraries with a diverse range of New Zealanders talking about stuff that really matters and the decisions that affect our lives.

At Government House, there were around 150 of us, mostly women, dressed in our Sunday best. We were served fancy champagne, rose gin and pinot noir by wait staff in snow white uniforms while we waited for the royals, the excellencies and the prime minister to arrive. When they did arrive, the governor-general gave a speech that wove in te reo Māori, mentioned that New Zealand continues to lead the western world in having women in positions of power (three female prime ministers and three female governor-generals) but also that we have horrific domestic violence rates and “unconscious bias” (aka racism) so there is still work to do. It was a good speech.

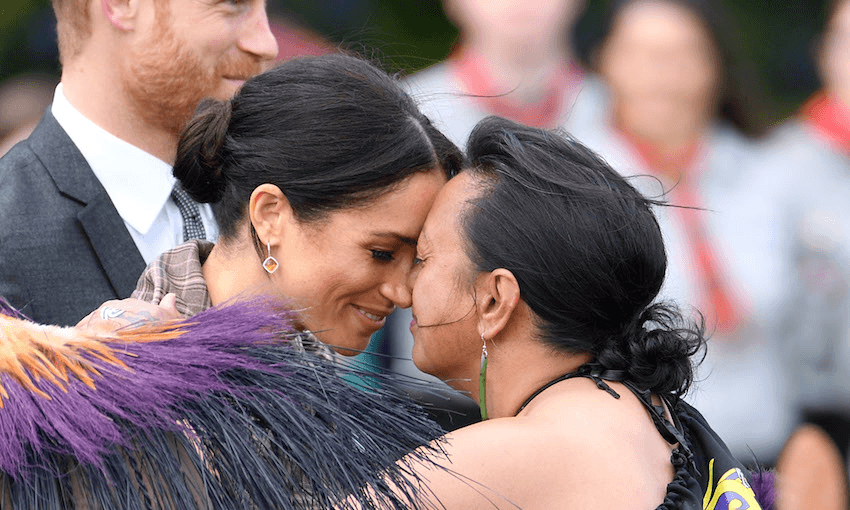

Then Meghan Markle took the stage and greeted the crowd with “Tēnā koutou katoa” to thunderous applause that was reported by every mainstream media outlet in the country.

Maybe I’m just getting tired and cynical, but I don’t understand why so many people clapped or why this was headline worthy. Was it the free wine? Was it the fancy building and the gravitas of royalty? I like Meghan and a lot of the work she is doing to advance women’s rights but I’m trying to imagine an equivalent where Jacinda Ardern gets applause for saying “Bonjour” during a speech in France and I just can’t. Why are we setting the bar for engagement with us so low that we congratulate what to my mind should be the bare minimum?

There was a poem from New Zealand Poet Laureate Selina Tusitala Marsh, then the prime minister and the royals dispersed to talk to people in the crowd. The event finished with a kapa haka performance from a local kura kaupapa.

The performances were lovely, the food (if you weren’t vegan) was nice, and the free booze was great, but ultimately I think the event was a lost opportunity. We had a room full of 150 activists, change makers and creatives and there was zero attempt made to enable meaningful kōrero between community leaders and the Crown. Most of us will be on small salaries, if we’re getting paid at all, and for us to turn up at an event such as this there are actual costs involved. The travel, the outfit, the accommodation, the emotional labour. I don’t think our community investment was matched by the Crown.

There was zero acknowledgement that prior to colonisation, women in Aotearoa had much more than the vote – mana wāhine had equal status and power to mana tāne in Māori society. There was zero acknowledgement of the role colonisation played/s in our horrific domestic violence stats. There was zero acknowledgment that while we may have had six women in leading political positions of power, all of them are Pākehā women.

That’s why this was a lost opportunity. We could have had a reflective and honest conversation about our history with some imaginative ideas about our future powered by people with insights from life on the ground. Instead it felt like a giant pat on the back that obscures our past and did very little to connect the Crown to our present.

We will not heal this country of violence until we acknowledge and heal from the violence (and racism) upon which it was was founded. Of all days to practice that healing and acknowledgment, you’d think an event between the Crown and New Zealanders on October 28 should have been exactly that.

Sadly, it wasn’t.