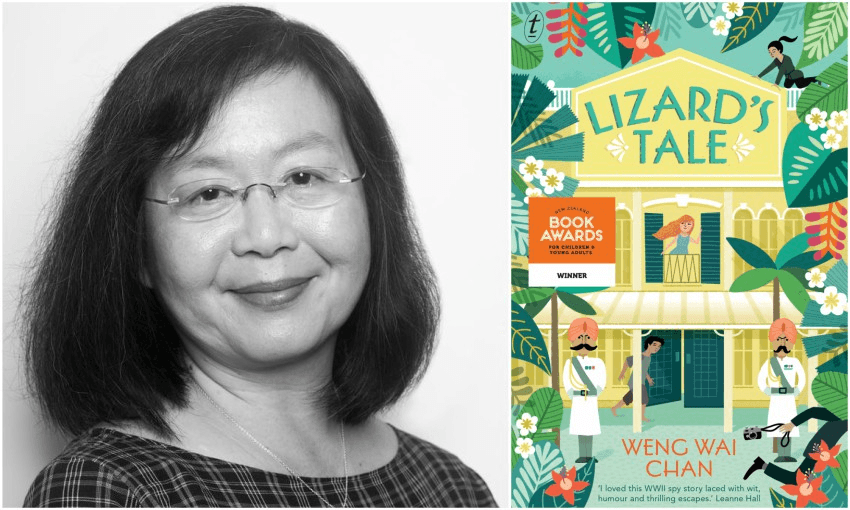

An adventure story that splits the difference between action-packed intrigue and touching melancholy, Sam Brooks reviews Lizard’s Tale, which has just won the Wright Family Foundation Esther Glen Award for Junior Fiction.

When you think of settings for a children’s novel, the dawn before the dusk of the Second World War in Singapore is probably not one that comes readily to mind. And yet, that’s exactly where Weng Wai Chan’s debut finds itself. War as a setting for children’s fiction is one of those dicey things; done right, it’s a way to introduce young people to that unfortunate reality (to wildly understate what, you know, war is) through carefully crafted stories rather than the brutal fist of fact.

It’s perhaps fitting that the setting of Lizard’s Tale – 1940 Singapore, just before the British surrendered the colony to the Japanese – is its largest and most primary asset. The book follows Lizard, a 12-year-old who lives from hand-to-mouth after his guardian, Uncle Archie, went missing. He’s offered a one-off job that’s worth a year’s rent: go steal a box from a hotel room (Raffles, natch). It is, of course, not just a box, and from there the children’s novel follows a winding path of gentle twists and calm intrigue.

Chan fills her novel with rich detail, mixing the signposts of Singapore that anybody vaguely familiar with the country will know (Raffles Hotel, the Singapore Sling) with the more intimate details that locals love to be reminded of and strangers will be endeared by (it is always wet, and always hot). This is especially strong in the opening chapters, where we follow Lizard on his trip to and from getting his box; Chan has a great sense of this location, and how to make it feel lived-in:

“This was home now – Chinatown, with its poles of washing hung out of the windows, the fruity stench rising from the open drains on the sides of the road and the clamour of hawkers hustling in their dialects. The upper floors of the shop houses jutted out over the street, forming a covered walkway along the roadside. Sir Stamford Raffles had decreed that this walkway be five foot wide, and everyone called it the five-foot way.”

These kinds of set-ups are key to the novel’s success and lends the whole story an enchanting feel. It’s not the cold, photographic lens of a tourist guide, but the painterly canvas of someone who knows this place as well as they know an old friend.

The other big asset of Lizard’s Tale is how action-packed it is; this is a book where the plot doesn’t slow down, and with each page comes a new kick, a new twist, a new development. Sure, that sounds basic, but the way that Chan builds her relationships at the same time as throttling through the narrative at fifth gear is the kind of work that can easily go unnoticed. Before the reader really understands it, we totally understand the precarious, tenuous relationship between Lizard and Lilli – two people finding their way to a deeper, more meaningful friendship while also being trapped into their circumstances by spies, foreign plots and the looming spectre of war. People say “show, don’t tell”, but Chan tells with such breathless speed and energy that the showing is actually in the telling. For the most part, she ushers the reader through her story as assuredly as she guides them through her setting.

The one downside of so much story is that the novel definitely feels on the longer side; a potentially spine-gripping climax is truncated to a few paragraphs, while other scenes are so stuffed with character names (having two characters with names that start with Li- is mildly, but not overbearingly, confusing) that you long for a pronoun every now and then. The choice is understandable. Chan swaps around viewpoints so frequently that a name to anchor is definitely helpful, but it leads to some awkward roadblocks in the story’s momentum.

For me, the most remarkable, and special thing about this book, is the touching melancholy of it all and how it sneaks up on you. To be real for a moment: a story that’s set in 1940 in Singapore that wraps up before 1941 has a hypothetical fourth act that isn’t going to get any better. The worst for these characters is yet to come. The novel glances ahead in a way that’s appreciably light – it’d be a lot of weight for even an adult novel to carry, but it’d be unbearable for a novel that’s aimed at children. Chan handles this well. She’s written an introduction to a period and a place that many children won’t be aware of, but she doesn’t force the truly difficult detail on the reader. People in the know – perhaps guardians reading alongside – will be aware that things get worse for Lizard and Lilli, leaving the onus on them to begin the further, more difficult conversations.

Lizard’s Tale, by Weng Wai Chan (Text Publishing, $21) is available from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.