Glen Campbell’s classic hit “Galveston” – what was that all about, and where the hell is Galveston, anyway? Karl du Fresne goes exploring in his new book about the birthplaces of American songs.

We arrived in the city that inspired Jimmy Webb’s song “Galveston”, a hit for Glen Campbell in 1969, not knowing quite what to expect.

Galveston occupies a low-lying island – once the headquarters of the French pirate Jean Laffite – on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, 100 kilometres southeast of Houston. The only person we knew who had been there told us all he remembered was petroleum refineries.

It’s true that you see refineries as you approach Galveston, but they’re in nearby Texas City. Galveston is a different proposition altogether. Seawall Boulevard, the four-lane esplanade that runs for 16 kilometres along the Galveston foreshore, has an almost Riviera-like atmosphere.

It was famous in the 1930s for its casinos and amusement parks and retains some of that character still. A constant stream of traffic rolls along the Boulevard, which is lined with hotels, bars, restaurants and condominiums. Bathers crowd the sandy beach and fish are jumping in the shallows, attracting the attention of cormorants and pelicans.

It seems the archetypal resort city, yet there’s a sober reminder that this sparkling, benign-looking sea hasn’t always been kind to Galveston. A sculpture on the sidewalk above the beach depicts a man and a woman standing together. The man’s arm is outstretched in what appears to be a gesture of despair and anguish; the woman anxiously clutches a small child.

The statue commemorates the deadliest natural disaster in American history, the Galveston Hurricane of 1900. It struck with little warning: Cuban weather forecasters saw it coming, but official contact with Cuba had been severed following the Spanish-American War two years earlier and as a result, Galveston was unprepared.

The island was submerged as enormous seas surged over it, sweeping buildings into Galveston Bay beyond. Estimates of the death toll ranged from 6,000 to 12,000. (By way of comparison, Hurricane Katrina, the worst storm of the modern era, took 1833 lives in 2005). Unable to bury the victims, authorities loaded them onto barges and dumped them at sea, only for most to wash ashore again. In the end the bodies were burned where they lay.

At a Catholic orphanage, nuns roped themselves to children as they sang a traditional French fishermen’s hymn to the Virgin Mary, imploring her to keep them safe. They were found days later, buried in the sand. One by one the dead children were revealed as searchers yanked at the rope, leading eventually to the body of the nun to whom they were all secured.

Galveston never fully recovered. The 5.2 metre-high seawall from which the boulevard takes its name was built to protect the city from the sea and the entire island was raised by pumping in sand and slurry from the Gulf.

Every surviving building was elevated using hydraulic lifts. The massive engineering project took six years, but in the meantime the city suffered another crushing setback with the completion of a channel that provided ships with direct access from the Gulf to Houston, thus bypassing what had previously been Galveston’s busy port. The city went into gradual decline.

Drive one or two blocks back from the bustle of Seawall Boulevard and you see a different Galveston. The streets are empty and many of the once-grand southern mansions look forlorn and neglected. Hardly anything was moving in the 36-degree heat on the day we looked around.

Downtown Galveston, or what little that remains of it, retains a sleepy, faded, Southern charm; you can tell from the restored Grand Opera House that it was once a much more vibrant place than it is now. On the night we were there, Steve Martin – best-known as a comedian and actor, but also an accomplished banjo player – was performing with his bluegrass band the Steep Canyon Rangers.

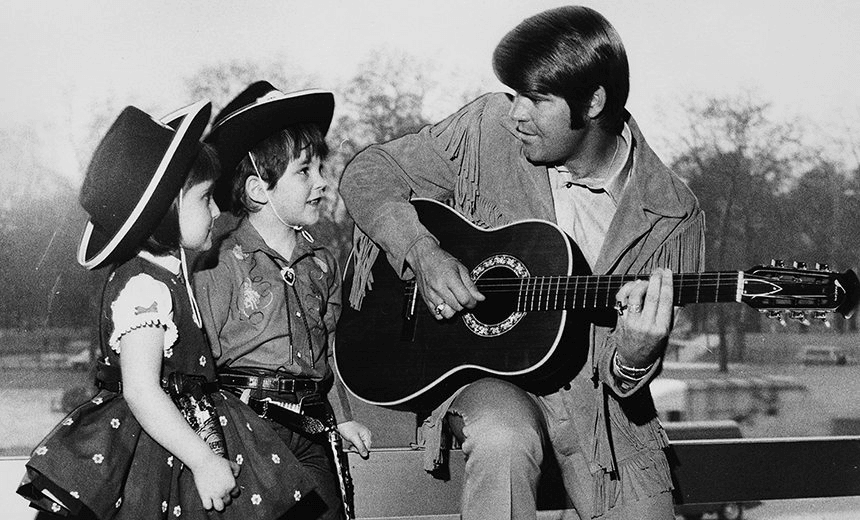

PHOTO: GLEN CAMPBELL ENTERTAINS CHILDREN WITH “GALVESTON”

The song that brought us to Galveston was one of three that Webb wrote for Campbell. It’s written from the point of view of a young soldier who’s away fighting a war. A melancholy elegy addressed to the soldier’s home town and the girl he left behind, the song is full of references to Galveston: the wind, the waves, even the seabirds. As he watches the cannons flashing, he cleans his gun and wonders whether his girlfriend is still waiting for him.

It’s commonly assumed that the song relates to the Vietnam War, which was raging when Campbell recorded it, but it could be any war. In fact, Webb has said he was thinking of the Spanish-American War.

More conventionally structured and arguably more commercial than many of Webb’s songs, “Galveston” ends with a twangy, Duane Eddy-style bass guitar solo similar to the instrumental break in “Wichita Lineman” (in both cases, played by Campbell himself).

I interviewed Campbell in Wellington in the summer of 2006. The night before, he had performed to an enthusiastic crowd in the Michael Fowler Centre. His oldest daughter Debby – a competent enough singer, though hardly in her father’s league – shared the bill. Campbell’s performance, on guitar as well as vocally, was a tour de force that belied his age (70 at the time).

I had been under the impression that Webb wrote “Galveston” especially for Campbell, but no. The singer told me the song was originally recorded by the Hawaiian nightclub entertainer Don Ho, and in fact you can find Ho’s version on YouTube. “Don Ho was doing a TV show with me,” Campbell recalled. “He gave me the record and said, ‘Here, I didn’t have any luck with this – maybe you’ll like it’.”

Ho’s version, sung in a style reminiscent of Perry Como, was much slower than Campbell’s, in line with Webb’s original intention. It also included different lyrics. Sitting in his Wellington hotel room, ignoring for the moment the golf tournament he’d been watching on TV, Campbell sang an exaggeratedly ponderous parody of Ho’s rendition, tapping out the beat in a dirge-like tempo.

Campbell’s up-tempo revision worked: “Galveston” stayed on the charts for 12 weeks in the US and was Campbell’s fourth-biggest hit, after “Rhinestone Cowboy” (1975), “Southern Nights” (1977) and “Wichita Lineman”. Though it’s more pop than country, a panel of experts convened by the Country Music Television channel to draw up a list of the 100 greatest country songs surprisingly ranked “Galveston” at No. 8. In a list that includes pure country classics such as “Stand by Your Man” (at No. 1), Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart” and Patsy Cline’s “I Fall to Pieces”, it looks out of place.

*

On the morning we leave Galveston, I strike up a conversation with the guest from the motel unit next door, who’s stowing his bags in a battered Ford pickup. He’s a hard-looking hombre: tall, lean and roughly dressed in black T-shirt and jeans, with dark glasses and a scraggy beard. He has a young pitbull terrier that he tells me he bought from a man who would otherwise have sold him to a Mexican who organises dogfights. Dogfighting, he says, is big business in Texas.

He comes from Odessa, in west Texas, and laughs quietly when I mention that I have a son in California. I tell him I have the impression other Americans dislike Californians, but he says it’s the other way around. Californians dislike Texans “because they’re so liberal and we’re so not”.

When I point out that California, like Texas, still has the death penalty, he responds with obvious pride that Texas executes more people than any other state. “Lots of states got capital punishment,” he says with a grin, “but this here’s the only state with an express lane.”

A Road Trip of American Songs (Bateman, $39.99) by Karl du Fresne is available at Unity Books.