AUT diet researcher George Henderson beholds the new weight-loss bible by 5:2 diet superstar Dr Michael Mosley – and declares it a triumph, with its “relaxed, considered, co-operative, mindful, repeatable, and hopefully enjoyable approach.”

Disclaimer: This is a review of a book that supplies strong medical advice about diet. If you’re interested in it but have a serious health condition, consult your primary care provider first, especially if you’re on blood sugar-lowering or blood pressure medication as the dosage may need to be changed within a relatively short time.

If you’d asked me about fasting a few years ago I’d have told you it was a terrible idea and that anyone who avoided food was barking mad. Anyone with any sense knew that snacking all the time was the way to stay healthy. Even if you fasted for a fund-raising stunt like the 48-Hour Famine, or to play Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “composition” Goldstaub (the score for which includes the instruction to “Live completely alone for four days without food” and not much else) it was expected that you’d eat sweets regularly and drink juice to “keep your blood sugar up”. (Hint: that’s not how it works. It’s surprisingly easy to keep blood sugar up, that’s how your ancestors survived countless 48-hour famines and why over 30% of Kiwis are diabetic or prediabetic).

In fact, when I got into this business seriously in 2012, the New Zealand Ministry of Health website still supplied advice for preventing type 2 diabetes that read, in part, “fill up on bread, pasta and rice”; that pdf has now disappeared without trace, but I don’t doubt its influence persists. As recently as 2016 the Ministry of Health came out swinging against low carb, paleo, and the 5:2 diet.

According to your government, the worst thing you can do is to stop eating for a while; the only thing worse is going paleo and eating too much real food. And thus the world continued on its merry path to type 2 diabetes and the metabolic mayhem that precedes it.

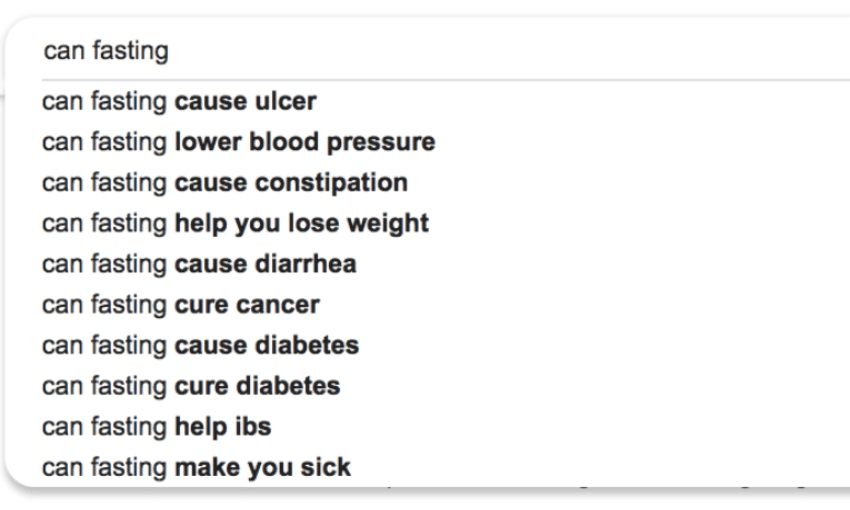

What changed this? More than anything, the internet did. Suddenly you could read enough scientific studies for free to eventually work out what they were really saying, if anything. You no longer needed to wait for some gatekeeper to pass on some half-digested, bias-coated finding or opinion without checking its plausibility (but if you like that kind of service, it’s still available in online news feeds and print media). You could argue with the people trying to tell you things in real time. Little by little, you could either profit by their patient explanations, or be enlightened by their propensity to obfuscate and pull rank. You could also share results and get support from ordinary people trying the same things you wanted to try. The internet, for all its sins, has been a game-changer for people trying to take back their health.

And one of these was our hero, Dr Michael Mosley, overweight and newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the disease that had killed his father.

Over the past few years, we’ve watched Mosley discover and promote the benefits of intermittent fasting. He not only invented the 5:2 diet, but saw it through to being rigorously tested and validated. Physician, heal thyself: Mosley has reversed his type 2 diabetes. That means he doesn’t have the disease anymore. His blood sugar and triglycerides (blood fats) stay in the normal range, without any medication, so long as he doesn’t eat crap. Some people say that isn’t a cure; but the corollary of that would be that eating crap isn’t a cause.

In his new best-seller The Fast 800 the good doctor describes how he put on weight and brought back his diabetes in order to test his revised diet plan – he just followed advice to “fill up on bread, pasta and rice”. It didn’t happen overnight, but it did happen.

In the not-so-distant past, you could look for a long time without finding a case of type 2 diabetes or heart disease in populations eating some very different diets – mostly potatoes and a little animal food in Ireland; mostly fish, meat and animal fat in the Arctic; and either mostly coconut, or mostly root vegetables, with meat and seafood, in the Pacific. The introduction of flour and sugar, and latterly refined oils, to those populations has always resulted, after a slight delay, in the advent of the “diseases of civilisation” – tooth decay, appendicitis, bowel cancer, coronary heart disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, gout and so on. We hear a lot about indigenous populations having a high incidence of genes for these conditions but, for 99% of cases, this only means that scientists are isolating the genetic variants that help to cause these conditions when modern, industrial-colonial food is available, and that did no harm before.

The Fast 800 updates Mosley’s earlier 5:2 plan, in that food intake on fast days, or during the rapid weight-loss phase, is increased from 600 to 800 calories. This amount is based on several trials carried out in the UK to test the “twin cycle hypothesis” of Dr Roy Taylor, in which rapid weight-loss on a 800 calorie-a-day diet (adequate protein, limited carbs and fats) reversed type 2 diabetes, long-term, in most subjects.

How much is 800 calories? Well, 10 eggs add up to around 780 calories. Four eggs with a little fat will keep me happy for half the day, which is starting to make the proposition sound more practical. Unless you need rapid weight loss for type 2 diabetes reversal, the 800-calorie diet in Mosley’s health plan is only used intermittently, together with a low-carb Mediterranean diet. It allows for regularly scheduled fast days where you aren’t, or shouldn’t be, starving.

The idea is that such a diet puts you into mild ketosis periodically, without needing to be as restrictive as the true ketogenic diet – a diet that rapidly lowers blood glucose, and also reverses type 2 diabetes if adhered to over a longer term. The Fast 800 explains how ketosis mildly blunts the appetite, and turns off the addictive aspects of eating, allowing caloric balance to be normalised more-or less spontaneously. Russell Wilder’s 1921 insight that dietary ketosis aligned with fasting (which was known to improve both diabetes and epilepsy) because fat would be used for fuel at the same rate is one of the few true “Eureka!” moments in nutrition science and deserves to be better known.

It’s obligatory, when reviewing a diet book, to try some of its suggestions and recipes. I made The Fast 800 hummus recipe, and it was easy and delicious. I fasted for 24 hours – with no food except a couple of long blacks with cream, maybe 80 calories all up, from one dinner to the next. This was easy – because it’s something I’ve done regularly ever since I worked behind the scenes on New Zealand’s own fasting bible, What The Fast!, put out last year by the authors of the popular What The Fat? diet book, Professor Grant Schofield, dietitian Caryn Zinn, and chef Craig Roger.

I’ve found that 24-hour intermittent fasting gets more and more comfortable every time I try it. One of the most striking effects of applying the various ideas in The Fast 800 and What The Fast! is that I can now go supermarket shopping without even noticing the aisles of brightly coloured rubbish. I can drive into the petrol station as often as I like and come away with nothing but petrol every time, year after year, and willpower has nothing to do with it.

Think about that. Think about it as a political statement about the capitalist consumerist society, if you like. Because, on the left-right political spectrum, a spectrum so densely populated with morons that anyone who can place themselves accurately on it needs their head examined, food choice is a powerful signifier of place. At one end, personal responsibility is the key to health. If you can’t choose wisely then you pay the price, say those who have never been to, or been awake in, the US where they put sugar and oil in the butter and cheese, sprinkle sugar on everything else, and if you ask for milk in your coffee you get a vial of white powder, and you really do not have a choice unless you’re wealthy enough to go somewhere special or patient enough to wait all day without eating.

*

Of course, any time anyone proposes a more effective way to control weight than simple moderation, a word I know how to spell but have never been able to define, we get the full-bore chorus: “Just eat less and move more; it’s all about calories innit?”

Imagine telling the beggar at the lights, “Mate, you just need to earn more and spend less.” Telling the poor to earn more and spend less is not only heartless, but also quite useless if you don’t explain, for example, that a loan with a high interest rate from the back of a truck will cost a lot more than a loan with a low interest rate from a reputable bank in the long run.

The carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis is exactly this kind of wisdom. Better people than me have tied themselves in knots trying to explain why it’s still Wrong, but I can only say that, in the entire history of Wrong Ideas, and humanity has seen some doozies, no Wrong Idea has ever helped as many people while causing as little harm as the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity.

Not that the focus on obesity is always relevant. We should care about the diseases associated with obesity and overweight; weight itself is only a crude marker for a process you will find in some underweight people if you know where to look. But if your own health has deteriorated as you’ve gained weight, then there’s nothing wrong with using your weight as a guide to improvement.

Mosley clears up some myths – rapid weight-loss early in a diet does in fact predict greater long-term weight loss, and, if weight is regained, some benefits of weight-loss persist. We’re not talking Biggest Loser style attempts to sweat weight off quickly in a storm of physical and emotional stress, but an altogether more relaxed, considered, co-operative, mindful, repeatable, and hopefully enjoyable approach.

High-carbohydrate diets for diabetes were introduced worldwide without any trial comparing them with the very low-carbohydrate diets that had previously been the standard of care, and have been proven inferior to them in every trial done since. For those of us interested in this question, Mosley’s appearance on Australian TV a few years back, when the head of the Australian Diabetes Association was asked to explain how their low-fat, high-carbohydrate, grain-based recommendations made sense, seemed like a tipping point.

Yet the pushback from an establishment that doesn’t want to admit mistakes can be relentless. Australian orthopaedic surgeon Gary Fettke recently faced disciplinary proceedings for “inappropriately reversing diabetes” in his patients rather than cutting off their feet. In New Zealand, the diabetic menu in most hospitals still includes cereal, toast, fruit juice, and a referral to the orthopaedic surgeon.

Yet there is hope. Mosley’s approach is gradually becoming mainstream medical advice in the UK; together with other pioneers like Professor Roy Taylor and Dr David Unwin, he’s managed to supply the evidence base needed for both fasting and low-carb, high-fat diets to become respectable options for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease.

His bedside manner, as it were, in The Fast 800 is perfect, skirting unnecessary controversy, compromising harmlessly, and keeping to the important point. Despite the lack of recipe pictures and diagrams, the large print and simple discussions will appeal to many. The Fast 800 exemplifies Einstein’s famous 1933 dictum: “Everything should be made as simple as possible but no simpler.”

The Fast 800 by Dr Michael Mosley (Simon & Schuster, $35) is available at Unity Books.