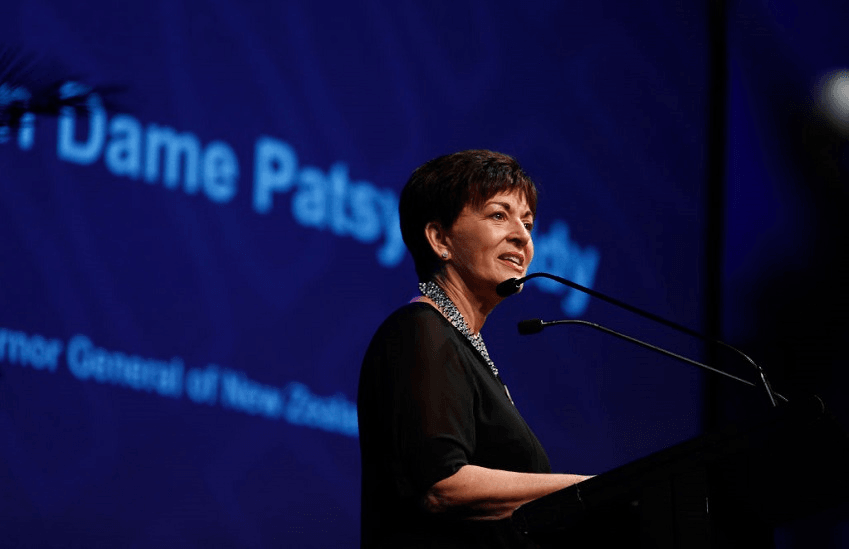

The NZ governor general, lawyer Dame Patsy Reddy, called out the “egregious” behaviour her generation endured from male colleagues in a powerful speech at the Women of Influence awards last night. Disruption, she said, is the only way to effect change

The 125th anniversary of suffrage in New Zealand is the ideal time to come together to celebrate mana wahine and wahine toa. To acknowledge the achievements of New Zealand women from all walks of life.

Kate Sheppard, and those who worked so hard to advance the cause of votes for women in this country, have long provided us with a great example of the power of influence. Speak up, organise, do the hard yards, form useful relationships with those who can help, and never give up. The suffragists, both female and male, wrote the book on how working together can influence powerful societal transformations.

It’s wonderful to see how much of an icon Kate Sheppard has become for New Zealanders. 125 years on from that ground breaking Electoral Act, she is a role model for anyone wishing to challenge the accepted order of things.

When I was growing up, Kate Sheppard had nothing like the universal name recognition she has now. In fact I was only dimly aware of her and her legacy when I first saw her image on our $10 note. It was a great pity, as strong female role models beyond teachers and nurses were rather thin on the ground when I was considering my career options.

There was the Queen. A fabulous role model in many ways but more of a fantasy figure. It’s tricky to aspire to being a Monarch when you live in New Zealand.

Later, when I was at university, there were activists like Germaine Greer and the New Zealand feminists of the 1970s who established the Women’s Electoral Lobby and reinforced the message that girls can do anything. They were simultaneously inspiring and a little frightening.

As thrilling as they were, as a young lawyer I found my role models were more closely aligned with the Establishment and my own working environment. Through necessity, not choice, most of my role models were men.

For today’s young women, the environment is different. There are female role models in every career choice and many older women to look up to and use as inspiration in their careers and personal lives.

For those of us who belong to these older generations, it’s our responsibility to encourage, advise and advocate for the young women of today.

Of course, just as women today can learn from the achievements of those who went before them, they can also learn from our mistakes.

Many of my generation felt that in order to succeed we had to be one of the boys or at least not make a fuss. That often meant ignoring some fairly egregious behaviour. That’s just how things were.

Were there other ways of doing things? Probably, but for many of us, it was hard enough getting permission to come aboard. We didn’t want to rock the boat, no matter how much the accepted order of things grated, or even adversely affected us. We were encouraged to keep our heads down and work quietly from within.

We thought things would change – it was just a matter of time. We now know that we were wrong – or at least too optimistic. It seems that for culture change to occur at anything faster than a glacial pace, disruption is inevitable.

It is challenging to speak truth to power. I applaud the strength and courage of those who have recently spoken up to expose toxic workplace cultures. I hope those actions spur real change. If not, I encourage you to keep speaking up. If we keep quiet and do nothing, nothing changes.

The suffragists of the 1890s didn’t keep quiet. Three times they took petitions to parliament, each one bigger than the last. The “monster” petition of 1893, fastened together with flour and water paste and rolled around a broom handle in Kate Sheppard’s kitchen, remains one of the largest examples of influencing in our history.

The 32,000 signatures represented one quarter of the female population of New Zealand – the equivalent of over half a million women in 2018 terms. Imagine having that level of support for an issue that directly affects women today – we could move mountains!

We’ve come a long way since 1893 but there are still areas of concern. The gender pay gap, the lack of female representation on boards, unconscious bias, moral licensing, harassment and micro-aggressions in the workplace and inflexible work hours are just a few of the issues that continue to affect women.

My challenge to you, as women of influence, is to use your influence to change whatever it is that is stopping us achieve true gender equity. By doing so, we will make a better New Zealand for ourselves and others.

Kate Sheppard would approve.

Kia ora huihui tātou katoa.

Dame Patsy Reddy gave this speech at the Women of Influence Awards in Auckland last night.